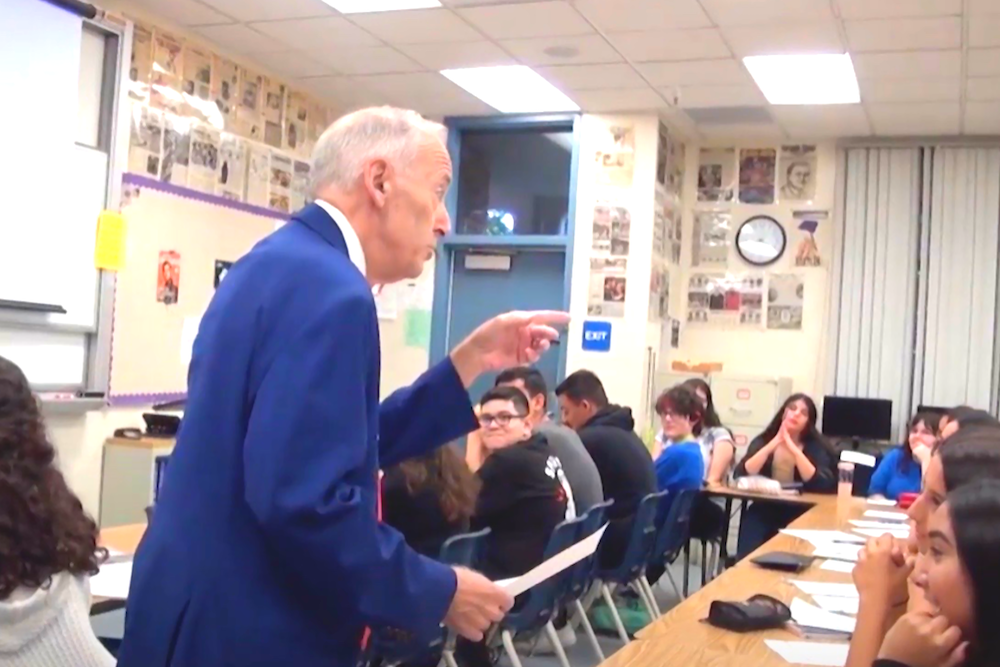

After three decades at Hoover High School, veteran teacher Brian Crosby reflects on his final days on the job, teaching remotely in COVID. Courtesy of Brian Crosby.

“Have a good spring break!”

Who knew that those words would be the last I would ever say to my students in a classroom?

After that final class on Friday, March 13, my high school in Glendale, like other schools, would close and never reopen. We would finish out the Spring, 11 weeks of it, via distance learning.

That meant no graduation ceremonies for seniors. And for me—another type of senior, 55 work days shy of retiring from teaching—that meant no retirement parties, and no celebratory moments of saying final goodbyes to colleagues and students. All of it deleted before it could materialize. A black hole.

I had no time for self-pity in March because I quickly had to re-learn how to teach, now in a virtual classroom environment. I had been teaching English and journalism at Herbert Hoover High School in Glendale since 1989 in a traditional classroom setting, and now I was about to embark on a journey I didn’t know I was going to take.

And neither did school officials who were unprepared for such a moment. They were scrambling to train teachers on online platforms, while distributing laptops and Wi-Fi hot spots to students who needed them—all in a week’s time.

I found it terrifying yet thrilling and after viewing a few webinars that the district provided, I got excited. Not so much about the tools themselves, but the fact that the district allowed teachers to choose how to teach and which tools to use.

It was something I had never experienced before in my 31 years of teaching—the district entrusting teachers with selecting the best way to teach, not mandating one method for all.

During the school year I taught five classes: four advanced 10th grade English and one journalism. Using Google Classroom, I consolidated the four English classes into one for easier workflow management. Why upload the same lesson four times in four different “classrooms”?

Knowing that the very first day of distance learning would feel foreign, I wanted to soothe my students’ nerves with a video of me talking directly to them, reprising a song I sang to them on the very first day of the school year back in August.

My inspiration was Fred Rogers. Instead of rules, we discuss expectations. Instead of penalties, we discuss rewards. Instead of a classroom, we have a neighborhood.

