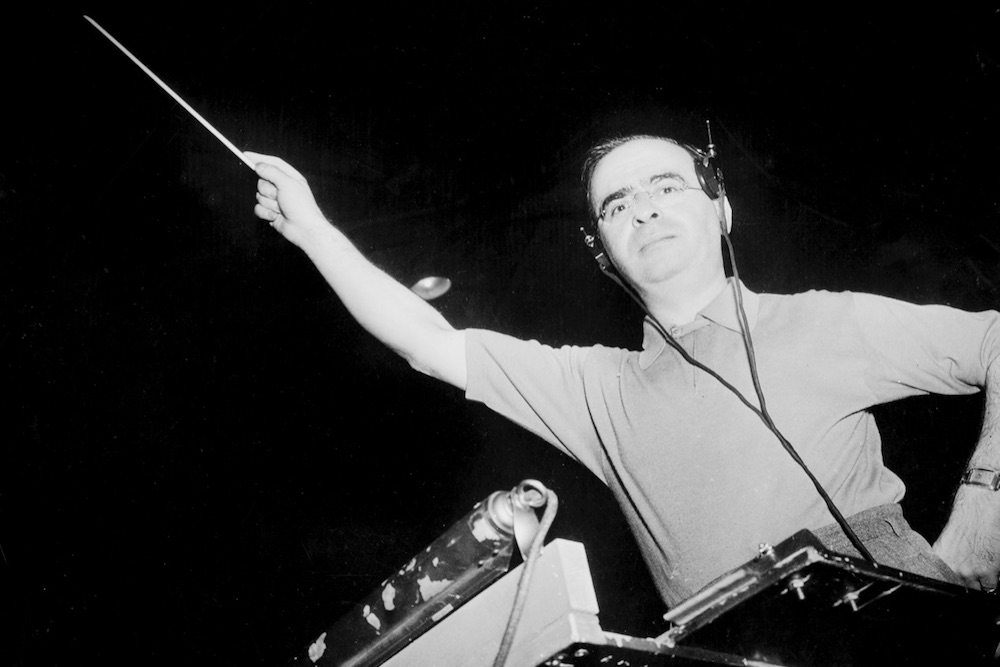

Max Steiner conducts his score for Gone with the Wind (1939). Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University Library, Provo, Utah.

An international crisis triggers record unemployment. Hollywood bleeds red as movie theaters shutter. And one major studio faces imminent closure, putting all its hopes on a would-be blockbuster.

The year is 1933. The studio is RKO. And the movie is King Kong.

Then as now, audiences made anxious by global upheaval hungered for escapism; and in March 1933, Kong delivered the financial rescue its makers prayed for. But the movie might have failed, depriving us of later RKO classics like Citizen Kane, if not for the ninth-inning involvement of one man: RKO’s 44-year-old music director, Max Steiner.

You may not know the name, but you do know his music. More than any other composer, the Vienna-born Steiner established the ground rules of writing movie music that are still in use today.

Pre-Steiner, orchestral underscore was rare in talking pictures, which replaced silent films in 1929. As King Kong neared completion, nervous RKO brass told Steiner not to waste additional dollars writing music for the film, after finding the ape’s stop-motion movement underwhelming.

But Kong’s visionary producer, Merian C. Cooper, knew better. As Steiner recalled, “Cooper said to me, ‘Maxie, go ahead and score the picture to the best of your ability. And don’t worry about the cost because I will pay for the orchestra.’”

Steiner’s epic score—a thrilling synthesis of Wagnerian opera, Stravinskian dissonance and Viennese romanticism—convinced audiences that Kong was both terrifying and ultimately tragic. Its DNA is still found in the sweeping scores of John Williams and countless others. (Star Wars’s original “temp track” of music, used during editing before its score was written, included music by Steiner.)

Max Steiner, circa 1936. Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University Library, Provo, Utah.

