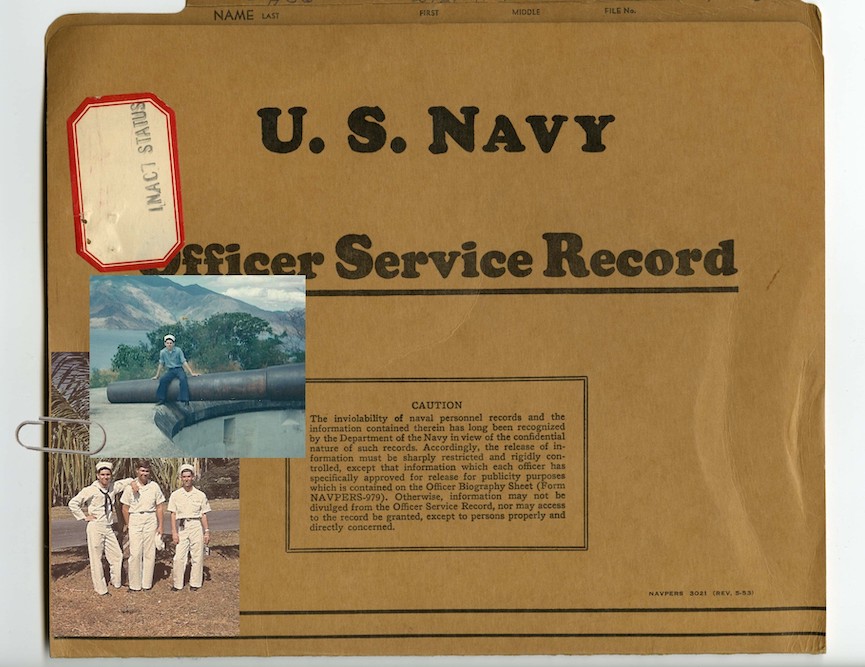

Vietnam War veteran Dave Lara’s “bad paper” discharge from the Navy followed him for decades. Photographs courtesy of Dave Lara; U.S. Navy Service Record courtesy of public domain.

I was 17 when I joined the Navy in 1965. My family was poor, and I was failing out of high school. Four years in the Navy felt like my only option.

I’d hoped to avoid ground combat by enlisting in the Navy, but within nine months of joining, I found myself in Vietnam.

During those long 13 months at war, the one good thing was the circle of friends I made, first as a hospital corpsman in an aid station in the jungle, and then onboard the hospital ship Repose.

The first gay man I met was at the aid station located in Dong Ha near the DMZ. His name was Matt, and we laughed when we found we both loved the movie The Group, based on the 1963 novel of the same name by Mary McCarthy. The story of the friendship of a group of Vassar College women who deal together with discrimination, jobs, and men, The Group also had a secret lesbian character who gave us an idea. Matt introduced me to a buddy of his, Joe, and together we bonded like the girls of The Group, and for the same reasons. We added more members who also loved the name—ultimately seven in all—and so we called ourselves “The Group.”

We were noticed, and maybe recognized as gay, but no one bothered us. I know some of our officers knew about us. It didn’t matter. We were in a war zone, and as long as we did our jobs, what the hell?

I had a difficult upbringing. I was born in a field on a farm in California’s Salinas Valley, and my father beat me from the time I was 7 years old. My mother tried to protect me, but one day my father nearly killed me by beating me with a pipe. He left, at my mother’s insistence, abandoning her to raise three children by herself. The last time I saw my father, he said, “I know what you are. I never loved you. I hate you.”

I hated the war, but suddenly because of the Navy, I had a place where I belonged. A family called The Group to share a life with.

Then in mid-December 1969, back stateside and stationed at the Quantico Marine Corp Base, the bottom fell out. I was summoned by the commanding officer of the Marines, who directed me to report to OSI, the Office of Special Investigation. I sat in a small room, where I waited for what seemed like hours. Finally, a man dressed in civilian clothes came in and introduced himself as a special agent of the OSI. He said allegations had been made against me.

I knew immediately what this was about. It was my secret, and it’d been found out.

“What allegations?” I asked anyway.

“You being a faggot,” he said.

I’d been turned in by a man called Anonymous. My military career ended even as I was coming to the very end of my enlistment. My year of service in a war zone counted for nothing. My passion for saving the lives of my fellow servicemen counted for less.

The OSI man said he wanted names and ranks of other homos I knew, and that I was going to have to submit to more detailed questioning by other agents.

“You will report back here to my office at 0900 tomorrow. Do you understand?”

