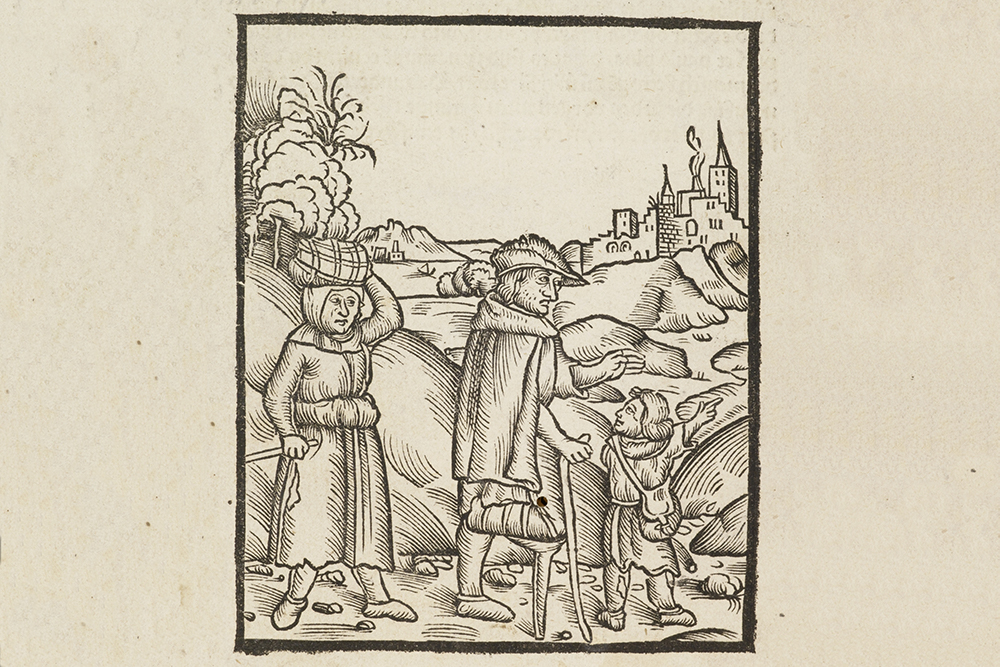

Woodcut from the popular Liber Vagatorum (“The Book of Vagabonds”). A Rotwelsch-German glossary of 219 items is preserved in the early 16th-century manuscript. Courtesy of Public Domain.

Have you ever been “in a pickle”?

Then you have encountered Rotwelsch, an ancient language of the road, spoken by vagrants and refugees, merchants and thieves since the European Middle Ages. This tongue was based on a combination of German, Yiddish, Hebrew, a smattering of Romani (the language of Sinti and Roma, pejoratively known as Gypsies), Czech, and Latin—and was incomprehensible to all but initiates.

I was inducted into this strange language during my childhood in Southern Germany. My earliest memories were of strange figures, dressed in long coats that had lost their original colors, who showed up at our door with bags slung across their backs. When it rained, they smelled, and my mother wouldn’t let them inside the house. “I know what you want. Wait. I’ll be right back,” she would say.

Lingering near the door, I would hear noises from the kitchen, my mother fixing open-faced sandwiches. While they ate, she remained standing on the threshold, guarding the house, trying to make conversation. I had trouble understanding them because they spoke a strange dialect, mixed with words I didn’t know. When they had finished, my mother would take the empty plate from their hands and close the door, relieved that the encounter was over.

“Who are they?”

“They don’t have a home. We’re giving them something to eat.”

That didn’t answer my real questions. I wanted to know why: Why didn’t they have a home; why were we giving them something to eat; and why did they have such a strange way of talking?

Later, I asked my father about these men and their language. “They are Travelers,” he said.

I didn’t understand. “Where are they going?”

“They are people of the road, escaping to nowhere.”

My uncle eventually figured out why these travelers kept showing up at our house. One day, he found a sign discreetly carved into the foundation stone, a cross with a circle around it, which meant that there was bread to be had here. The signs were called zinken, a word derived from the Latin signum. But the language was Rotwelsch, also known as kochemer loshn, an adaptation of the Hebrew khokhem, which means a wise person and loshn, tongue, or language.

