An Intimate Portrait of a Coronavirus

Biologist David Goodsell Uses Watercolors to Explore Viruses and Cells Molecule by Molecule

Humans have probably always known about what viruses can do: throughout the ages, people have endured the familiar sniffles of a cold, the tell-tale rashes of measles, the occasional devastation of brand-new illnesses like today’s COVID-19.

But scientists didn’t have a hint of the true nature of viruses until 1892, when a Russian botanist realized tobacco plants were getting sick because of an unknown, invisible, and incredibly tiny pathogen—something far smaller, even, than bacteria.

Even today, with advanced microscopes and imaging technologies at researchers’ fingertips, it remains nearly impossible to “see” viruses in the lab. Which is why biologist David S. Goodsell started making watercolor paintings of them instead.

Goodsell, a computational biologist at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California and the RCSB Protein Data Bank, came of age as a researcher during the 1980s, trying to decipher the shapes of proteins and DNA. He wanted to be able to visualize the detail of what was going on within the cells he was studying, too—but computers weren’t yet powerful enough to synthesize what was known about the chemistry of individual proteins and the larger structures of cells. It was impossible, in the lab, to create a graphical “vision of what the whole thing looks like,” he says.

But Goodsell thought such a thing might be possible with low-tech tools. His grandfather had taught him to paint watercolors—”traditional scenes of barns and trees”—when he was young. If imaging technologies couldn’t produce a picture of the biology Goodsell wanted to visualize, perhaps he could do it himself, with some imagination and a brush.

Thus Goodsell’s “Molecular Landscapes” were born. Surveying scientific papers that described viruses and the proteins within them—sometimes with images and other times with data from DNA sequences and atomic structures—he began assembling mental images of the things he worked on.

Goodsell’s first paintings depicted DNA. The lab he worked in was trying to develop an anti-cancer medication that would bind to the molecule’s double helix. Goodsell hoped that painting what DNA’s tiniest nooks and crannies looked like close up might help with the drug design.

As Goodsell’s research focus evolved, he began painting viruses.

Viruses are made up of bits of genetic material—strands of RNA or DNA—organized by proteins. Whether viruses are alive or not depends on how you define “living.” Viruses don’t have the cellular machinery to fuel respiration or metabolism, but still they reproduce—even if they only succeed by working their way into a host cell and using its resources to find new cells to infect. Viruses can’t move on their own, relying instead on a sneeze, a kiss, or a vector, like a mosquito to spread and multiply.

