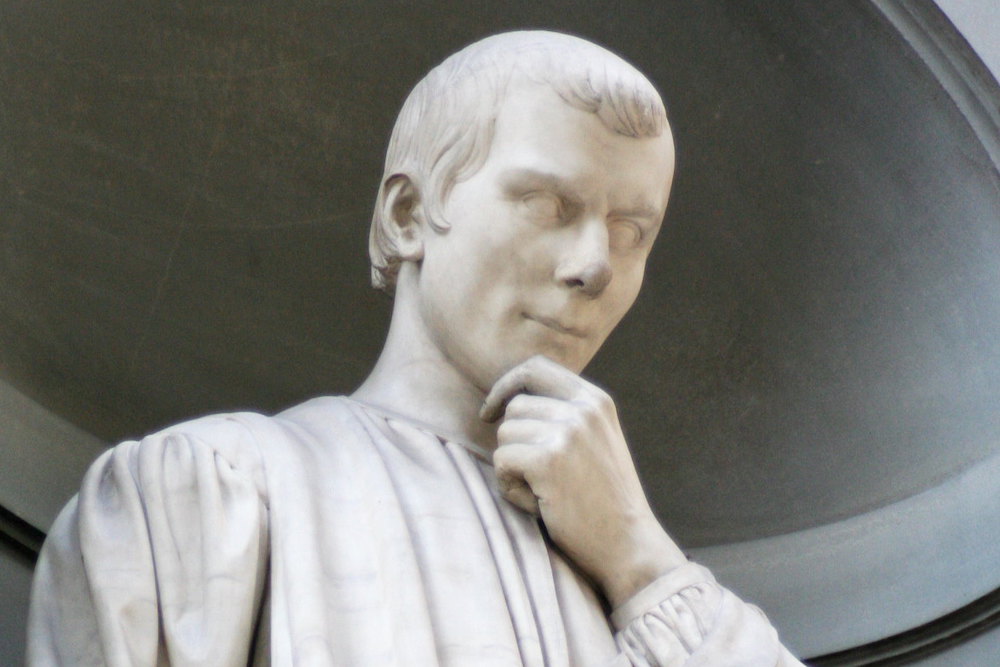

A statue of Niccolò Machiavelli in the arcade of Florence’s Uffizi museum. Courtesy of Elan Ruskin/flickr.

I have a mousepad on my office desk adorned with the Renaissance image of Niccolò Machiavelli and, beneath it in Italian, a very good question: Cosa farebbe Machiavelli? What would Machiavelli do?

Over the years, particularly at fulcrum moments in my life, I have engaged in silent discourse with it, staring into his ferret face and looking for guidance. I stared hard at it in November 2016, and I find myself asking for guidance now.

Machiavelli has been part of my life since junior high, when my history teacher assigned us book reports and I slyly chose the thinnest volume on the shelf. Little did I know that The Prince only seemed slim, and that it would metastasize in my teenage mind. Suddenly I saw the world through Machiavelli’s eyes and heard his aphorisms on political amorality seemingly everywhere. His words cut through the centuries and made him seem like he was right beside me in the here and now.

I read everything I could by him, not just the political stuff but also his wickedly funny play The Mandragola, written with the same uncannily clear eye for things as they are rather than as we wish they might be. But the original infection from reading The Prince has never quite worn off.

There is an unsolvable debate over whether Machiavelli wrote The Prince for the benefit of princes then and now, or for the rest of us to understand how power motivates princes in case we might need to wrest it away. Perhaps it’s both.

In his youth, Machiavelli was a junior diplomat for the short-lived Florentine Republic, where he observed up-close the rise and fall of Cesare Borgia—the quintessential prince and Pope’s son who for a moment wielded unbreakable power but whose untimely illness (most likely syphilis) led to his complete ruin. Not long after, it was Machiavelli’s turn to fall from Fortune’s Wheel; with the defeat of the Republic and the return of the Medici, he ended up not only jobless but jailed, tortured on the rack, and exiled from his beloved Florence. Disgraced and broke, living in the backwoods hamlet of Sant’Andrea, he spent his days in village taverns and his nights alone in his study, communing with the ancients through books.

