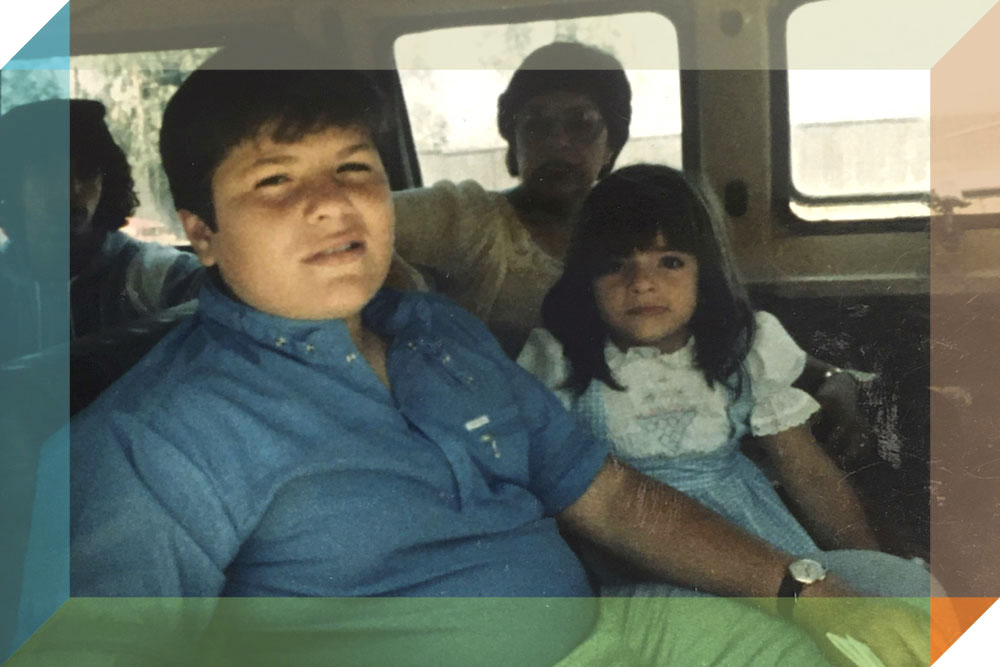

Writer Oscar Villalon, pictured with his family circa middle school. Courtesy of the author.

I haven’t brought my wife or son to see where I mostly grew up. I keep meaning to. But even though it’s less than a mile from my father’s condo in Rancho Peñasquitos in northern San Diego County, the gulf between that place and the apartment I grew up in the ’70s and the ‘80s seems to spread beyond the horizon, a distance only traversable by me, and only in my memory.

Maybe that’s why more and more I find myself, as I wash the dishes or fold my son’s clothes, returning to scenes and impressions of where I once lived, trying to understand the distances of time, decoding a narrative that originates from there.

It took my parents 15 years to move about a mile from the old place. In the early ‘90s, just as I started working at a newspaper in Los Angeles, they left the three-bedroom apartment in Penasquitos Gardens where seven of us had lived for a two-bedroom, one-bathroom townhouse condo where only four of us would now be: my mother and father, and my two youngest sisters.

I rarely visited them in the new place. I worked constantly at the newspaper, through every holiday, and found myself at the condo only on special occasions, such as when family from Mexico was staying there during a vacation to the States. And when I went to work for a newspaper in San Francisco around 1995, my visits became even more infrequent. It wasn’t until my mother was diagnosed with Stage IV cancer that I started spending more time at the townhouse, flying down from SFO as often I could, trying to be as present as possible. After my mother’s death in 2001, and especially after I got married and then had a son, the visits ramped up, to at least three times a year.

When we go to visit my father, who lives alone in the condo now, we can look up from the sidewalk of the nearby four-lane road and see the fencing around my old elementary school. Across the street from the school, running up the hill, are squat beige blocks of apartments.