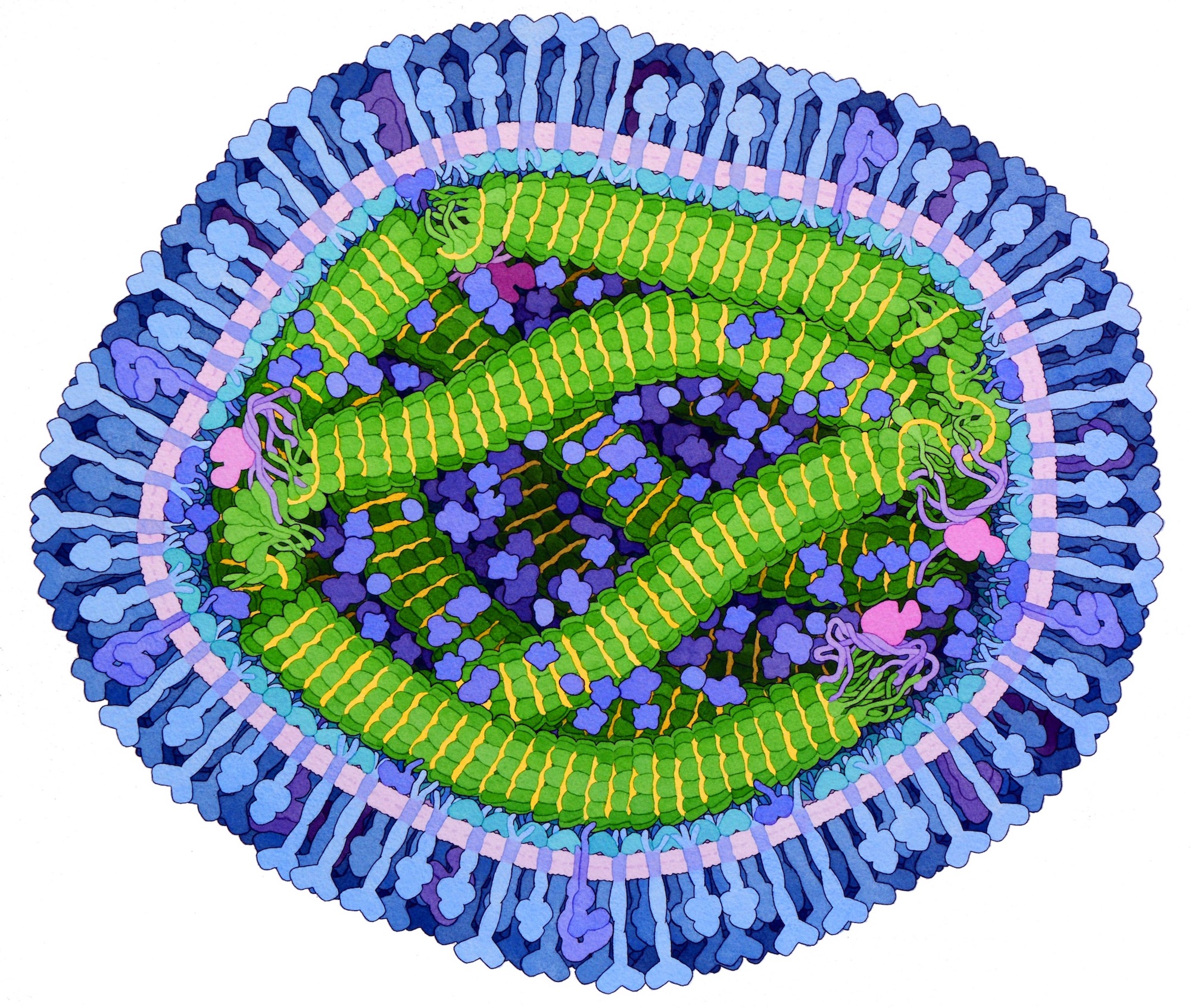

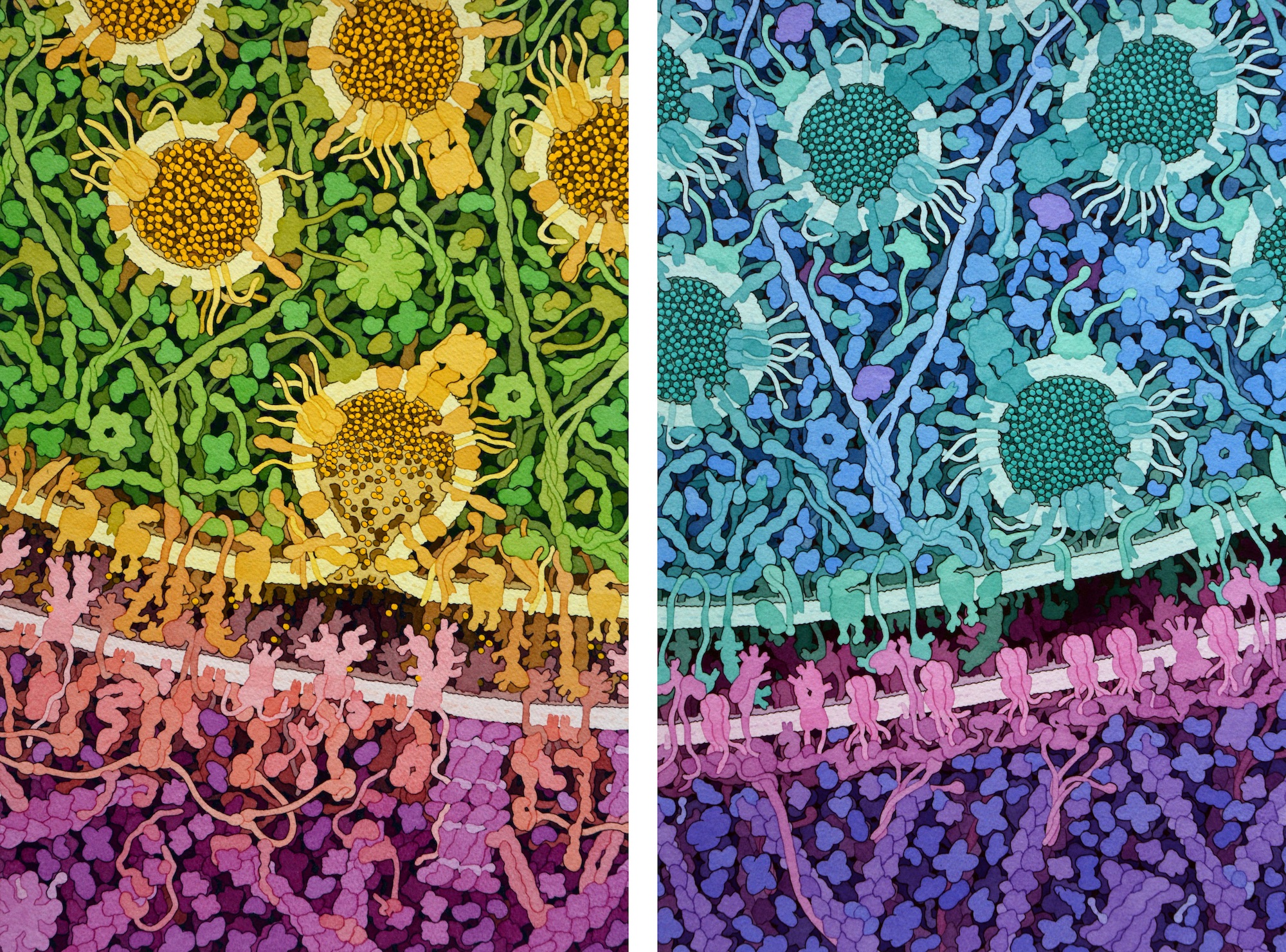

When Goodsell started studying HIV, the retrovirus that causes AIDS, he also began painting it. Since then he has created about a dozen HIV watercolors, updating the images as science improved our understanding of the virus’s biology. In Goodsell’s early HIV paintings he depicted the outside of the virus as if it were studded with protruding proteins. Now that journal articles report that HIV actually has very few of these proteins attached to it, he paints the structures in a patchier configuration.