By the mid-1930s, Max’s trademarks were widely imitated if rarely equaled: separate, distinctive musical themes for characters, which he developed throughout a score to illuminate those characters’ thoughts and emotions; ingenious use of orchestral color to create atmosphere; and a gift for soaring lyricism that lifted dramas like Gone with the Wind and Now, Voyager into the realm of myth.

Best known for his work at Warner Bros. from 1936 to 1965, Steiner’s 300-plus credits include Casablanca, The Searchers, Mildred Pierce, The Big Sleep, and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. He was nominated for 24 Academy Awards and won three.

While retracing Max’s steps to write his biography, I realized why Steiner—a diminutive, wisecracking, but deeply romantic figure—related so strongly to the characters in his best-known films. Scarlett O’Hara’s fight to rebuild a family dynasty … Rick Blaine’s cynical wit that covers a broken heart … Kong’s vulnerability to beauty. All of these were part of Steiner’s story.

His life had the jolting plot twists typical of the Warner Bros. biopics he scored. During a pampered youth in late 19th century Vienna, Max was the presumed inheritor of a theatrical empire. His grandfather Maximilian launched the craze for Viennese operetta in the 1870s, after convincing waltz king Johann Strauss, Jr., composer of “The Blue Danube,” to write for the theater. Die Fledermaus, the world’s most performed operetta, was one result.

Max’s father Gabor was also a showman, fascinated by new technology; his productions ranged from symphony concerts to DeMille-like stage spectacles. Family friends included Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler. Even Austria’s emperor was a fan, decorating Gabor with the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Franz Joseph.

Papa Steiner’s most ambitious creation was the amusement park “Venice in Vienna.” Sixty years before Disneyland, the multi-acre venue offered a re-creation of the Italian city, complete with canals and gondolas. Patrons could ride rollercoasters, listen to gramophone records (then a novelty), and watch silent movies just months after cinema’s invention. Most popular was the Riesenrad, a Ferris wheel that remains one of Vienna’s most iconic attractions. Max reveled in “Venice”’s potpourri of symphonies, jugglers, waltz concerts and water slides. That pop culture mix proved ideal training for Steiner, who spent his life writing sophisticated, yet accessible, music for the masses.

He did not arrive in Hollywood until the age of 41. Until then, his life mirrored the rise and fall of Gabor’s Ferris wheel: early success thwarted by family bankruptcy; itinerant music-making in Paris, Cairo, Johannesburg, and beyond; and, in 1914, a panicked escape from London to New York, after the outbreak of World War I changed Max’s status in Britain from successful conductor to enemy alien.

Europe’s loss was America’s gain. During the 1920s, Steiner thrived as a Broadway conductor. He oversaw shows by Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein, and George and Ira Gershwin—most notably the Gershwins’ trailblazing Lady, Be Good! starring Fred Astaire. Conducting theater orchestras during a time before microphones, Steiner learned how to make sure music didn’t overwhelm a performer’s speech.

An invite from RKO to join its fledgling music staff brought him west in 1929. Within months he was made the studio’s musical director. Max’s early attempts to blend underscoring and onscreen dialogue were usually thwarted, by literal-minded producers who asked: where was the music coming from? But with scores like 1932’s Symphony of Six Million and 1933’s King Kong, Steiner proved that audiences accepted the unreality of an unseen orchestra accompanying the drama.

An Oscar win in 1936, for John Ford’s The Informer, cemented his reputation as leader in his field.

Whether overseeing the silky arrangements of Irving Berlin’s songs for Top Hat (1935), or writing snarling musical noir for James Cagney in White Heat (1949), Steiner set speed records for composing that were nearly superhuman. He thrived under pressure, writing scores in as little as a week if required.

Max Steiner conducts his score for King Kong (1933). Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University Library, Provo, Utah.

