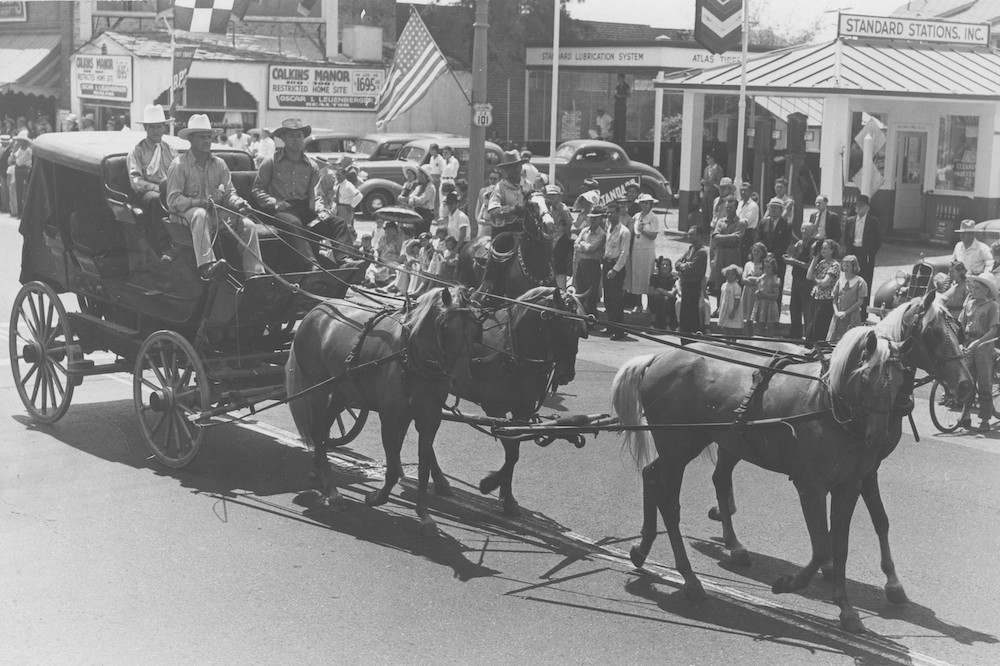

Pioneer Parade in El Monte. Courtesy of El Monte Historical Museum.

If we all agree that a lie is a lie, is that enough to replace it with the truth? If the people who started this lie are no longer here, why does it linger? Where does it get its strength? What do we need to defeat it?

This particular lie is at least 97 years old. Its exact origins are hard to trace, but its trajectory and path are rather easy to follow. The lie involves the Southern California city of El Monte, and you can find it in the title and subject of a small book published by the El Monte Lodge in 1923 called A History of El Monte: The End of the Santa Fe Trail.

That famous 19th-century trail, which turns 200 next year, begins in Franklin, Missouri, and ends in Santa Fe, New Mexico, nearly 850 miles east of El Monte. But by the 1930s, officials of that San Gabriel Valley city were holding public celebrations, putting up monuments to the Santa Fe Trail, and even staging a play called The End of the Santa Fe Trail at El Monte High School’s auditorium. This lie needed to be cared for, preserved, and displayed, so the city created the El Monte Historical Society in 1938. Throughout the 20th century, this lie has continued to endure, receiving support from mayors, councilmembers, and community leaders. It currently can be found in the city’s official logo and official museum.

Why this lie? It connects El Monte to Westward Expansion after the Mexican-American War of 1846-48, firmly lodging the city within the U.S. nation-state and cutting off anything or anyone that came before the first American families in El Monte in the 19th century.

“The pioneers of any new country are deserving of a big niche in our histories and we cannot love and respect their memory too much,” wrote the author of the 1923 book. How exactly one could love and respect someone’s memory too much is not clear. But in 1973, Lillian Wiggins, director of the El Monte Historical Museum from 1961 to the 1990s, affirmed the city’s exclusive devotion.

Speaking to the L.A. Times, Wiggins, a descendant of El Monte’s first American families, said that the museum’s collections were “strictly ‘wagon trail.’” By which she meant that the museum’s focus was devoted to the end of Santa Fe Trail, the so-called pioneers, and the wagons that brought them. This narrative stands in stark contrast against the demographic reality of El Monte, which has been home to significant Mexican American and Japanese American communities since the early 20th century, and in the last decades, has become a majority-minority city.

We’ve known that El Monte is not the “End of the Santa Fe Trail” since at least 1987. To celebrate the city’s 75th anniversary, city officials and a committee of El Monte residents sought to affirm their love and devotion to their so-called pioneers by gaining historical recognition from the state of California. In evaluating El Monte’s petition for a historical landmark, the state Historical Resource Commission provided an important corrective. In reporting the commission’s finding, the L.A. Times noted that El Monte marked “the end of some trail, but not the Santa Fe Trail.”

