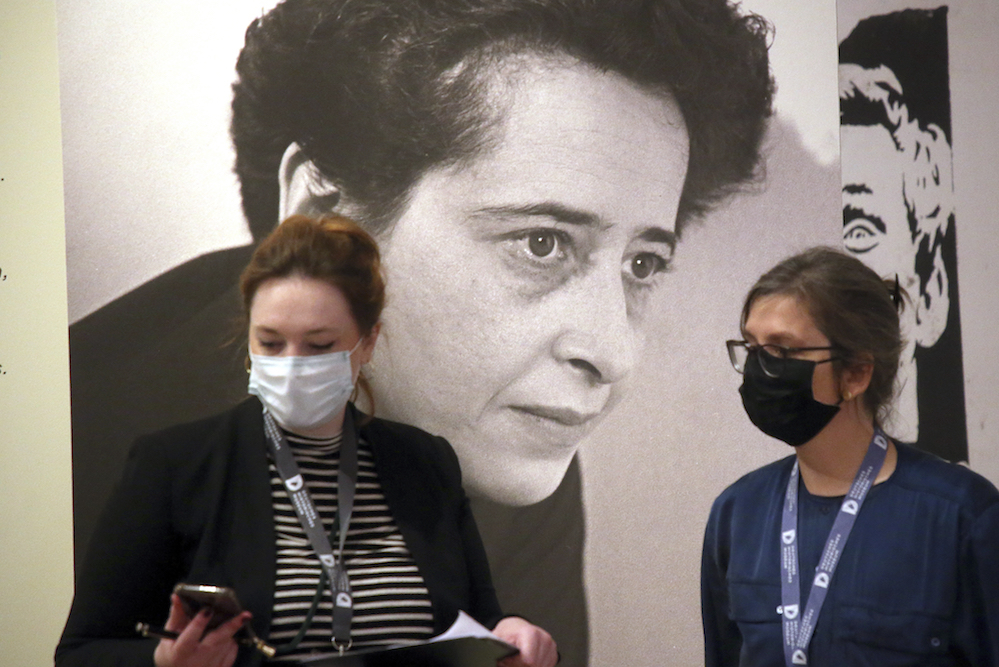

People wearing protective masks walk through the exhibition rooms on May 6, 2020, during the press tour of the exhibition “Hannah Arendt and the 20th century” in the German Historical Museum. Courtesy of Wolfgang Kumm/picture-alliance/dpa/Associated Press.

Hannah Arendt was one of the greatest political theorists of the 20th century. Arendt, who was Jewish, was born in Germany in 1906. She fled the Nazis in 1933 and ended up in the United States, where she devoted her new life to writing trenchant analyses of all things political—from totalitarianism to political revolution to war. A few years ago, I began writing a book about her thinking in response to the political partisanship, vitriol, and downright demagoguery of our age. I also wanted to introduce Arendt, who died in 1975, to new readers, and to defend what she called “authentic politics”—as she wrote, “different people getting along with each other in the full force of their power”—before those fed up with politics, or only interested in using it for their own personal gain. For Arendt, politics was the back-and-forth interplay between regular people in a democracy. Done right, politics not only combats hyper-partisanship and raw power plays, but helps us thrive, even in the face of great collective challenges.

When my book came out, the pandemic was just beginning. This was horrible timing, in many ways, as our collective worries about hyper-partisanship, misinformation, and the future of democracy took a nervous backseat to urgent concerns about testing kits, masks, hospital capacities, and staying safe and well. Arendt, as far as I know, never wrote about the politics of pandemic, and when my book went to press months ago, the world had never heard of COVID-19. And yet, trying to make sense of this illness and its broader impacts on life, I heard her voice in my head constantly. All the more so now, in the wake of the brutal deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery: I have been continuing to think with Arendt about our moment, our political moment, and I think there’s plenty we can learn from her insights about politics in a time of pandemic, police brutality, and protest.