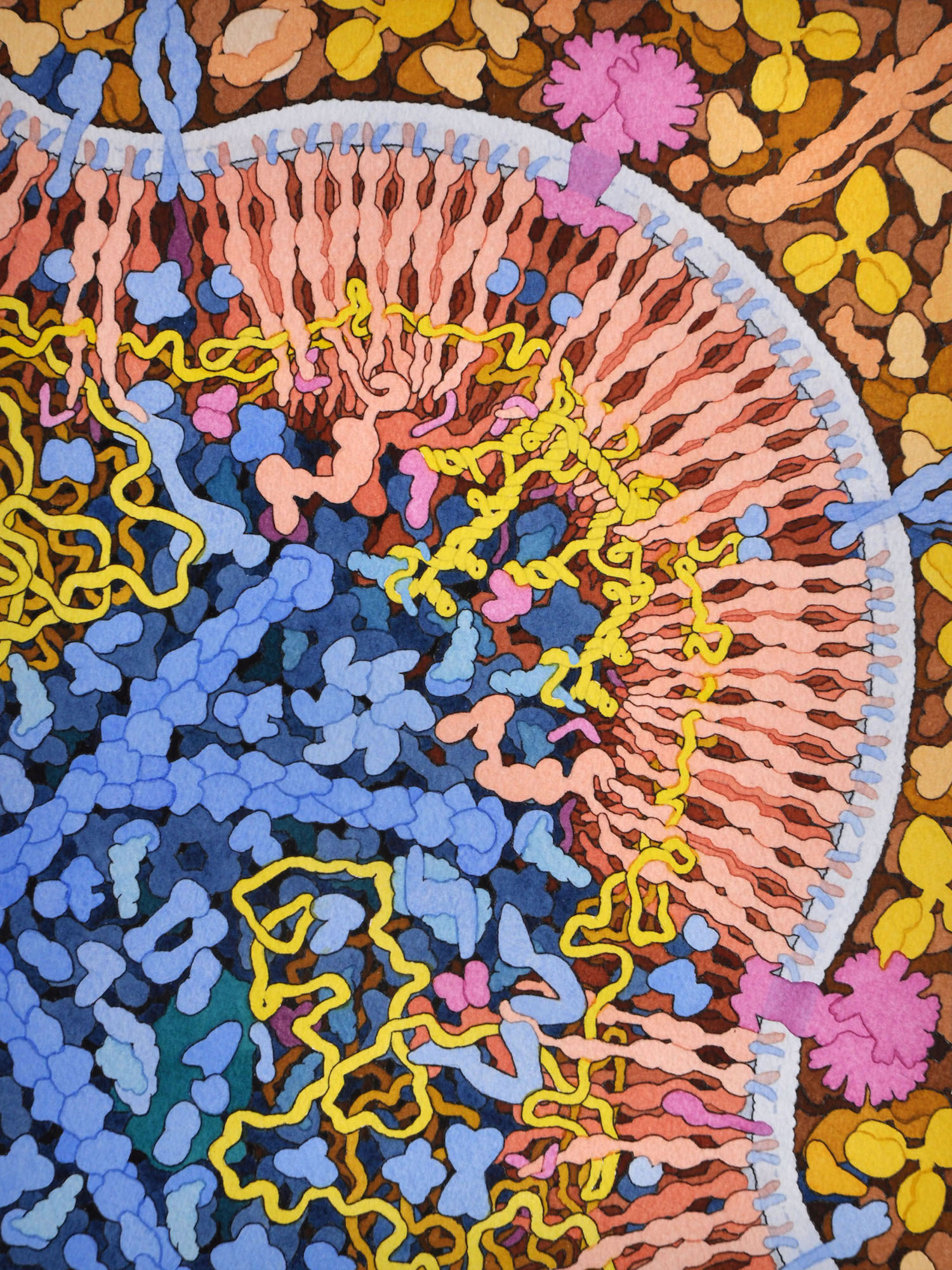

In his paintings, Goodsell always strikes a careful balance between remaining faithful to the data and “taking artistic license when things are less well characterized.” When he painted the Zika virus in 2016, Goodsell couldn’t find much information on the cells that Zika targets for infection, so instead the painting depicts an immune system cell.