It did, however, note that El Monte was the first place to be settled by Americans rather than by Mexicans or Spaniards. And this was enough to feed the lie. The city council allocated $226,000 to make renovations to an existing park, to add a historical marker, and to proudly display a covered wagon.

The lie thus erased a lot of real history, including that of the first inhabitants of the land now called El Monte, the Tongva. And that erasure finally inspired a response on the occasion of the city of El Monte’s centennial, in 2012.

That year, the South El Monte Arts Posse (an arts collective I co-direct with the writer, journalist, and artist Carribean Fragoza), launched the public history project “East of East: Mapping Community Narratives in El Monte and South El Monte.” South El Monte is a separate, smaller municipality of 20,000 people, next door to El Monte, which has more than 100,000 residents. Since 2012, historians, scholars, and community members have conducted interviews with El Monte and South El Monte residents, scanned and preserved family photographs and city documents, dug into existing historical archives, and read through the existing scholarship.

Photo of Mexican-American youth as Adelitas found and digitized as part of SEMAP’s East of East project. South El Monte Community Center. Courtesy of South El Monte Arts Posse and South El Monte City.

This work is now chronicled in a book, East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte, which points out that El Monte is not the “End of the Santa Fe Trail.” But it says much more than that; in its devotion to the truth and to the area’s multi-ethnic present and past, it also shows how this focus on the “wagon trail” has erased and ignored the area’s most important events, people, and spaces.

Rather than the “End of the Santa Fe Trail,” El Monte and South El Monte have been the sites of conflict and contests, often driven by racial hierarchies, for the past 300 years. The area’s real stories are not about wagon-riding white pioneers but about rebellious leaders such as Toypurina, the Gabrielino medicine women who led a rebellion against Spanish colonial rule in 1785; the transnational Mexican anarchist and intellectual Ricardo Flores Magón, who agitated against the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz in the 1900s and briefly resided in El Monte; and El Monte native Gloria Arellanes, who held a leadership position in the Brown Berets during the Chicano Movement.

Over the past century, El Monte has seen a number of movements for equality. The 1933 Berry Strike was one of the largest organized labor strikes to challenge the agriculture industry of Southern California during the Depression. A decade later, in 1945, Mexican parents worked with Reverend Dwight Ramage and Father John Coffield, who served Catholic parishioners of El Monte’s barrios, to end school segregation. In the late 20th century, workers fought for their rights in South El Monte and El Monte’s factories. During the 1970s, the predominately Latino/a workers of the Sbicca factory organized a union and developed strategies to evade and contest Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) raids and deportations. Two decades later, Thai laborers found themselves in a more precarious position. They arrived to an El Monte sweatshop with the promise of labor, but found themselves unable to leave the property. They had to fight for their freedom.

El Monte also became an important space for Angelenos from East Los Angeles and other parts of Southern California. In response to “white only” beaches and swimming pools, Mexican Americans turned the marshland along the Rio Hondo into a recreational area known throughout Southern California as Marrano Beach beginning in the 1930s. Los Angeles writer and native Luis Rodriguez memorialized this “beach” in his memoir Always Running: La Vida Loca: Gang Days in LA: “In the summer time, Marrano Beach got jam-packed with people and song Vatos locos pulled their pant legs up and waded in the water. Children howled with laughter as they jumped in to play, surrounded by bamboo trees and swap growth.” And in the 1950s, Black, Chicano/a, and white teenagers throughout Southern California joined Art Laboe at El Monte’s Legion Stadium to create the first multi-racial dance hall in Los Angeles County.

The truth brings its own complications. Greater El Monte was also home to the El Monte Boys, who have long been depicted by the El Monte Historical Museum as men who heroically took the law into their own hands during the mid-to-late 19th century. The historical record, however, shows that they were vigilantes who engaged in mob violence throughout Southern California; most, if not all, supported the Confederate cause. They are part of a long-line of white supremacy in El Monte that continued in the early 20th century with the Ku Klux Klan—H.E. Wilhite of El Monte’s First Christian Church served as the KKK’s Kludd or spiritual leader—and in the 1960s and 1970s, when the city was home to the American Nazi Party’s local headquarters at 4375 Peck Road.

Michael Sedano, “El Monte, 1970.” Courtesy of Michael Sedano.

Despite El Monte’s multi-ethic past and present, the city remains tethered to the “End of the Santa Fe Trail” and its all-white pioneer narrative.

If we all agree that a lie is a lie, is that enough to replace it with the truth? If we remove the End of the Santa Fe trail from the city’s logo, what do we replace it with? If we were to empty the El Monte Historical Museum, what would we put in it?

This task can’t be entrusted to one person. We must rebuild our museum and the city’s official narrative the way folks built Marrano Beach and Legion Stadium, and the way folks fought against segregation and organized the Berry Strike of 1933. It is something that must be built collectively, working across generations and with all of Greater El Monte’s ethnic groups.

Send A Letter To the Editors