Brenda Moryck (left) pictured at the writing retreat of James Weldon Johnson in Great Barrington, Massachusetts (1928). Courtesy of James Weldon Johnson and Grace Nail Johnson papers.

In 1927, Brenda Ray Moryck, a 32-year-old Black American woman from Newark, New Jersey, published a manifesto in Ebony and Topaz, a prominent Harlem Renaissance anthology of prose and poetry.

In the work, titled I, Moryck, a graduate of the predominantly white women’s college Wellesley, writes that though she has suffered from racial discrimination, she finds “honey as well as hemlock in the cup of every Negro, sunlight as well as shadow.”

The piece conveys a profound sense of mission—even a calling—to help others: “But as a woman, what did I learn? … Work, play, and that highest opportunity, the opportunity to help and give, to mother and to heal,—are mine… I am a Negro—yes—but I am also a woman.”

The 1920s ushered in an extraordinary international representation of Black artistry and intellectualism in the United States. Called the “New Negro Movement” or the “Harlem Renaissance,” this artistic movement by African Americans from the United States and West Indies heralded an African American intellectual output and demand for representation that the world had supposedly never seen.

However, the term “New Negro” was misleading. African American cultural production had debuted with force in the 19th century when some of the most significant Black newspapers, poetry, and narratives that critiqued slavery were written.

Likewise, Moryck’s writings grew upon a long legacy of Black intellectualism and activism in her home city of Newark. A close examination of more than 100 years of archival records reveals clear examples of how Newark’s mid-19th-century Black abolitionism and Black women’s claims for justice were the foundation of the “New Negro” and the much later “Black Arts Movement.”

Wellesley College Portrait of Brenda Moryck. Courtesy of Wellesley College.

Newark’s significance looms due to its involvement in all of the major movements for abolition and activism of the period. It was a place where free and enslaved Black long-term residents and new migrants built some of the earliest African American churches, engaged in significant dialogues about emancipation, and led activist organizing, including forming societies and writing petitions about abolition and suffrage in the years before the Civil War. There, the Black activist community used its wealth, energy, and power to expand the dialogue about abolition and suffrage within the community and also assist with basic livelihood issues.

From the historical record, largely written by men, it’s possible to find brief glimpses of what life was like for Newark’s Black women.

For example, in 1804, an indirect note about the value of education appears when the Newark Female Charitable Society committee decided that “Mrs. Thibou was directed to pay Mrs Browns account of schooling Sarah a black womans children.”

Or in 1805, a newspaper article tells the story of a murdered Black woman named Polly, whose murderer, her husband, was hung in Newark’s Military Park. When Polly refused to reunite with her husband after he had her beaten with a stick, he tried to poison her two times and succeeded on the third.

By tracing the archive in this way, the early ways women worked to help each other becomes apparent. A church deposition documents the story of one African American woman offering to purchase the freedom of another. The woman, Jenny, offered to pay 50 pounds for Flora within a year. She received a handwritten note from Flora’s white owner, but Jenny could not read, and her employer informed her that the note for Flora was not a bill of sale. This deposition gives us insight into how Black women purchased freedom for themselves and others, even as some faced challenges like illiteracy and limited income.

The challenges that Polly and Flora would face, and the work that women like Jenny would do to help them, would essentially model much of the work that Black women progressive reformers, writers, and activists would do to liberate themselves artistically, socially, and economically after the Civil War.

Part of the reason it is hard to find Black women in the historical record is because early African American formal institutions in the city were male-centered. In 1818, Newark’s “African Society” allowed women and the enslaved to be members. However, they clearly stated that “None but male members may vote nor any under the age of 16 years.’”

But women’s work and importance within abolitionist organizations in the city ultimately forced public comment. By May of 1834, the “Constitution of the Colored Anti-Slavery Society of Newark” explicitly decreed that “any person” could qualify for membership. The “First August March” in Newark, celebrating emancipation in the West Indies in 1838 and 1839, indicated that the entire community took part, though all the scheduled speakers were male. By the time the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, renowned African American poet and Newark clergyman Elymas Payson felt it necessary to detail women’s influence and bravery when he wrote:

But whence that voice, so soft, so clear,

So musical within my ear?

It says “We’ll every power defy

Beneath which helpless women sigh,

And seek to mitigate their grief,

And toil and pray for their relief.

We will for fugitives provide,

We will the trembling outcast hide:

This will we do while we have breath,

Fearless of prisons, chains, or death.”

This voice is from the female band

Who are united heart and hand

With all the truly good and brave,

To aid the poor absconding slave.

Through the 19th century, Black women in Newark continued to take on more formal and public roles in civic life. Archival documents reflect how they worked expressly to reach the most vulnerable women and children and cultivate the minds of the privileged around political and artistic issues.

In June 1833, for instance, Christopher Rush, who helped found the first Black church in Newark, contributed to the formation of the Phoenix Society in Manhattan. The goals of this organization included Dorcas Societies—groups formed by women to collect books for circulating libraries and clothing for the poor.