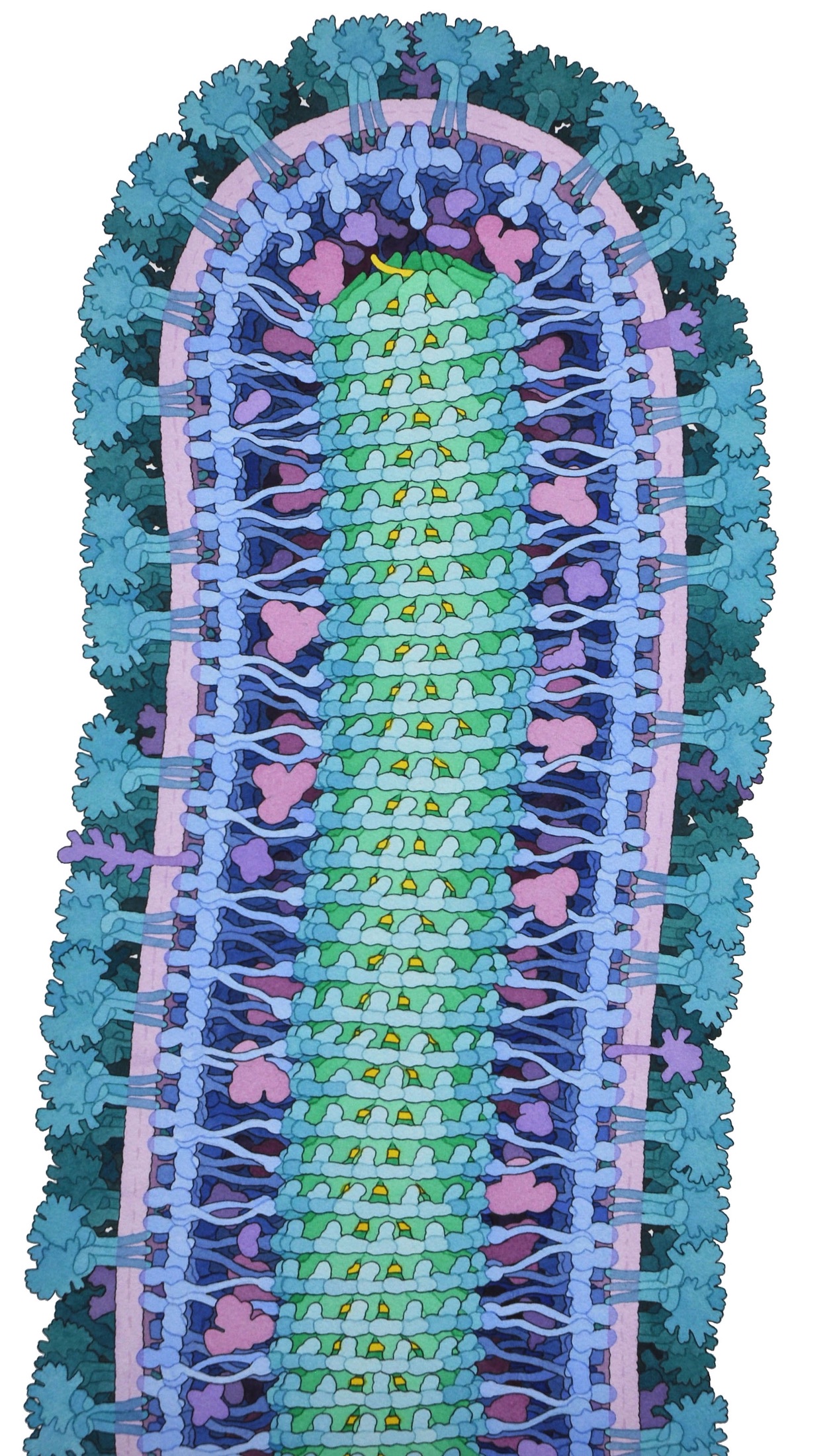

Similarly, in 2014, he completed a painting of Ebola at a moment when a lot was known about the virus proteins but almost nothing was known about the connections between them. “I had to work things out based on the size,” he muses. “Maybe they know more about it now.”