As if in a lucid dream, I let myself wander deep into those buildings, all of it low-income housing when I was there. I go up the slope past the park with the asphalt basketball court, past the cinder block housing for the two metal dumpsters where we tossed our trash, and past the windowless low-ceilinged laundromat evocative of a holding cell, and then go left along a dirty concrete pathway, to the place where we lived—that bottom-floor apartment, a few cardboard boxes stacked in the corner of its patio rarely used except for the one or two times my father, angered for reasons lost to me now, kicked my brother and me out there to sleep, until somebody tugged open the sliding glass door to let us back in. Once I sat in a kitchen chair there, taking my turn for my mother’s friend to cut our hair. I closed my eyes as she snipped around my ears. I listened contentedly to her and my mother talk about things I cannot recall.

The physical place would tell my wife and son nothing. They would just see a bland apartment block; it would require pointing out what can’t be seen, apparitions that would only mean something to a very few.

There was the white neighbor who got shot in the back as she kneeled in her living room in front of a balance scale, weighing the pot for the man who arrived at her door carrying a briefcase, ready to buy her product, but drawing a gun instead. In her back bedroom, two toddlers she was babysitting went on napping. She came by our place later in her new wheelchair to tell my mother what happened, beaming because though she couldn’t walk anymore she had finally found the Lord.

Or there was the boy from one of the many other Mexican families in our knot of buildings, who always elicited a withering look from my dad, because he was a kid who was obviously heading for trouble, as the songs say. He wrecked a car he was driving after partying and was left brain damaged. His sister had to escort him around, his head lolling to the side, an unreadable smile on his placid face.

We would go quiet whenever they walked by. Nobody ever said, I’m sorry, or How are you doing? The sister’s flat eyes filled us with dread and resignation; this is how you can end up, it was understood.

Everybody worked hourly, if they had a job at all. Kids were alone, unsupervised once they were out of school, because their parents were at work, night and day, or their parents were just somewhere else. We would stay out late, shooting basketball or playing two-hand touch football until it got too dark to see what we were doing. One night, when the darkness forced us to stop playing, an older kid got us to run a bunch of drills in the park: pushups, wind sprints, crawling on our bellies across the grass, whatever came to his mind. What the Gardens needed was a gang, he said; we needed to form up. This didn’t seem at all unreasonable. But the longer we drilled, the more fierce he became, until he seemed to be only talking to himself, envisioning a greatness that only he could behold. We begged him to let us go home or we’d be in trouble, and he relented, but we were to come back to this part of the park again tomorrow night. We were going to be bad-ass, we were going to be some real motherfuckers.

Nobody went back, but he followed his vision to some degree, eventually joining a gang many miles to the south of us.

Years later, he was in another neighborhood, pushing open the window to a stranger’s house, his leg hooked over the sill, when he caught a shotgun blast to the chest. That’s how it was told to us, anyway. He never came around again, though all the proof we needed to know it was true was the inconsolability of his baby cousin (a slender, curly-haired boy who tried to become as hard as his dead primo, though nobody took him seriously).

I find it poignant if distressing that among all the kids he was the only one who ever articulated an ambition, declared a desire that wasn’t limited to where we wish we could go eat or who we’d want to fuck or what car we’d want to buy if we could have afforded it.

But you don’t make plans, not in the Gardens, anyway. You just see what openings life affords you and you take them. And those decisions, like tributaries off a wide and mysterious river, paths that will take you who knows where, aren’t really choices. They’re just what happens to be available. Open the door, or not. It may make no difference, or it might mean everything. Like the man said, things happen to you.

I find it a small miracle I am where I am. I picked the right waters to follow, or if not the right ones, the ones that led to more streams, more options. But I had no idea what I was doing, beyond knowing I couldn’t stay in the Gardens.

Like everybody there looking to get out, I was working without a compass, taking guesses. Whenever I despair at what could be considered the shortcomings of my life—still renting an apartment, not much money in the bank, opportunities never seized because of obliviousness or ignorance or simply marginalization—I think of when we lived in the Gardens. My life could’ve been mean, my joys minimal, if at all.

I have done, I think, all that I could to improve the lot that was given me, and I should take comfort in that. But I’m also aware this is a line we all must believe.

There are one or two families that I knew as a kid still living in the Gardens, or so I’m told. People who have abided. I think of them sometimes, and wonder if they remember those of us who left. Do they also tell themselves that things could’ve been much worse? Can we respect that they did all they could, too?

Send A Letter To the Editors