Map of the United States showing the Kansas and Nebraska territories as they appeared following passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

When a Union soldier from upstate New York marched through Manhattan, Kansas, during the dismal Civil War summer of 1862, he was astounded: “All at once, as if by magic, a beautiful village rose around us, with large commodious churches, hotels, stores and [a] schoolhouse. We were surprised and delighted to see, where we supposed at most a few settlers’ cabins, a village combining the neatness, thrift, and comfort of New England, with the freshness and fine natural scenery of the West. Such is Manhattan, standing at the advance guard of civilization, bright prophecy of culture, refinement and progress.”

The idea for Manhattan, Kansas, was born in the turbulent years of the early 1850s, when America was alive with ideas, yet divided as never before—and lurching toward civil war. A call to take direct action to oppose slavery inspired this curious transplanting of architecture and people from New England to the far-flung frontier.

At the time, Southern states were grasping ever more tightly at their insistence that no changes could be made to the compromises that had permitted slavery to persist since the time of the Founding Fathers. An 1852 convention in South Carolina denounced “the fiendish fanaticism of an abolition spirit” and declared the state’s right to secede from the United States if the federal government sought to change existing slave laws.

Meanwhile, New England was percolating with progressive thought. This “American Renaissance” advanced not just the idea of a unique national literature, but larger convictions about racial and gender equality. In 1850, the first National Women’s Rights Convention met in Worcester, Massachusetts, featuring addresses by Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, and Frederick Douglass. And by 1852, the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a sensation, described as the “finest picture yet painted of the abominable horrors of slavery” in a Boston Post review.

It was in this divided atmosphere that the May 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act opened the Kansas and Nebraska territories to settlement and eventual statehood. The assumption was that Nebraska Territory would become a free state, while Kansas, under the sway of its pro-slavery neighbor Missouri, would become a slave state. The Act infuriated Northerners because it undid the Missouri Compromise of 1830 and allowed for the expansion of slavery.

New England Emigrant Aid Company trade sign made of sheet metal, painted black with gold lettering. The sign was most likely used at the Boston headquarters of the New England Emigrant Aid Company. Courtesy of Kansas Memory.

But the assumptions of the Act were disrupted by the social movements and civil rights discussions occurring in New England. An organization called the New England Emigrant Aid Company hatched a bold plan to transport New England settlers to the open hills and plains of Kansas Territory in 1854 and 1855, for the purpose of voting for Kansas to become an anti-slavery “free state.” In line with the ideals of the American Renaissance in New England, the principal founder of the Company, Eli Thayer, wrote that its goal was “to go and put an end to slavery.”

Thayer later wrote that the idea of an organization to support New England emigration to Kansas Territory struck him as divine inspiration, a way to respond with positive action to an intolerable political situation. As the U.S. Senate debated the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Thayer obtained the first corporate charter for his company from the Massachusetts governor.

Thayer was a Yankee reformer who had earlier founded a college for women in Worcester, Massachusetts. It’s not clear where Thayer, the son of a failed Massachusetts shopkeeper, found his zeal for progressive causes, but it fits squarely in line with his purported Unitarian faith and his lifelong appreciation for his education at the Worcester Manual Labor High School, which provided poor children, like him, a quality education in exchange for work on its farm.

By the time the Kansas-Nebraska Act was signed into law on May 30, 1854, the idea of emigration to Kansas Territory was becoming widespread. In a speech, New York Senator William Seward declared: “We will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Kansas, and God give the victory to the side that is stronger in numbers.” Thayer had been the first to propose the idea of organized emigration to Kansas; following his lead were the Union Emigration Society in Washington, D.C., and the American Settlement Company in New York City. (Pursuing a somewhat different approach was the Vegetarian Kansas Emigrant Company, founded in 1855.) Because the vote for the Kansas Territorial Legislature was coming in March 1855, Thayer and others wanted to place as many settlers as possible in Kansas by that time.

Throughout 1854, Thayer was extremely active in fundraising, speaking, and organizing parties of settlers. By December, Thayer’s company succeeded in sending off more than 600 New Englanders to Kansas Territory and had established one settlement, Lawrence. But the company needed even more colonists and wanted a second settlement in 1855. Fortunately, Thayer soon found the right man to help him fulfill those plans.

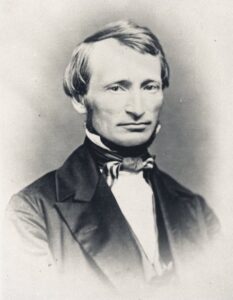

That month, Thayer spoke in Providence, Rhode Island, on the importance of Kansas emigration. “We have seldom listened to a more effective speech on any subject,” the Providence newspaper Freeman wrote of Thayer’s speech. Sitting rapt in the audience, his words captured the attention of a thin, stern Vermont native by the name of Isaac Goodnow. Goodnow was a 40-year-old teacher of Natural Science at an academy in nearby East Greenwich. After hearing Thayer’s speech and holding a private 90-minute conversation with him afterward, Goodnow became determined to support the movement by emigrating to Kansas Territory himself. He would go on to become the driving influence in gathering the group of settlers who would found Manhattan, Kansas—authoring speeches, letters, and newspaper columns supporting the movement. He was the acolyte that Thayer needed to ensure the new settlement’s success.