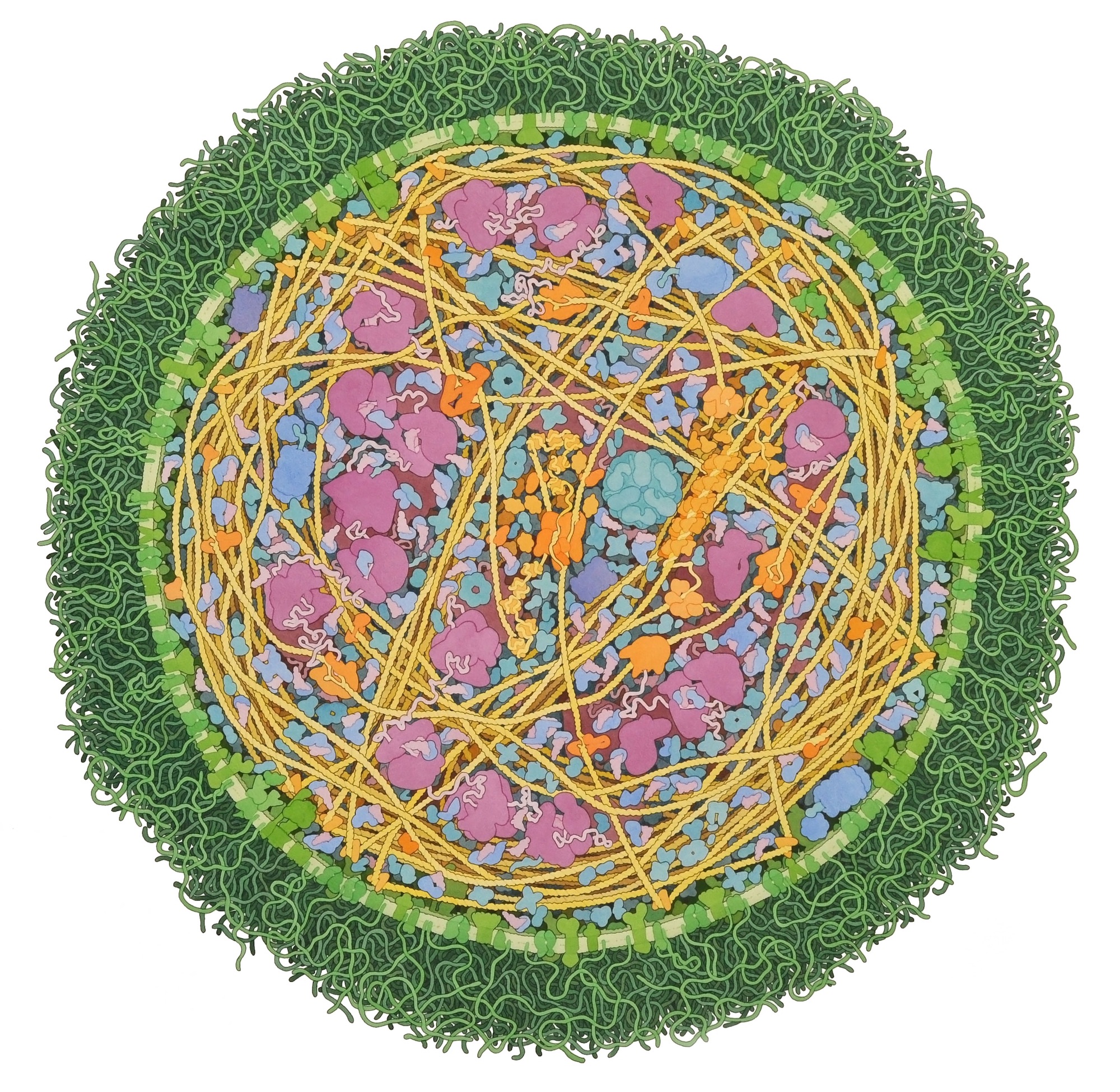

Goodsell often chooses subjects from the headlines. His new coronavirus painting, inspired by the COVID-19 epidemic, is in fact a depiction of the SARS coronavirus that emerged in China in 2002, causing respiratory disease in more than 8,000 people and eventually killing 774. There are many types of coronaviruses—some of which mainly infect birds, others that are common in mammals such as humans. Many cause no illness at all. Some bring on minor woes like the common cold.

