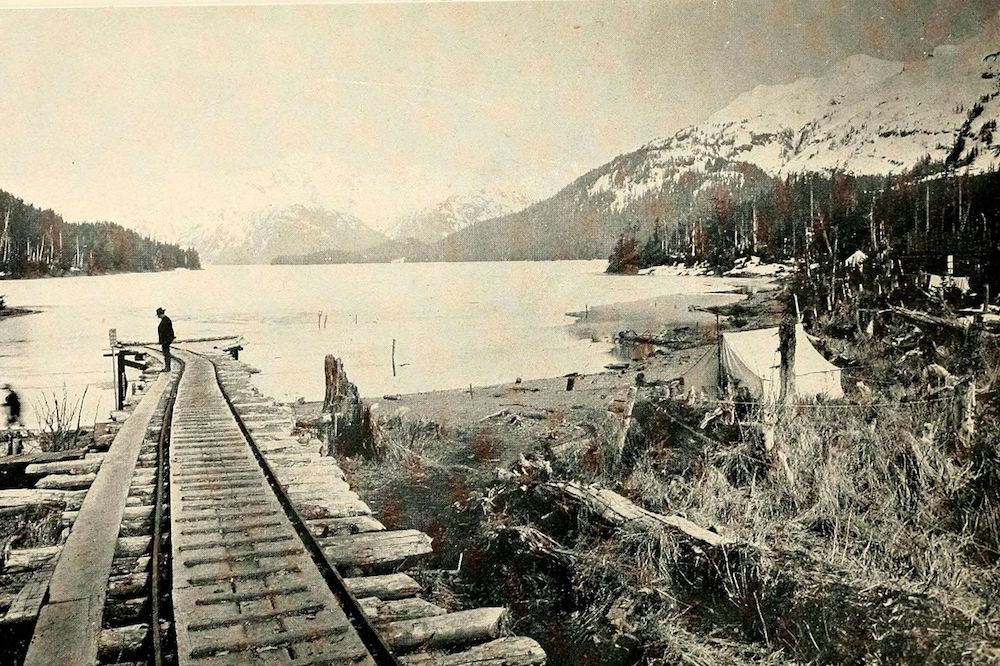

Railroad construction at Eyak Lake near Cordova, Alaska, 1908. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Alaska officially became a state in 1959, but its modern origins occurred in the two decades that followed the discovery of gold in the Klondike in 1896.

At the turn of the century with reports of innumerable mineral resources and a limitless agricultural potential surfacing, this little-known U.S. possession suddenly grabbed the world’s attention. As pioneers and settlers rushed into the frontier and returned during this period, Alaskans founded many of today’s cities (including the two largest, Anchorage and Fairbanks), birthed a structure of highway and railroad transportation, and established a judicial system and a rudimentary form of self-government, which led to statehood a half-century later.

All this activity took place during the Progressive Age in American politics. It was a time of social and economic reform, when Congress and federal agencies recognized the need to regulate large corporate trusts, manage extraction of natural resources, ensure some level of fairness for consumers and workers, and build much-needed infrastructure projects. At the heart of the Progressive movement was the conviction that a strong federal government could be the agent of change, because government was the only entity with power sufficient to produce broad reforms.

The swelling Alaska population benefited from the Progressive movement in a number of ways. By 1900, Congress had enacted criminal and civil codes and appointed judges to serve each of the Alaska territory’s three newly established judicial districts. In 1906, a new federal law allowed Alaska residents to elect a delegate to represent them in the U.S. House of Representatives. And in 1912, Congress responded to Alaskans’ demands for self-government by creating an elected territorial legislature.

But the greatest of all Progressive Age accomplishments for Alaska was passage of the Alaska Railroad Act in 1914.

The act provided $35 million to build and operate a railroad from an unspecified tidewater port into the Alaskan interior. President Woodrow Wilson viewed Alaska as a storehouse that should be unlocked, and a railroad was, in his words, the means of “thrusting in the key to the storehouse and throwing back the lock and opening the door.”

It was significant that it was the federal government, and not private sector enterprise, that did this job. At the time Railroad Act passed, Progressives nationwide were at war with the monopolizing power of corporate trusts.

In Alaska, two of the biggest business entities in the world had combined to form an enterprise that controlled nearly every sector of the economy. The Morgan-Guggenheim Alaska Syndicate, owned by New York financier J. P. Morgan along with the international Guggenheim mining company, dominated the mineral extraction and transportation infrastructure in most of the territory. The syndicate sent teams of lobbyists to Washington to block efforts to build a government railroad, which would interfere with its monopoly on transportation. The syndicate was—as James Wickersham, Alaska’s non-voting delegate to Congress, described it—the “overshadowing evil” that darkened the prospects of every struggling pioneer in the new and developing territory.

“Which shall it be?” Wickersham thundered from the floor of the US House of Representatives in arguing for the Alaska Railroad Act. “Shall the government or the Guggenheims control Alaska?”

The answer from a Progressive-minded Congress and White House was clear: it would not be the Guggenheims.

Never before in the history of the westward movement of Americans had Congress stepped in to build a transportation system where private enterprise could likely have provided comparable service. Moreover, the railroad was quite explicitly an expression of the country’s anti-trust, anti-monopoly mood.

Progressives saw Alaska as a wide-open place where their ideals could be put into practice, a model of the democracy they wanted. It would open vast areas of mineral and agricultural wealth, creating jobs and opportunities for the working public; it would demonstrate the Progressive conviction that government at its best was an agent for progress and improvement in people’s lives; and it would make a statement of the strength of federal regulatory control in the era of popular reaction against the workings of corporate trusts. It would operate in a place where the giant Alaska Syndicate threatened to monopolize every sector of the economy.

Of course, Progressive-age politics was not the singular reason why Alaska was developed. The opportunities to be had in this northern frontier were exciting enough on their own to attract multitudes of pioneers, settlers, and entrepreneurs. Infrastructure would surely have been built even without the benefits of Progressivism’s considerable influence.

Alaskans were not always happy about the federal government’s investment—or lack thereof. During the Progressive Era they complained endlessly about what they perceived as neglect and ill-treatment at the hands of the federal government. “Think of it!” a Skagway newspaper cried in 1906. “Here we are a people denied the right of self-government, taxed without representation.” The editor concluded that Alaska lived under “a system compared with which the government of the American colonies under George III was broad and liberal.”

Alaskans in that moment had good reasons for their outrage: The territory’s vast coal deposits remained off-limits to mining, and hundreds of workers sat idle for eight years starting in 1906 as Congress failed to pass legislation providing for a fair leasing system on federal coal lands. This was only one example of government delays and red tape that infuriated residents of the North.

Such treatment led Alaskans to feelings of abuse and what amounted to a split personality in regard to their relationship with the federal government. They decried the lack of assistance where they saw a need while at the same time they wanted the government off their backs, leaving them free to develop the resources without interference.

Federal help did come to Alaska, but it arrived piecemeal over the course of decades. Over time, the government responded with many projects and benefits that enriched Alaska. These included highways, national parks, systems of public education and health care, and military bases, to name just a few. From today’s point of view, we can see that Alaska as a territory and a state has been enriched far more than neglected or abused by the federal government.

By 1916, Progressivism had run its course, though in its 20 years of life it had accomplished much in the way of social, political, and economic reform. Its legacy includes antitrust legislation, regulation of interstate commerce, child labor laws, direct election of U.S. senators, conservation of natural resources, and a movement toward women’s suffrage. The forces underlying all these advances were a commitment to the rights of the masses and a belief in the power of the federal government to effect change.

Send A Letter To the Editors