A shipmate in Vietnam, David Monarch, had been arrested for being gay and removed from the ship. A very private man who’d kept to himself, he wasn’t part of The Group. But we all found out that he’d been court-martialed and sentenced to prison. Just months before OSI called me in, I’d gotten word that David had died at Leavenworth Federal Prison. I never learned how and why, but in 1960s America, we gay men deserved to die, according to popular thinking. So, who was going to investigate the fate of a queer Black man behind bars?

I was filled with terror at the prospect of dying like David.

I might as well die now, I thought. On my own terms.

Hours before I was supposed to return to the OSI office, I went to the small laboratory, where I worked as a medical technician. The bottles and beakers looked frightening in the thin 2 a.m. light.

Removing a Bunsen burner from the gas valve, I used the attached tubing to fill up a large plastic bag, which I then taped securely around my neck.

I shut my eyes. Was it the war? Was it the harassment for being gay? I didn’t know. All I knew was that I hated being gay and that I felt like I didn’t deserve to live.

As the gas replaced the oxygen in my system, my head started spinning, and I heard squeaky noises inside my skull. But then I realized I didn’t want to die. I didn’t want to give into them. I pulled the plug on the gas pipe, tore off the bag, and sat up.

After I reported my suicide attempt to the psychiatrist in my clinic, that stopped the legal proceedings in their tracks. Even the U.S. Navy wasn’t so cruel as to deny treatment to someone endangering his life.

I was first treated with strong psychotropic drugs and kept in a padded cell to protect the other patients from the “homosexual.” Later, I was released into the general population but kept on drugs with regular interviews and discussions with a military psychologist, all to treat my homosexuality rather than the PTSD I’d suffered because of the war, which remained undiagnosed. I spent nine weeks in the hospital.

Ultimately, it was decided that I must be discharged. A military medical board promised me a General Discharge under Honorable conditions—but it was qualified. On my Military Separation Paper DD214 were three codes: #265, unsuitability because of a character disorder; #256, admission of being a homosexual, acceptance of discharge in lieu of board action and punishment; and a re-enlistment code of RE4, unsuitable for military service.

This is known as a “bad paper discharge.” Other codes tell stories of drug use/sales, anger/aggression toward others, drunk driving, and any number of crimes or misdeeds. And there are other types of discharges, too, including Dishonorable and Bad Conduct Discharges.

These codes, and your DD214 form, follow you for the rest of your life. Employers can demand to see the form, for government jobs, especially; it indicates your job worthiness. The Veterans Administration will use it to see if you qualify for benefits, such as medical and retirement pay. Some of these General or even Dishonorable designations are the result of PTSD or traumatic brain injury; others are the result of the same mistakes a civilian young person may make, but in the civilian world there’s a chance they’ll forgive and forget these errors of youth. The DD214 is always the same and never changes. The codes give a picture of a person that is as one-dimensional as the ink on the paper.

A bad paper discharge can lead to higher rates of unemployment, homelessness, and suicide. For gay and lesbian people, the discharge has designations showing you as a criminal for many decades.

After getting out, I tried for a job at a city agency in Los Angeles. They refused to hire me after seeing the character flaw designation on my DD214. Later, I applied at Pacific Bell Telephone to become a janitor. They didn’t check my discharge; it wasn’t necessary for someone being hired to clean toilets.

On my discharge day, in February 1970, I went to Arlington National Cemetery to visit the grave of a man I loved. Matt had died a hero in my arms, the last week I was in Vietnam. I remembered how we had decided to create a tribe of our own. The other men, Matt said, had their support system all laid out for them. Surrounded by killing, we gay men needed to protect our minds, and strengthen one another.

As I stood at Matt’s headstone, rivulets of tears ran down my cheeks.

I was never religious. But I looked to the sky and hoped there was a God and that my Matt was with Him. I spoke the words I had said that moment when he died: “I wish we could have been lovers. I love you, man. I love you.”

Over the past 50 years, I have had many battles with the PTSD I suffer because of my war experiences, but I have also fought hard for the rights of Matt and other men and women like me.

It was only after I retired, though, that I began to think about correcting the injustice of my own discharge.

In 2016, I was volunteering at the Los Angeles County Department of Veterans Affairs, where I befriended the chief deputy director. She heard my story and helped me use her office’s resources to start my petition for a change to my discharge. It took four years, the help of a young gay psychologist at the VA Hospital and a high-powered legal team, and it changed my life. On June 3, 2019, my DD214 was administratively reissued to show a full and unqualified Honorable Discharge.

I now belong to veterans’ organizations where Afghanistan and Iraq veterans meet. They have struggles from their wars, and I suspect some have bad paper discharges. I show them that they can have a life—a long life—after service. They are my family now, my Group.

Send A Letter To the Editors