Soldiers of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry at Fort Keogh, Montana, in 1890. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As a youngster, John Downing Weaver paid little attention to his mother when she told him stories of her and his father’s trip to Brownsville, Texas, in 1909. It wasn’t until the journalist was in his 50s that he got around to asking her about it. After all, it didn’t sound like a glamorous trip.

“Some Negro soldiers shot up the town,” she said, “and Teddy Roosevelt kicked them out of the Army.” Weaver figured his father, a stenographer for the House of Representatives, had been tapped to cover a trial for the soldiers and summoned to Brownsville, a town on the Mexico border.

“They didn’t have a trial,” Mrs. Weaver responded. “He just kicked them out.”

“But not even the President can go around kicking people out of the Army without a trial,” John said.

“Teddy Roosevelt did,” she insisted.

Just to prove his mother wrong, Weaver dug into the official records of the case housed at the Charles E. Young Research Library at UCLA. It turned out that his mother was right.

On November 6, 1906, Theodore Roosevelt signed Special Order No. 266. With a stroke of his pen, the president triggered the dishonorable discharge of 167 Black soldiers of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry stationed in Brownsville, Texas. Weaver’s father was sent down about three years later, to report on the proceedings of a court of inquiry composed of five retired generals.

Weaver, after meticulously researching the events, concluded that these generals were “less interested in righting the wrong than in making the wrong appear right.” Weaver, then a reporter for the Los Angeles Times “West” section, published his findings in a 1970 book, The Brownsville Raid: The Story of America’s Black Dreyfus Affair.

The research made its way to the desk of Los Angeles congressman Augustus Freeman Hawkins, who, working in tandem with Weaver, introduced a bill to exonerate the soldiers. On September 28, 1972, the United States Army formally cleared the soldiers of wrongdoing. But that wasn’t the full story.

The dishonorable discharge had cut especially deep because it came directly from the nation’s president. The Twenty-Fifth—one of America’s segregated units, also called “Buffalo Soldiers”—had fought bravely beside Roosevelt’s “Rough Riders” in Cuba, during the 1898 war with Spain. The Twenty-Fifth also served in the Philippines and took part in suppressing a local uprising there. After serving in what were essentially imperialist wars, the soldiers returned to their bases in the Southwest, where they frequently faced discrimination and violence.

In late July 1906, the first battalion of the Twenty-Fifth Infantry was transferred from Nebraska to Brownsville, to replace the all-white unit that had been there to provide security from potential incursions by Mexican forces. Confrontations between white citizens and the soldiers started immediately after they arrived. Local merchants refused to sell the soldiers food or items. One citizen severely beat one of the soldiers after blaming him for allegedly brushing up against a townswoman on the sidewalk. A customs officer accused another of being drunk, and pushed him into the river while he was trying to get back across the bridge from a rest day in Mexico. The soldier could not swim and nearly drowned before others reluctantly fished him from the water.

There were other incidents, but anxieties came to a head when the wife of a merchant alleged that one of the Black soldiers had tried to attack and rape her. There was no evidence to support this accusation, but no matter—it pushed tensions to the point of no return.

There’s no dispute about what happened in Brownsville around midnight on August 13, 1906, and into the morning of August 14. Gunshots suddenly rang out on the deserted, dusty streets along the dark corridor between Brownsville proper and Fort Brown, where the Twenty-Fifth Infantry resided. Unknown parties indiscriminately fired at a number of private residences. By most estimates, the shooting lasted about ten minutes. When it was over, a mounted police officer was maimed, and a young saloon barman was dead.

From the viewpoint of the town’s white citizenry and leaders and media, there was little doubt who had done the shooting. Over the next 12 hours, witnesses came forward to say that they had seen soldiers creeping around the dark streets with guns. This was mysterious, owing to the fact that the soldiers had been required, for their own safety, to adhere to a strict curfew that evening.

This curfew had been implemented because of several racist conflicts that had taken place over the previous three weeks in town. In the early morning of the 14th, the white officer in charge of the Twenty-Fifth inspected all of the battalion’s weapons—none appeared to have discharged any ammunition. But townspeople and the mayor found a few caches of bullet casings around the town. This gave the accusers all the evidence they needed to support their theory: that some members of the Twenty-Fifth shot innocent citizens, and the rest of them entered into a “conspiracy of silence.”

