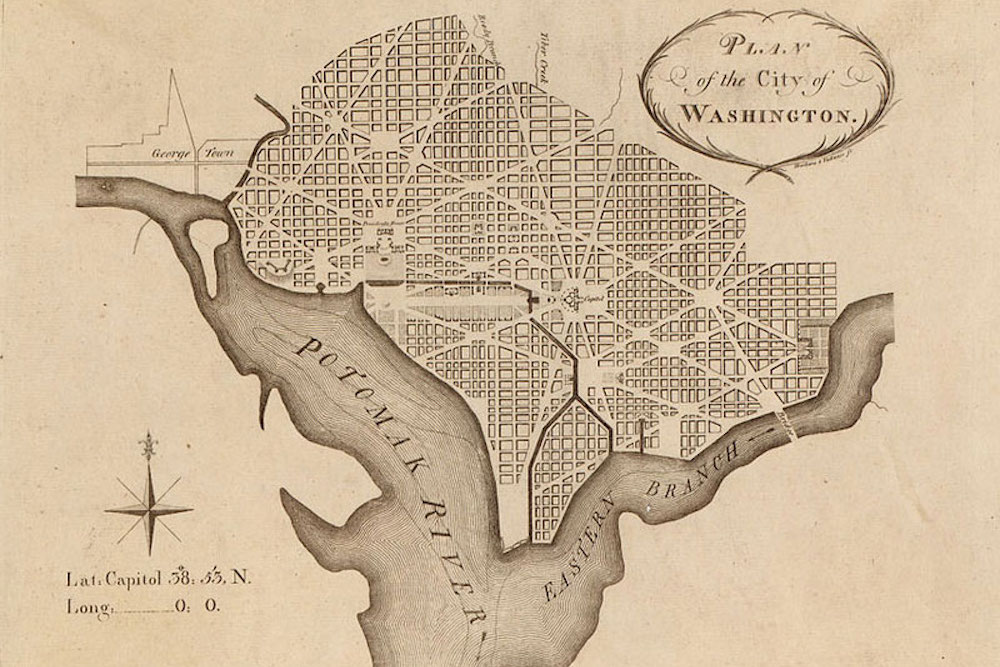

Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s Plan for Washington, D.C., as revised by Andrew Ellicott. Engraved by Thackara & Vallance sc. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Washington, D.C., was a capital not just of the United States, but of slavery, serving as a major depot in the domestic slave trade. In the District, enslaved men, women, and children from homes and families in the Chesapeake were held and then forcibly expelled to the cotton frontier of the Deep South, as well as to Louisiana’s sugar plantations.

Slave dealers bought enslaved individuals whom owners deemed surplus and warehoused them at pens in the District of Columbia until they had assembled a full shipment for removal southward. Half a mile west of the U.S. Capitol, and just south of the National Mall, sat William H. Williams’ notorious private slave jail, known as the Yellow House.

By the mid-1830s, the Yellow House was one more piece of the machinery that controlled slave society. Whip-wielding owners, overseers, slave patrollers, slave catchers with vicious dogs, local militias, and a generally vigilant white population, who routinely asked to see the passes of enslaved people whom they encountered on the roads, all conspired against a freedom seeker’s chances of a successful flight. Private and public jails lent further institutional support to slavery, even in the heart of the nation’s capital.

Some slave owners visiting or conducting business in Washington detained their bondpeople in the Yellow House for safekeeping, temporarily, for a 25-cent per day fee. But mostly it was a place for assembling enslaved people in the Chesapeake who faced imminent removal to the Lower South and permanent separation from friends, family, and kin. Abolitionist and poet John Greenleaf Whittier condemned “the dreadful amount of human agony and suffering” endemic to the jail.

The most graphic, terrifying descriptions of the Yellow House come to us from its most famous prisoner, the kidnapped Solomon Northup, who recounted his experiences there in Twelve Years a Slave. Northup, a free Black man from the North, was lured to Washington in 1841 by two white men’s false promises of lucrative employment. While in the capital, the men drugged their mark into unconsciousness, and Northup awoke enchained in the Yellow House’s basement dungeon. He vividly described the scene when his captor, slave trader James H. Birch, arrived, gave Northup a fictive history as a runaway slave from Georgia, and informed him that he would be sold. When Northup protested, Birch administered a severe thrashing with a paddle and, when that broke, a rope.

Northup, like most who passed through the Yellow House’s iron gate, was destined for sale in the Deep South. A few of William H. Williams’ captives attempted to evade that fate. In October 1840, Williams’ younger brother and partner in the slave trade, Thomas, purchased an enslaved man named John at Sinclair’s Tavern in Loudoun County, Virginia, for $600. Twenty years old, less than five feet tall, but referred to by the National Intelligencer as “stout made,” John escaped from Williams’ clutches while still in Virginia, but he was eventually apprehended in Maryland and retrieved by someone under William H. Williams’ employ. Despite his efforts to resist, John, like thousands of other enslaved people who ended up in the Williamses’ possession, was conveyed to the New Orleans slave market for auction to the highest bidder.