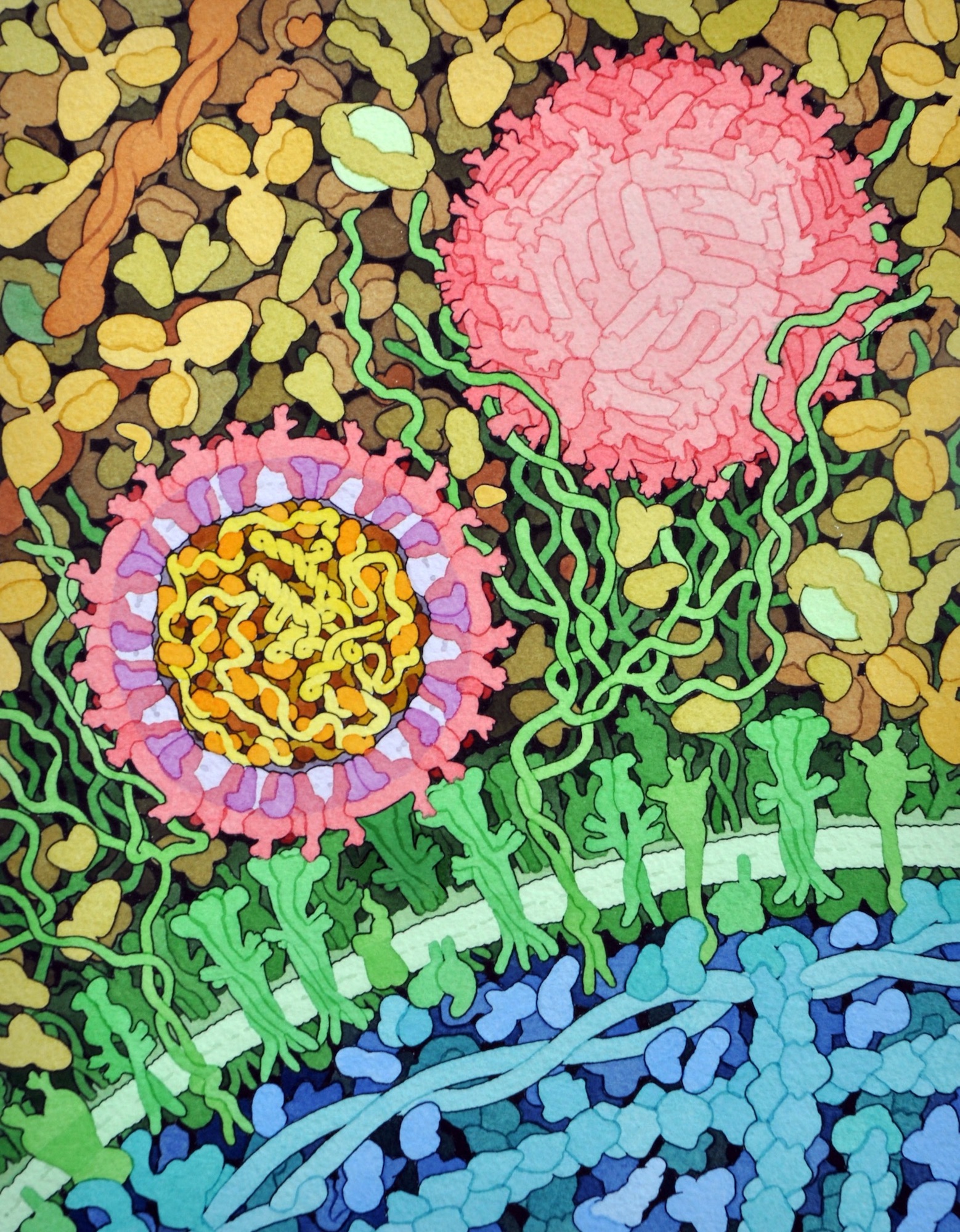

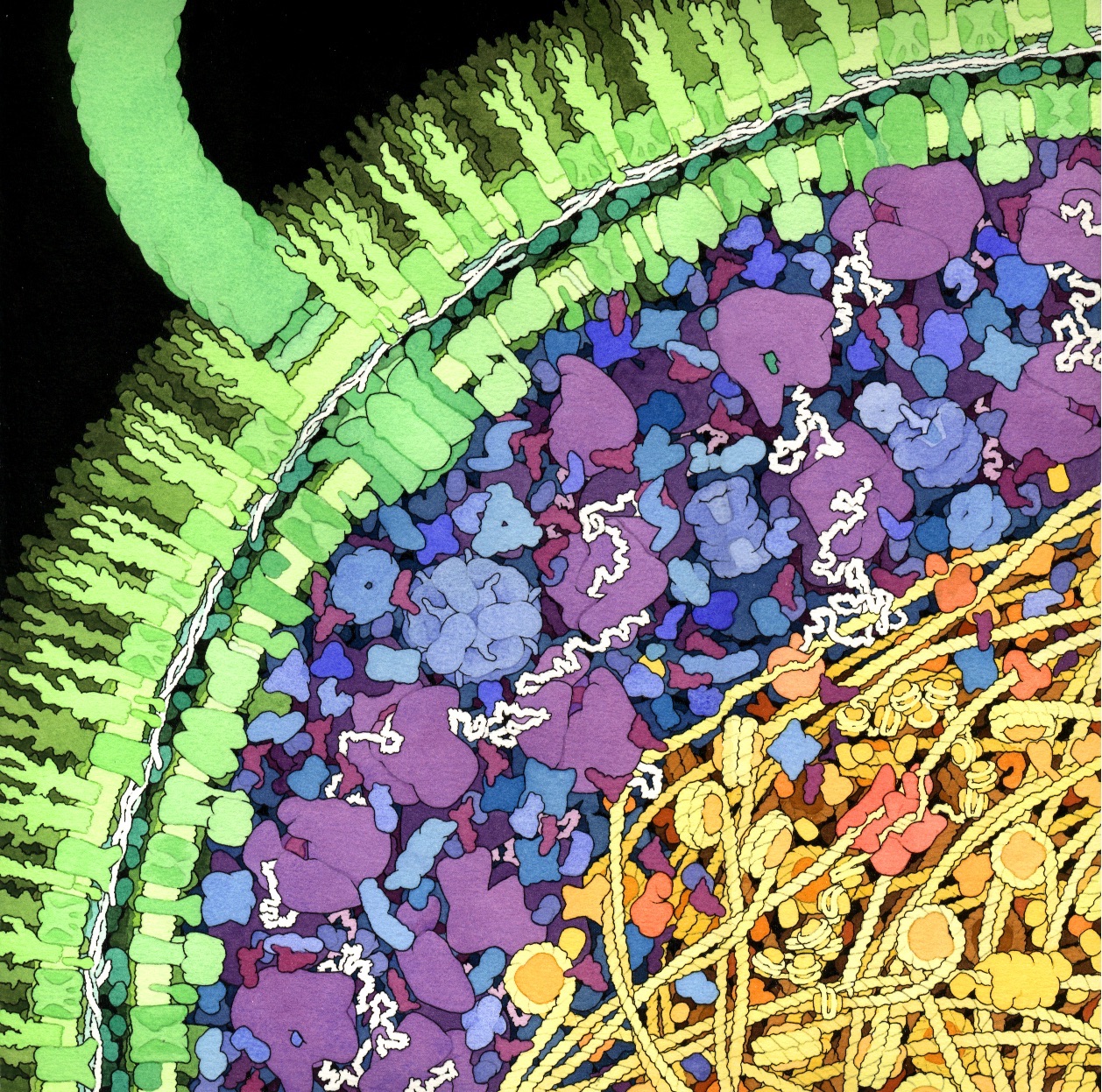

Goodsell found electron microscope images of the entire SARS virus, which is surrounded by a ring of so-called “spike proteins”—“very pretty … like a little crown”—that help the virus attach to and enter the cells it targets. (These “spike proteins” also inspire the coronavirus’s name: “corona” means “crown.”) He was able to find data that explained the protein structure of the spike proteins but had to imagine what the membrane protein that reorganizes the DNA inside the cell might look like. His painting captures the moment when a coronavirus is breathed into the respiratory tract, not yet attached to a cell. The greenish curlicues around it are mucus; little yellow “Y”s are antibodies.

Computers today are far more advanced than what Goodsell had to work with in the 1980s. For the last five years or so, scientists have had machines that let them generate images of viruses and the like, integrating information from multiple sources without an artist’s brain mediating the mix.

Goodsell welcomes the advances—and plans to continue painting. His next series will depict vaccines, including poliovirus as it is neutralized and a recombinant influenza vaccine. The pieces will debut at a show in Wichita later this year.

Send A Letter To the Editors