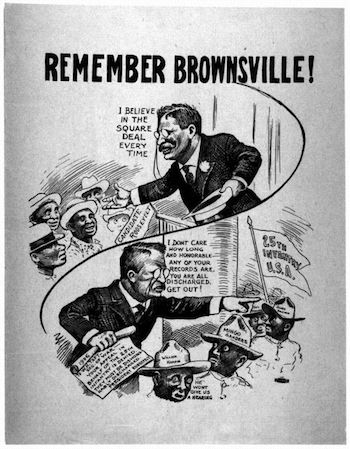

Political cartoon “Remember Brownsville.” Public domain.

It was for this “conspiracy of silence” that Roosevelt dishonorably discharged all 167 men and stripped them of their pensions and their ability to apply for any civil service job. For most of the soldiers, this was financially devastating—it meant a lifetime of menial labor, since a dishonorable discharge from the military far outweighed any positive recommendation for a position, especially for African Americans.

The townspeople of Brownsville assumed the soldiers had done the shooting in retaliation for ill treatment. And the War Department took the solders’ guilt for granted. In 1908, Republican Joseph Foraker of Ohio spurred a U.S. Senate committee to do its own investigation. He kept the issue alive in a bid to gain the party’s nomination but he also felt Roosevelt had exceeded his authority by dismissing the men without trial. In the end, the Senate committee wound up supporting Roosevelt. But there was significant fallout. Because of the unjust treatment of the soldiers, Black people voted against Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, in greater numbers than they had ever voted against any other Republican presidential candidate.

After a few years, Weaver notes in his book, the entire affair had been “swept under history’s rug.” Until, that is, Weaver brought it to the attention of Congressman Hawkins, Democrat representing California’s 21st District, covering southern Los Angeles County.

Augustus Freeman Hawkins spent 27 years in the California Assembly before entering the House of Representatives in 1962. As the first Black member of Congress from the western United States, he focused his career on bringing minority voices into politics. Among many other achievements, he sponsored a section of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 that established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. He had been in Congress only three years when the 1965 Watts riots claimed the lives of dozens of his constituents, causing him to redouble his efforts to secure funds to fight poverty in his district and all across the nation.

In March 1971, after reading Weaver’s The Brownsville Raid and having a staff member double-check some of its findings, Hawkins introduced a bill to exonerate the soldiers. It never got out of the Military Affairs Committee because the Pentagon wouldn’t support it. Hawkins began a series of correspondences with the Department of the Army, asking for financial relief for any surviving servicemen and their heirs. Members of Hawkins’s staff traced the discharged soldiers, placing ads in national newspapers and sending newsletters to various church groups, especially in the South.

Hawkins received an inquiry from the Judge Advocate’s office requesting more information about the Brownsville affair. Lt. Col. William Baker was working at the Pentagon in 1972 when he was asked to re-investigate the case. He pored through court transcripts, eyewitness accounts, contemporary news clippings, and military records. He also checked over testimony and ballistics tests, and even tried some re-creations. Baker later recounted that some of the 1970s military leadership did not wish to see him succeed in casting doubt on the decisions of the Army or President Roosevelt. Still, he turned over an exhaustive report that largely supported the innocence of the soldiers.

Hawkins heard nothing more about the investigation until September 28, 1972, when the Department of Defense announced that as a result of an “administrative review,” the records of the accused men would be expunged of the offense. However, the DOD made it clear that there would be no financial compensation available to these men or their families.

Hawkins was appalled. Members of Hawkins’s staff had found two of the 167 soldiers: Edward Warfield of California and Dorsie Willis of Minnesota. Warfield was one of a few who had been allowed to reenlist after the 1906 incident. He received an honorable discharge from the army after serving in WWI, and died in September 1973. Willis, who was 21 years old when he was discharged, had spent 60 years shining shoes in Minneapolis. He was in failing health, was crippled with arthritis, and had recently been let go from his job owing to his age. With Weaver’s assistance, Hawkins worked with Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota and others to introduce a bill that would provide compensation to Willis.

On January 10, 1974, in Minneapolis, Major General DeWitt Smith presented Willis a check for $25,000. It was a victory but not a total one, since Humphrey had asked for $40,000, plus past pension and veteran benefits. In addition, each of a dozen surviving widows of discharged Twenty-Fifth soldiers received $10,000.

Dorsie Willis died three years later. He was buried at the U.S. Military Cemetery at Fort Snelling, Minnesota with full military honors.

Send A Letter To the Editors