For the Williams brothers, every man, woman, and child they bought and sold were commodities in which they speculated. Their entire business was based on assuming the risk that they could buy low in the Chesapeake and sell high in the slave markets of the Old South. Occasionally, they even tried to profit by betting on people fleeing their owners. In 1842, Thomas Williams purchased two escapees from Auguste Reggio of Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. According to Williams’ agreement, “It is … understood that … Enoch and John are sold as runaway slaves & are now absent.” Nevertheless, Williams was so confident that the police state of the Old South would soon apprehend them that he paid $650 apiece for two absconded men he might never see. In an undeniable gamble, the slave dealer wagered that they would both be recovered and fetch a far more handsome price in the New Orleans slave market than what he had paid for them.

Despite the odds against them, certain enslaved individuals who fell into the Williams brothers’ orbit determined to resist the system that oppressed them. In 1850, William H. Williams placed advertisements in the Baltimore Sun to alert the public to five enslaved people who had evaded his grasp. In May, Williams offered a $400 reward: $100 apiece for 26-year-old James; 25-year-old Sam, who was missing a front tooth; 20-year-old George; and the ailing Gusta, described as “ruptured,” likely indicating that he was suffering from a hernia.

In August, Williams again sought public assistance, this time in the recovery of “my MAN JOE,” a six-foot-tall 26-year-old who had been recently purchased from a doctor in Fauquier County, Virginia. Joe absconded near Fredericksburg and was heading, according to Williams’ prognostications, for Pennsylvania by way of Winchester, Virginia, where he had a grandmother and other relatives. Neither runaway ad mentioned whether the escapee had fled while in transit to Williams’ Washington slave pen or from the Yellow House itself.

One dramatic escape attempt from the Yellow House was documented in 1842 by Seth M. Gates, an antislavery New York Whig in the U.S. House of Representatives. Writing as an anonymous “Member of Congress” in the pages of the New York Evangelist, Gates described an unnamed “smart and active” woman deposited in Williams’ private prison who, the evening prior to her scheduled departure from Washington for sale in the Deep South, “darted past her keeper,” broke jail, “and ran for her life.”

She headed southwest down Maryland Avenue, straight toward the Long Bridge that spanned the Potomac and led to that portion of the District of Columbia ceded by Virginia. “It [was] not a great distance from the prison to the long bridge,” Gates observed, and on the opposite side of the river lay the Custis estate and its “extensive forests and woodlands” where she could hide.

Her flight took the keeper of Williams’ jail, Joshua Staples, by surprise. By the time he secured the other prisoners and set off in pursuit, she had a sizeable head start. Also working in her favor, “no bloodhounds were at hand” to track her, and the late hour meant that Staples had no horses available. A small band of men at his immediate disposal would have to overtake her on foot.

Although they “raised the hue and cry on her pathway” to summon the public’s aid, the woman breezed past the bewildered citizens of Washington who streamed out of their homes, struggling to comprehend the cause of all the commotion along the avenue. Realizing the scene unfolding before their eyes, residents greeted this act of protest in starkly different ways. Those who were antislavery prayed for her successful escape, while others supported the status quo by joining the “motley mass in pursuit.”

Fleet of foot and with everything to lose, the woman put still more distance between her and her would-be captors. In this contest of “speed and endurance, between the slave and the slave catchers,” Gates related, the runaway was winning. She reached the end of Maryland Avenue and made it onto the Long Bridge, just three-fourths of a mile from the Custis woods on the other side.

Yet just as Staples and his men set foot on the bridge, they caught sight of three white men at the opposite end, “slowly advancing from the Virginia side.” Staples called out to them to seize her. Dutifully, they arranged themselves three abreast, blocking the width of the narrow walkway. In Gates’s telling, the woman “looked wildly and anxiously around, to see if there was no other hope of escape,” but her prospects for success had suddenly evaporated. As her pursuers rapidly approached, their “noisy shout[s]” and threats filling the air, she vaulted over the side of the bridge and plunged into “the deep loamy water of the Potomac.” Gates assumed that she had committed suicide.

The unnamed woman who leaped from the bridge would not have been the first enslaved person imprisoned in the Yellow House to engage in a willful act of self-destruction. Whittier, the abolitionist, mentioned that among the “secret horrors of the prison house” were the occasional suicides of enslaved inmates devoid of all hope. One man in 1838 sliced his own throat rather than submit to sale. The presumed, tragic death of the woman who fled down Maryland Avenue, Gates concluded, offered “a fresh admonition to the slave dealer, of the cruelty and enormity of his crimes” as it testified to “the unconquerable love of liberty the heart of the slave may inherit.”

In antebellum Washington, D.C., African Americans were smothered by a Southern police state that treated them as property and demanded that they labor for the profit of others. Thousands upon thousands were swept up in the domestic slave trade, their lives stolen for forced labor in the Deep South. But a few, like the woman who fled the Yellow House, courageously transformed Washington’s public streets into a site of protest and affirmed their personhood in the face of oppression. Now, more than a century and a half later, echoes of that struggle can still be heard.

Send A Letter To the Editors