It’s not hard to see that he would grow complex feelings and a love-hate relationship to governance, whether by tyrannies or by republics.

“Politics have no relation to morals,” is a quote attributed to Machiavelli. Our present Trumpian nightmare—with its hourly assaults on our democratic values and sense of common decency—spells these words out in skyscraper-sized gold letters. “He who seeks to deceive will always find someone who will allow himself to be deceived.” Machiavelli can be sickeningly insightful.

What would he have thought of our present moment, with our nation closer to civil war than at any time since Lincoln, and with our future on the precipice?

Trump would have fit Machiavelli’s model of the Prince in frightening ways. For one, the president’s ability to do the unexpected has thrown off his opponents and given him the tactical edge of always being on the attack, even when backed into a corner. For another, Trump’s ability to endlessly prevaricate for power’s sake has frustrated nearly everyone not wearing a MAGA hat. “A prince never lacks legitimate reasons to break his promise,” Machiavelli writes, “But it is necessary to know how to disguise this nature well and to be a great hypocrite and a liar.”

But in other ways, Trump falls far short of the model prince. His complete disinterest in learning how government works keeps him from obtaining full leverage in his power grabs, as does his inability to read or even listen to expert opinion. This would have irked Machiavelli to no end: He was one of the great readers in world history.

Still, reading our current predicament would have been challenging for Machiavelli. In the U.S., we seemingly find ourselves in a danse macabre, unwilling to give in to Trump’s worldview yet unable to fight him off.

Machiavelli says that “One must be a prince to understand the nature of the people, and one must be of the people to understand the nature of the prince.” Perhaps here Machiavelli hits on the secret of the president’s power. Trump may be a failed prince, but perhaps we are a failed people. Perhaps he reflects who we really are. Perhaps we deserve each other as we careen downward into the dust heap of history.

But as a playwright, Machiavelli also would have understood Trump less as a prince than as a figure from commedia dell’arte—namely the stock character Pantalone, known for his exceptional greed and his unrequited love for young beautiful women. Trump is even costumed for commedia, from the comb-over on his head to the wattle under his chin, from the orange Kabuki stage makeup to the poorly knotted red necktie. And this is where Machiavelli would laugh at the figure of Trump. It is not possible to be both Prince and Pantalone at the same time. We just won’t be able to take it all seriously over the course of a full play.

Of course, it’s not easy to laugh amidst the wreckage of our nation’s norms, but perhaps laughter is the antidote to the deadening poison that makes us feel powerless in the face of Trump’s execration.

Machiavelli might inspire us in other ways. He modeled resilience more than just about any bard not named Shakespeare. Through his writing, Machiavelli bounced back from exile and ruin and once more rose on Fortune’s Wheel. But it wasn’t The Prince that gave him back his fame; that slim volume would only go viral after his death. It was his plays that made him a player.

His deft onstage skewering of the prigs and charlatans of his time allowed his fellow Florentines to laugh at the old, established, entitled elite. The plays also posited a kind of revolution where the old decrepit system went topsy-turvy and where the ruling class got a well-deserved kick in the butt. The Mandragola was written during his exile, and its production allowed him to return home to Florence and to live alongside those who not so long before had tortured him.

“In the city of the blind, the one-eyed man is lord,” he wrote in The Mandragola. All it takes is one clear eye to see past defeat, bide one’s time, and take advantage of the opportunities that inevitably arise to send one’s enemy ass over elbows.

But if he were here with us now, cosa farebbe Machiavelli? What would he do?

“No circumstance is ever so desperate that one cannot nurture some spark of hope,” he wrote, also in The Mandragola. He would nurture hope in our hearts. He would have us commune with the ancients. And he would exhort us to plan for the fall of tyrants, and the return of our republic.

Send A Letter To the Editors