Illustration by Be Boggs.

The stakes of the presidential election are huge and global. The results may determine the future of public health, the republic, even the planet.

The stakes of the presidential election are also peculiar and personal, especially for me. The results may determine which of two old friends—my fellow editors on our high school newspaper—ends up being the next Californian on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Mine is a strange circumstance. I spent my high school years, 1988 through 1991, at Polytechnic, a small (my graduating class had just 85 students) and academically rigorous private school in Pasadena. Late in my freshman year, I joined a group of students and a popular history teacher, Greg Feldmeth, in starting a school newspaper. We called it The Paw Print.

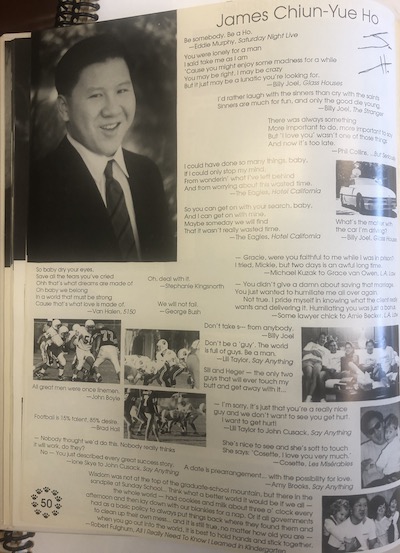

I became the paper’s first editor-in-chief, a job I shared with a classmate named Jim Ho, a doctor’s son from San Marino. Jim grew up to become, in 2017, a judge on the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Last month, President Trump added Jim’s name to the short list of judges he would appoint to the Supreme Court.

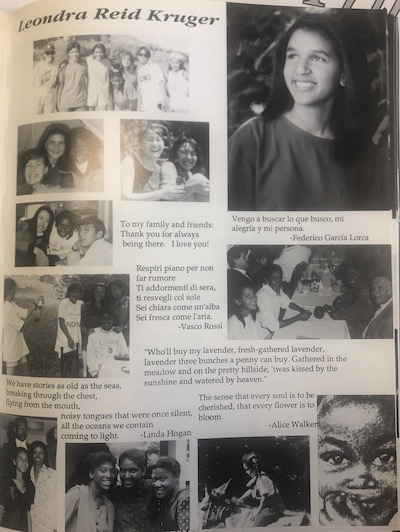

One of our smartest Paw Print reporters, and one of our successors as editor-in-chief, was Leondra Kruger, a doctor’s daughter from South Pasadena. Leondra grew up to become, in 2015, a justice on the California Supreme Court. Multiple press reports now identify Leondra as one of the top contenders to be Joe Biden’s first appointee to the Supreme Court.

Over the years, I’ve kept in touch with both Jim and Leondra, rooting them on as they rose through the legal ranks (while never missing a chance to tease them for wasting their journalistic chops on careers as legal functionaries). Since they became judges, I’ve read their opinions and marveled at what has changed, and what hasn’t, since I edited their raw copy.

But now that they’re real contenders for the highest court in the land, I’ve developed mixed feelings at the prospect of the ascent of either, especially in this frightening moment in American history.

When I turn on the news and see the toxic stew of American politics and the ugliness of a court confirmation hearing, I’m filled with fear for any friend of mine who might be thrust into such awfulness. And while I’m proud to know two people as great as Jim and Leondra, I also recognize that having two of the top two dozen high court prospects come from the same elite San Gabriel Valley school is not exactly an advertisement for American equality.

But my biggest fears are selfish. I’ve read of how the bitter political battles over the Supreme Court nominations of Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh ruined old friendships and divided the alumni community at the private school they both attended, Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown Prep. Their classmates were deluged with media inquiries, and I’m writing this column defensively, as a public statement to which I can point as I turn down the interview requests I’ve started to get about Jim and Leondra.

I’m also offering this as a prayer that our nation’s political and legal civil wars won’t eclipse my memories of high school days and divide my high school friends.

Those memories are mostly sweet. Poly mixed old-line Pasadena families with hyper-ambitious kids who had either fled (as I did) or avoided Pasadena’s struggling public schools. Immigrant families produced many of the best students, including Jim (born in Taiwan) and Leondra (whose mother is Jamaican). My AP chemistry teacher once dubbed me and the three other white kids in his class “the Caucasian Corner.”