While Thayer saw the colonization of Kansas as an opportunity to achieve a worthy cause, he also recognized it as a potential moneymaking operation for its investors. On the other hand, Goodnow cared only for the cause. He viewed the settling of Kansas as one of the few ways a New Englander could live by his or her lofty ideals. In January 1855, Goodnow wrote a column in East Greenwich Weekly Pendulum pleading for action: “Kansas is, and may be for years to come the great battle ground of Freedom and Slavery! … While we talk, slave holders act. We have had enough of abstract, easy-chair speculations, it is now time for every man to show his principles by his works…. The only way to save the territory from the curse of human bondage, is for the men of … New England to rouse themselves, and emigrate by hundreds and thousands…. [W]e must be willing to endure hardship and privations. But who would not make sacrifices in one of the most philanthropic enterprizes of this age?”

Isaac Goodnow. Courtesy of Kansas Memory.

Shortly afterward, Goodnow was besieged with letters containing questions about Kansas Territory and requests to join the movement. “I am truly happy when I hear of men of influence who … go on to the ground with companies of men and contest the battles of freedom. Action is what is wanted,” one acquaintance wrote to him. Ultimately, through Goodnow and Thayer’s efforts, hundreds of New Englanders were motivated to make the trip in early 1855.

On an unseasonably warm March 6 afternoon, Goodnow and an advance group of 68 boarded a smoky coal-fired train in Boston to begin the first leg of their journey. It was a “tedious and tiresome” trip that would require more than two weeks of travel by rail, steamboat, and wagon. Crowding, lack of sleep, and dirty drinking water caused many illnesses along the way, some fatal.

The New Englanders had to pass directly through increasingly hostile Missouri to reach Kansas Territory, and the steamboats carrying the 1855 emigrants were sometimes stormed by drunken and armed mobs of pro-slavery Missourians. The pro-slavery newspaper Squatter Sovereign wrote of the New Englanders, “We hope the Quarantine Officers along the borders will forbid the unloading of that kind of Cargo.” The paper added, ominously, that “horrible disease, and one followed by many deaths … may be the consequence if this mass of corruption … is permitted to land and traverse our beautiful country.”

For some New Englanders, the discomfort and threats were too much. Although hundreds began the trip in early 1855, many turned back. Goodnow wrote in his diary that he “had to spend much time almost every day in encouraging the young men & keep[ing] them from going home.” Goodnow optimistically spun the situation, writing that the journey “has been so trying, owing to the dust, wind, and scarcity of provisions and fodder, that we get the wheat, while the chaff of emigration blows away, or does not reach us.”

When the New Englanders finally reached the spot Goodnow had selected for the settlement, many slept on the open prairie, unprepared for the cold early spring nights. Just days after their arrival, more than a dozen armed Missourians, described as “fierce, ignorant partisans,” stormed their camp on horseback, firing guns at their tents, intending to drive them out of Kansas. Ultimately, only about 50 New England settlers remained in Manhattan when it was officially established in April 1855.

But more continued arriving throughout 1855 and 1856, and the combined forces of nature and hostility did not succeed in driving all of the settlers out. The few hundred that remained throughout Kansas Territory from the estimated 2,000 who initially set off with the New England Emigrant Aid Company proved sufficient in number to create the anti-slavery stronghold of Manhattan and to decisively swing Kansas to become a free state.

The victory wasn’t immediate, and it wasn’t easy. When the vote was held for the first Territorial Legislature in March 1855, Manhattan was the only settlement in Kansas to vote for anti-slavery delegates, as pro-slavery men from neighboring Missouri flooded the territory’s other election sites. Things grew even worse in 1856, with bloody violence throughout Kansas Territory as pro-slavery and anti-slavery zealots battled. In August, a band of armed Georgians marched through Manhattan threatening violence, and troops from nearby Fort Riley were promptly dispatched to protect the town. Despite the threats and violence, Manhattan’s settlers remained committed to a peaceful process.

Through it all, Goodnow’s company kept their faith in the future, and in the end, Thayer’s audacious plan for New England Emigrant Aid Company worked.

Though they could be unrealistic and overly idealistic, the New England founders provided Manhattan with a powerful sense of purpose, as well as amenities that other frontier settlements rarely offered, such as a schoolhouse, a sawmill, and private college, which was converted into Kansas State University in 1863. Fortuitously, a group of 75 settlers arrived by steamboat from Cincinnati in June 1855 and focused on developing commerce in the new village. The combination served the town well. Goodnow later wrote, “The union of the two companies, of the East and of the West, produced a grand practical combination, the best kind of business compound to make the right kind of a town to live in and to educate our children.”

Ultimately, the New Englanders left a lasting imprint. Even 25 years after Manhattan’s founding, during Kansas’s Wild West era, visitors to the town opined that it presented a refined “Eastern” appearance. Beyond its physical aspect, to this day, the city continues to embody ideals and visions that the New Englanders carried to the plains in the 1850s—notably an emphasis on religion and progressive education.

Contemplating the long-term legacy of the New England Emigrant Aid Company settlers, Eli Thayer wrote in 1889: “Justice, though tardy in its work, will yet load with the highest honors the memory of the heroic Kansas pioneers who gave themselves and all they had to the sacred cause of human rights.”

Send A Letter To the Editors