His score pages are filled with handwritten quotes of the movie dialogue being spoken at that moment (“Here’s looking at you, kid.” “It was beauty killed the beast!”). And somehow he found time to scribble notes in the margins sharing studio gossip, lamentations about his love life (he married four times), and sardonic, sometimes lewd commentary on screen action. His audience for these remarks was a private one: the orchestrators, who, like Max, slogged through days with little sleep to convert score pages into separate instrumental parts.

His jokes usually served a serious purpose: to keep his cohort alert, and to communicate dramatic intention. “Heaven music!” he wrote on the final pages of his score for Dark Victory, as Bette Davis bravely succumbs to a brain tumor. “Make this such a beautiful Heaven that no [studio] supervisor can ever get there!” On a 1952 religious drama: “Harps and Pianos are going ‘mad’ on account of the picture being just so-so.” And often, a comparison to the style of a beloved concert work: “A la Ravel’s Bolero—only better!” To keep his music from competing with dialogue, Steiner wrote above or below the pitch of an actor’s voice, after determining where that voice would be on a musical scale. In his score for the Bette Davis Oscar-winner Jezebel, he jots down that in her Southern belle accent, Davis “says ‘Am ah?’ … between [the notes] E and F.”

Steiner shaped not only how composers write film music, but how much they are paid. It was Max who launched a 27-year battle for film composers to receive royalties. (Until his efforts, studios paid a flat fee, and the royalty collection organization ASCAP ignored film music.) Today’s composers—some of whom make millions as their work plays on TV, home video, and streaming—have Steiner partly to thank.

Unfortunately, Max was both an innovator and a spendthrift. He earned millions, but spent even more on gambling, alimonies, alcohol, cigars, and generous handouts to friends in need.

A workaholic with manic tendencies, he was happiest when composing. Guilt led him to lavish his wives and his only son with everything except what they wanted most: his time. And although at age 71 he hit a financial jackpot—1959’s “Theme from A Summer Place” became the best-selling instrumental of the rock era—his failure as a parent would end in a tragedy from which he never fully recovered.

Fortunately, the music that was his addiction, and his escape from pain, still surrounds us. Every day, somewhere, a viewer’s heartbeat quickens as Steiner intensifies a classic moment of cinema: White Heat gangster Cody Jarrett’s defiant “Made it, Ma—top of the world!” The Searchers’s Ethan Edwards, played by John Wayne, cradling his long-lost niece in his arms. Scarlett O’Hara’s “As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again.” Or Rick and Ilsa’s farewell in a fog-shrouded airport in Casablanca.

It should be noted that Steiner did not write “As Time Goes By.” In fact, he hated the song, which was written by Herman Hupfeld in 1931, and had been largely forgotten. Entranced by Ingrid Bergman’s performance and her beauty, Max was eager to write an original love theme. But when ordered to weave Hupfeld’s tune into his score, Steiner created such heartbreaking variations that it’s hard to believe he didn’t love “As Time Goes By”— and compose it.

Typically, Max concluded his handwritten score for Casablanca with a joke to his orchestrator. “Dear Hugo: Thanks for everything! Yours, Herman Hupfeld.” It took him years to accept how effective that shotgun musical marriage had been. Without Steiner’s exquisite interpretations of Hupfeld’s melody—reimagined in the score as everything from a swooning waltz to a Puccini-esque lovers’ farewell—the song may not have attained its status as a pop standard.

Casablanca also demonstrates Steiner’s greatest strength as a composer: his gift for translating human emotion—grief, hope, romantic ecstasy—into music that still works its magic on 21st century viewers.

Just ask Steven Spielberg. In 2008, the filmmaker said of Casablanca’s score, “It just gets your heart. When you’re about ready to cry, Max Steiner comes in [and] those tears start to flow.”

Spielberg’s respect is also reflected in the nickname he uses for his favorite musical collaborator, John Williams. It’s also the name of Spielberg’s first son.

Max.

Listen to some of Max Steiner’s greatest scores:

Send A Letter To the Editors