Teachers were tough, and writing was emphasized; my fellow students included not only these two future judges but the screenwriters of Ocean’s 11 and School of Rock. Poly also had a softer side: It allowed you to try just about anything you could imagine. Jim and I were among those who imagined a school paper.

In that pursuit, we became fast friends. We ran the paper by rough consensus, with about a dozen editors deciding what to publish, often with Mr. Feldmeth’s counsel. Jim and I enjoyed stirring the pot, from arguing that the school tolerated too much underage drinking to investigating the ethics of water balloon attacks on freshmen. Jim made trouble by compiling a feature called “Paws and Claws”—a list of one-paragraph blasts of student praise and complaints.

Jim Ho’s Polytechnic yearbook page from 1991.

Jim was super-intense; he walked fast, laid out pages fast, and drove too fast, in a Ford Probe with so many extra options that The Paw Print’s car critic, whom I assigned to review student and teacher vehicles, called it the “Fordari Probarossa.” Jim loved arguing with our classmates and wrote with a passionate, sometimes over-the-top style. As his editor, I tried, and mostly failed, to tone him down as he campaigned to strip graduating seniors of the right to vote on the following year’s student government (since they wouldn’t live with the consequences of their choice).

I didn’t anticipate his judicial career, but I should have. He never missed an episode of NBC’s L.A. Law (he had a major crush on Susan Dey’s litigator). He had a strong sense of justice and helped crusade against what we saw as an unfair regime of student discipline. “Tardiness is treated as a more serious crime than cheating on exams,” the future Judge Ho wrote in his final Paw Print editorial. “Punishments must fit the crime, not the criminal.”

Leondra, a sophomore when we were seniors, was as cool and calm as Jim was hot and polarizing. One of the youngest people in her class, she could be funny and gossipy with friends, but she chose her words with great care, which made you listen more closely.

Leondra was deeply interested in the world outside Poly’s cloistered gates. She wrote for us about a Poly student who had left to go to public school and interviewed local teachers about California’s problems with education. As editor-in-chief, she published smart pieces about the school’s library, diversity, drugs, and even student sex. She also gracefully handled all the stories about the most traumatic event in our school’s life: the shooting death of a beloved student, Ochari D’Aiello, during summer break.

The Paw Print became smarter and more serious, with sharper editing and shorter stories, once Leondra took over. She ruled by consensus, in The Paw Print tradition, but had a strong backbone—she didn’t back down when people complained about coverage. When one student-contributor complained about his piece being cut, she replied: “When it comes to writers, sometimes people think their articles will only reflect on them, but in The Paw Print articles reflect on the newspaper as a whole.”

Leondra and I both went to Harvard, and we worked together again on the student newspaper, The Crimson. There she mostly resisted the urge to tell embarrassing stories about me to my girlfriend, another Crimson editor, now my wife. Leondra wasn’t the only future Supreme Court contender at the college paper; we became friends with Steve Engel, now a top Justice Department official who, like Jim, was recently added to President Trump’s Supreme Court list.

Leondra Kruger’s Polytechnic yearbook page from 1993.

After graduation, I became a newspaper reporter, which would rob me of most respect for the law (I’ve seen too much legislation written by the people and interests with money). But I kept tabs on the legal careers of Leondra and Jim with grudging envy. I couldn’t help but notice the contrast between the haphazard ways that careers advanced in the disintegrating media business, and the systematic ways my high school friends touched the different stations of the cross for would-be justices.

Leondra found her way to Yale Law (applying her Paw Print skills to serving as editor in chief of the Yale Law Journal), clerked for Justice John Paul Stevens, and worked in the U.S. solicitor general’s office, eventually arguing cases before the Supreme Court. She married a distinguished lawyer, and I’d thought California lost her to D.C. for good—until Gov. Jerry Brown unexpectedly called her home to take a seat on the state supreme court. Back in California, she has displayed her quiet intelligence and sense of duty—the L.A. Times reported that, just a few weeks after giving birth to her second child, she traveled to L.A. to hear cases.