The first and last thing Arendt teaches us is that politics was made for these crises. This may be obvious enough when it comes to police brutality and other forms of racist violence, but it is also true for the pandemic. While science, medicine, engineering, and manufacturing are essential to combatting coronavirus, it is politics, and politics above all, that creatively shapes how science is used, to whom medicine is applied, and how engineering and manufacturing are summoned to serve the public good. In acting collectively to care for others, we act politically. What is all this coordinating with innumerable perfect strangers to seek the good of our cities, communities, and neighborhoods, other than a form of political action?

We have a hard time seeing this because we assume politics to be the business of political parties, of Republicans and Democrats. Arendt’s writings try to disabuse us of this assumption.

Arendt was a widely respected intellectual in her own time. She taught at places like the University of Chicago and the New School. But she was more than an academic. She regularly commented in magazines and journals on the current events of her time—from Sputnik to the trial of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann to the Pentagon Papers to the civil disobedience of the Civil Rights movement—and indeed her whole intellectual career can be seen as an ongoing engagement with contemporary social, economic, and political crises. She brought to her commentary a wide range of ancient and modern thinkers, ranging from Socrates to Alexis de Tocqueville, Augustine to Immanuel Kant, John Adams to the 20th-century revolutionary philosopher Rosa Luxemburg. She consumed this vast history of American and European political thought in order to better think about the challenges and promises of politics. Writing during the Cold War, her political sympathies were neither highly individualistic nor communistic; rather, they were directed toward individuals working among others—sometimes in concert, sometimes antagonistically—to achieve new goals.

Her stature has only grown since her death. She is the subject of a documentary and a feature film, and of innumerable articles, conference gatherings, and books. The growing interest in Arendt is due, in good part, to the curious case for politics she made. She refused partisan labels, criticized partisanship, and opposed the concentration of state power—arguing that politics was distinct from all of this, and that it was a positive human good. When people gather together in relative freedom as equals to address matters of common concern, no matter what the issue, they reveal the capacity for people to truly make a difference. This is not populism, and it is definitely not partisanship. It is politics.

Arendt associated politics with birth, even miracles. She once wrote of politics, “Whenever something new occurs, it bursts into the context of predictable processes as something unexpected, unpredictable, and ultimately causally inexplicable—just like a miracle.” If politics is the art of different people getting along with all the power they have, the distinctive power of politics is different people getting along to change the course of things, stop the inevitable, and do something new. So, for example, people gather together and decide that there are other, better ways to organize our economy than around maximizing consumption and shareholder wealth. Would this seem miraculous to you? It would to me. But political movements have achieved, and can achieve, equivalent miracles, be it in the form of labor laws, civil rights achievements, the struggle for greater religious liberty, or public health movements.

Left to its own, the course and outcome of COVID-19 is inevitable. It will kill millions of people globally, and upwards of 200,000 in the U.S. But with effective collective action, we can reduce those numbers many times. The same is true of the systemic reform we desperately need to quash white supremacy—the systems won’t reform themselves, but with effective collective action we can do something new and better. These “buts” are not natural possibilities; they are political ones. It depends on you, me, and many others exercising our power to respond creatively to ruthless phenomena. As Arendt might put it, together—through authentic politics—we can orchestrate an “interruption” of the automatic, chain-reaction spreads of deadly viruses or racist violence. And that is what we are beginning to do across the land, and indeed in other parts of the globe, with some tangible, if early, success.

Some will say politics is to blame for all these problems in the first place, and that political leadership has failed us. The Trump administration stumbled into these crises and is still stumbling through them with a combination of callousness and incompetence. With coronavirus, had the administration acted sooner and with competence, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony Fauci memorably admitted, it could have saved lives that are now tragically lost. All the more, another administration might have seized on the public outcry over George Floyd’s murder to begin a process of major police reform. Political leadership has indeed failed us here. But it has also pleasantly surprised us, in certain cases. I think of innumerable community leaders who are leading the fight against coronavirus with tact and skill in communication and decision making. And I think of the organizers of innumerable marches and protests across the land.