It was a language of those in the know, the lingo of the wise guys. These signs and words pointed to an underground of traveling people; a world hidden away from view. Over centuries, outcasts had developed this secret world, with its coded lingo, to protect themselves from a world hostile to strangers (Rotwelsch means beggar’s cant). Their special language bound migrants together, because it distinguished those who belonged to the road from those who didn’t.

My father taught me some of their words. A barn was a stinker, and prison was shul (ironically derived from the German word Schule, or school). And then there was my favorite Rotwelsch expression, “being in a pickle.”

As an idiom, it didn’t make sense. A pickle was a delicious snack, so why should it have anything to do with being in trouble? The answer to that question: Because there was a Rotwelsch expression for “having a difficult time,” that sounded, in German, like Saure Gurken Zeit, which was taken to mean “being in a pickle” and assimilated into German (and later, into English). This is how you, too, have been speaking Rotwelsch without knowing it.

When I emigrated to the United States in the 1990s, I was surprised to find that Rotwelsch had preceded me. I got a first inkling when I came across hobo signs, which I recognized as being derived from Rotwelsch zinken, including the one that had drawn travelers to my childhood home. Central European vagrants had probably brought these Rotwelsch signs with them in the 19th century, a time of renewed immigration from German-speaking lands.

But the high tide of hobo zinken came during the Great Depression, when the signs were used in much the same way that Central European itinerants had used them: to navigate the difficult life on the road. The signs were adapted to suit the needs of their new users; a sickle, for example, would warn fellow hobos of dishonest farmers, who would hire you for a day and then cheat you of your wages. American hoboes sometimes walked the road, but they also sneaked rides on trains, which is why a sign emerged, that of a rudimentary train engine, to mark a good place to hop on a train.

Along with Rotwelsch zinken, Central European immigrants also brought their distinct way of speaking to the U.S. Once I started to look for traces of the language, I found them hidden here and there. The Jewish gangs of New York called a whorehouse nafke bias (a blend of nafke, Aramaic for difference; nekeyve, woman and; bayes means house in Hebrew), a thief gonef, just as Central European Rotwelsch speakers had done. They were also accustomed to going to school, meaning prison.

I have been thinking about Rotwelsch while stuck at home during the coronavirus lockdown, contemplating movement and mobility and how we talk about it. Only relatively few Rotwelsch words and signs made it to America, but the existence and persistent of the language raises questions that connect with today’s American political struggles. How much mobility are we willing to tolerate from those who seek to cross borders? To what extent will we accept people who don’t talk like us? How do we police vagrancy and homelessness? Rotwelsch has so many words for police, for prison, and for being arrested because of the increasing criminalization of mobile populations that continues to this day.

Throughout the 700 years of their history, Rotwelsch speakers have been persecuted by police, who didn’t appreciate their itinerant lifestyle and secret words. Countries and communities across Eurasia erected borders and invented passports to control the movements of people, which made the itinerant lifestyle even more difficult. At one time or another, Rotwelsch speakers have attracted the ire of every kind of oppressive ideologue in the modern world, including anti Semites, due to the Yiddish influence in their language.

If you’re looking for the ultimate outsiders, the ultimate scapegoats, Rotwelsch speakers, who numbered in the thousands or perhaps even tens of thousands at a time, would fit the bill. They were not ethnically defined (despite the anti Semitic attacks, which made them the first to land in Nazi concentration camps). All they had in common was the life of the road, the rejection of settled society—and their mysterious language.

When we emerge from the lockdown, a world that was already experiencing high levels of migration will see even more migrants, perhaps more than 100 million, many of them forced on the road by climate change and economic displacement. The future thus promises an ever-larger class of wanderers, many forced to live underground. Inevitably, some will develop new words and even languages as a protection against the police and as a source of identity.

What if Rotwelsch wasn’t a historical curiosity, but a harbinger of the future?

Send A Letter To the Editors