Jim went to Stanford and worked briefly for state Sen. Quentin Kopp, a rare elected independent, before enrolling at the University of Chicago Law School, where his conservatism forcefully emerged. We kept in touch, and served as groomsmen in each other’s weddings. He worked in all three branches of the federal government—for Congress under Texas Sen. John Cornyn, in the Bush Justice Department, and as clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas. (I dutifully reported his high school driving to the FBI when interviewed for his background checks.)

Despite political differences, we stayed friends; he even got me into a Federalist Society event, where, despite aggressive reporting, I failed to spot anyone eating children or selling Supreme Court seats. Jim married a distinguished Texas lawyer—a dead-ringer for Dey—and followed her home to the Lone Star State, where he served as the state’s solicitor general, argued cases before the Supreme Court, and, to your columnist’s dismay, dropped his Southern California roots from official bios. The support of Sen. Ted Cruz, who had been Jim’s predecessor as Texas solicitor general, was crucial to Jim’s appointment to the federal bench three years ago.

If appointed to the Supreme Court, each of my high school newspaper buddies would be celebrated as a history-maker—Leondra as the first Black woman justice, Jim as the first Asian American justice. But, of course, they come from the same place, and I can’t help but see the familiar in their stories.

Profiles of Leondra sometimes include progressive activists and legal scholars complaining that she’s cautious, moderate, too grounded in the facts—just like the student journalist she was at The Paw Print. Jim, meanwhile, has gotten national attention for writing provocative, argumentative, and accessible judicial opinions, just like the pieces he authored as a student journalist. Critics say he writes too much like a columnist, offering opinions about policy and politics and morality, rather than just deciding cases. I confess that some of his rulings—like an opinion suggesting that giving police more leeway to use force would somehow stop mass shootings—make me wish I still had the power to edit him.

The overwhelmingly liberal majority of our old schoolmates would prefer to see Leondra on the court. I’ve watched her on the bench, and she is certainly the kind of judge I’d want with my fate in a court’s hands—smart, kind, and carefully even-handed.

On group texts, classmates sometimes grow angry at decisions made by Jim. (“Jimmy Crow Ho” was the theme of one bitter thread after he joined a decision making it harder to vote in Texas.) But our country, and the politicians who choose judges, seem to prefer jurists like Jim—attention-getting and forthrightly ideological figures who, like Antonin Scalia or Ruth Bader Ginsburg, can infuriate or inspire political bases.

We also prefer our judges young, which is why both my high school contemporaries are on short lists simultaneously. This is not because younger judges are better. It’s because these are lifetime appointments, and because those in power today want to lock their preferred judges onto the bench for as long as possible. Leondra and Jim are hot prospects since they’re in their mid-40s; in another 10 years, they might be considered too old for serious consideration.

This is a rotten state of affairs, both for the judges and the judged. I can’t imagine a more stressful time in life to ascend to a huge, high-profile job than in these sandwich years, when you’re both raising young children and taking care of older relatives. And for the country, giving such power to younger, less experienced judges is sub-optimal. Judges are supposed to consider long-term impacts and timeless principles, the sort of thinking that is better informed by age and experience. Ideally, America would have wise old judges who can check the excesses of young and energetic elected officials. Instead, America has things upside down. Our judges are younger and precious, while our most powerful politicians are tired, geriatric cases.

My biggest worry, though, is not about the ages of new justices, but about the court that Jim or Leondra might join. The sheer power of the U.S. Supreme Court is frightening, and growing. As our faltering republic finds it harder to resolve disputes and make progress, just five justices will have the power to make major decisions to cancel the democratic and life choices that we Americans make.

I have the deepest affection for these two judges I’ve known for more than half my life. There is no doubting their intelligence and their integrity. I would trust Leondra and Jim with that most precious of things, my children’s lives. And if I could reform the Supreme Court, I’d require its justices to operate more like The Paw Print editors of our day, with all nine required to reach a consensus before they publish any decision.

But, alas, our high court is not my high school newspaper. And I find it impossible to fully trust Leondra or Jim or any other living soul with the vast and unaccountable powers of a U.S. Supreme Court justice seat.

Send A Letter To the Editors