I sang “It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” with altered lyrics such as “it’s a beautiful day in this classroom now.”

With Mr. Crosby’s Neighborhood premiering on March 30, I would sing it again on video, for this would be the second First Day of the school year.

Once students viewed the video, dozens emailed me about how much they liked it, that it gave them comfort at a time when they were troubled with what was going on in the world.

The reaction motivated me to create more videos, and I couldn’t wait to pursue this new form of teaching which allowed my creativity to flourish.

And then reality settled in.

Distance learning was exactly like its name: distant.

While most of my English students submitted work and responded to my emails, one-third of my journalism staff disappeared. No submissions, no responses, no pulse, as if they were suddenly in a witness protection program. Struggling students no longer fall through the cracks; they have found an online hiding place, never to resurface.

What’s more, Google Meet and Zoom are not substitutes for in-person teaching. Classroom discussions, literature tests, and group projects could not be replicated online. There was no way for a teacher to know with certainty if the work done by the student was original, performed without the assistance of any person or source.

How could I give students a test? I couldn’t. Students could share responses.

How could I assign students an essay? I couldn’t. Most of the papers students write for me are done in class to ensure their veracity. Not now.

Courtesy of Brian Crosby.

Even ordinary lessons normally completed neatly within one class period drag on for a whole week; it’s like working in slow-motion.

For example, here is how a lesson from my Holocaust unit would play out in a regular classroom. Usually I show students a video of Auschwitz survivor Kitty Hart-Moxon returning to the concentration camp. For 47 painful minutes, she describes in excruciating detail the horror of what she experienced.

Before I show the video, I share her biography so they have familiarity with her background. Then I pass out a viewing guide that focuses on significant moments of the video.

I project the video onto a large screen with Bose speakers, an immersive moviegoing experience that all 34 students share collectively.

Midway through I pause the video and have them pair up with a partner and discuss answers to the questions. We then have a whole class discussion. After that, we review the next set of questions and resume the video.

By the end of day two, the lesson concludes with a short piece of writing in which students reflect on the video and make connections to Elie Wiesel’s Night, the memoir they just finished reading.

Compare this to the virtual classroom version of the same lesson.

On Monday, I post the notes, video and questions all at once, giving them two days to complete the assignment. Students are on their own to read the materials and watch the video.

There is no way for me to know if students are reading the material or watching the video. A teacher in the online environment has to proceed with an abundance of faith.

I cannot control when they do this or the speed at which they do this. Viewing the film on a laptop or cell phone in the comfort of a student’s home diminishes the impact, with the students starting and stopping the video as they please. It is no longer the emotional experience they would have had in my classroom.

Wednesday, I review all 112 student answers to the 16 questions. In person, we would have spent 10 minutes for students to share with a partner, then 10 minutes of sharing with the whole class, thus completing the task. Now, I have to actually read 112 written responses and select parts of them to share with students so they can broaden their perspective by hearing from their peers. The result: the whole thing takes too long and is lifeless.

Thursday, I post those select responses and ask students to comment on them to emulate conversation.

Again, in a classroom, this give-and-take would have energy, excitement, emotions running high, maybe erupt into an informal debate—a lesson impossible to orchestrate online.

Friday, I finally post their comments on what their peers had to say.

Online, the lesson dissolves into a lackluster exercise.

Within two weeks of teaching this way, I realized that the main ingredient missing was live performance. When students and teachers congregate in a classroom, together they give life to a lesson. Without sharing the physical space, that energy is unplugged. An electric group learning experience disintegrates into a dim “do your own thing” keyboard task. We all end up working alone in the dark.

Teaching in isolation from a laptop via distance learning was not the job that I had grown to love over three decades.

If I had any urge to change my mind and come back to work another year, distance learning confirmed that I had made the right choice. Schools will not be normal come August, most likely returning with a hybrid of in-class and virtual time.

That’s not for me.

I’m lucky in a way that this happened to me now when I was already on my way out. I feel for my colleagues who remain. It’s not going to be fun.

Send A Letter To the Editors