This long legacy of women’s activism in Newark led directly to Brenda Ray Moryck’s 1927 manifesto. By the time Rose Moryck, Brenda Ray’s mother, was born in 1860 to prominent Newark abolitionist parents, the roles available for women leaders in Newark were transformative. In 1872, a female student integrated Newark schools. Prominent women began taking on the roles of teachers, including Harriet Brown, the daughter of Newark’s Underground Railroad leader, and Grace Baxter Fenderson, daughter of Newark’s first African American principal James Baxter. Fenderson went on to found Newark’s chapter of the NAACP in 1915. Rose Moryck would follow in their footsteps to become one of Newark’s early African American teachers.

This combination of empowering Black women with reform power and encouraging the circulation of books and “mental feasts”—meetings for intellectual cultivation and improvement—set the stage for organizations like the Phillis Wheatley Society and Sunday lyceums, all discussion groups that were organized in the 1910s by Black women in Newark. Rose Moryck, one of Newark’s African American teachers, was a prominent speaker at these gatherings, which included lectures on Black history.

Surely, women like Rose Moryck reflected the beliefs and practices of even white and immigrant women during that progressive era of reforms between 1890 and 1920. Women reformers regarded their agitation and social reform as extensions of their natural roles as mothers. But that work became more strikingly political among the women of Newark.

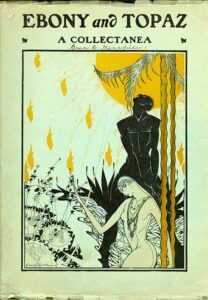

The journal Ebony and Topaz. Courtesy of Public Domain.

By 1922, Newark was hosting the national meeting of the N.A.A.C.P., while Grace Fenderson organized a parade to support the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill that was then in Congress. Prominent women’s groups marched, and groups of men and women carried signs reading “The Failure of the Anti-Lynching Bill Would Officially Condone Mob Murder.” A group of boys carried a banner that said “We are Fifteen Years Old. A Boy of Our Age Was Roasted Alive recently.”

This Newark community, a bridge between the abolitionist and reconstructionist past with a modern Black sensibility, prepared Brenda Ray Moryck to join the “New Negro” movement. After graduating from Wellesley, Moryck went on to write, organize, and teach in Newark, Brooklyn, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. She was an in-demand speaker, theater critic, and fundraiser, and, because of her family’s standing, a Black socialite. She worked with W.E.B. Dubois and other leaders of the Harlem Renaissance and the NAACP, published in Opportunity, and The Crisis, and also produced plays with the Harlem Experimental Theater and wrote theater criticism. Her peers viewed their artistic and activist work not as competing callings, but as complementary—using literature and art to facilitate social change.

Moryck’s first marriage was to a schoolteacher, an African American graduate of Harvard who died a year after their marriage. Her second marriage, 13 years later, was to a Black lawyer born in Haiti who she claimed graduated from the Sorbonne. She would move from Newark to Washington, D.C., and back to Manhattan.

While Moryck was very much a part of the Black elite, she was both enamored with and critical of the privileges and limitations of her caste. Her essay defending the Black elite of Washington D.C. against Langston Hughes’s denunciations of them in an August 1927 issue of Opportunity magazine as “pompous” and “pouter-pigeons” and the youth as “moving away from the race” is often cited in debates about the Black elite in the 1920s.

Her fiction explores the internal and external prisons of the elite. In I, Moyrck writes that her family’s economic and class privilege allowed her to not connect her Blackness to inferiority or caste until her adolescence. And in the short story Days, she writes of a middle-class African American couple being harassed and discriminated against by the working-class whites in her building. The wife, who seems to be modeled after Moryck, is shocked by their racism. Her character orders custom wallpaper, plays the piano, and even gets picked up by a famous Black entertainer in a car for dinner—fueling the class envy and bigotry of her white neighbors.

For the most part, Moryck was not ashamed of her middle-class upbringing and her commitment to aesthetics and beauty—rather it empowered her. As a teacher at both the Douglas High School in D.C. and Bordentown, she would lead the theater club and write letters about discrimination to visitors of the Black veterans in the soldier’s hospital. Being a member of the esteemed New York Committee of 100 (women) led her to highlight “disenfranchisement of the Negro in the South.”

Though she was comfortably middle-class and married by the 1940s, surely economic insecurity haunted her. In her 1941 biographical update for her biography at Wellesley College, she explains why she appeared to publish little under her own name. In the questionnaire, she wrote her “present position as “Writer,” adding: “because of prejudice, facts must remain knowledge of firm, by their request, as they claim many Caucasians would boycott magazines if they knew the author of some of their favorite stories was colored, since stories are not about Negroes! Since money rather than fame is my unworthy goal, I don’t mind loss of public acclaim.”

Moryck died in 1945, and she was buried in Newark in the same plot as her mother and father.

Today, Newark remains home to generations of Black women artists and organizers, who carry on the city’s long tradition of art, freedom, and justice.

Send A Letter To the Editors