I am reminded of something Arendt wrote about an entirely different kind of crisis, the short-lived Hungarian Revolution. During a few fateful weeks in the autumn of 1956, the people of Hungary revolted against their Moscow-backed Communist Party masters and formed local “councils,” with elected, non-partisan representatives, to serve as their new government. The revolution was over within weeks, and a new Soviet-style government reinstated—but Arendt saw in the powerful, if temporary, emergence of these Hungarian councils a vivid contrast between authentic politics and totalitarian domination. She noted, “while the naming of a candidate by a party depends on the party program or the party ideology, against which his suitability will be measured, the candidate in the council system must simply inspire enough confidence in his personal integrity, courage, and judgment, for someone to entrust him with representing his own person in all political matters.” Arendt found in this non-partisan form of “council” politics the eruption of yet another instance of authentic politics.

We see this echoed today in Dr. Fauci himself, whose great skill is political in nature. He knows how to communicate with honesty and tact; he displays as much good judgment as he does intelligence; having worked with presidents since Reagan, he knows how to navigate the Game of Thrones world of the White House without breaking public trust; and he shows courage. Fauci’s success in public leadership is not ideological—he does not toe the party line—and it is not strictly scientific either.

He commands authority for reasons that are entirely consistent with the qualities Arendt admired in Hungary’s council leaders: his integrity, courage, and good judgment.

In other words, in the response to COVID-19, we are witnessing firsthand the difference between partisan power and political power. The same, I would dare to say, is true of the protests against police brutality and systemic racism. Looking through the eyes of Arendt, it is plain that while President Trump has extraordinary partisan power, he has very little authentic political power—in large part because he lacks the virtues of integrity, courage, and good judgment we see in Fauci and any number of governors, mayors, health district leaders, school superintendents, and protest organizers. Thankfully, in this moment of profound crisis, persons of authentic political power are standing in to fill the void left by the president.

Is this political commentary? Absolutely. Is this partisan commentary? Absolutely not. And this difference between the partisan and the political is an essential point of Hannah Arendt, be it in a time of pandemic and protest or not. Totalitarianism and authoritarianism, Arendt argued, are perpetual threats, not once-in-a-millennium disruptions. Political parties, because they can so readily gravitate toward the seizure of power over respect for persons (though they need not), do not offer a reliable stopgap to authoritarianism. A robust democratic political culture, however, can.

Arendt was a creature of World War II. It was the defining event of her life, sending her as a refugee from her native home to the United States. After its utter wreckage ended, all sorts of thinkers offered all sorts of solutions to keep such a debacle from ever happening again. Some argued for world government, others for the restoration of a “balance of powers,” others for the expansion of free markets, and yet others for the construction of a deterrent military force. Arendt looked upon all these solutions with skepticism. The cause of World War II, she made plainly clear, was totalitarianism, a one-party system of total domination—and the key to preventing another global war would be to push back passionately on all attempts at the total domination of people, no matter what their form.

For Arendt, this meant making ample room for politics—”different people getting along with each other in the full force of their power.” She didn’t see authentic politics as a be-all-and-end-all solution, but it is resolutely set against any and all attempts to render human life mere fodder for ideological, statist, economic, or technological machines. Her vision of politics, we might say, was humane, and as such was oriented toward not just the preservation of life, but a concern for the quality of collective, communal life. She was inspired by the ways people could express themselves and act with others, escaping fatalistic resignation to the powers—or viruses—that be.

Today, some have already compared the impacts of COVID to World War II, and the world is pouring out into the streets to fight brutality. We need politics in the way Arendt described it. The near and longer-term future is not up to the powers that be; it is up to us. But don’t worry, politics was made for this.

Send A Letter To the Editors