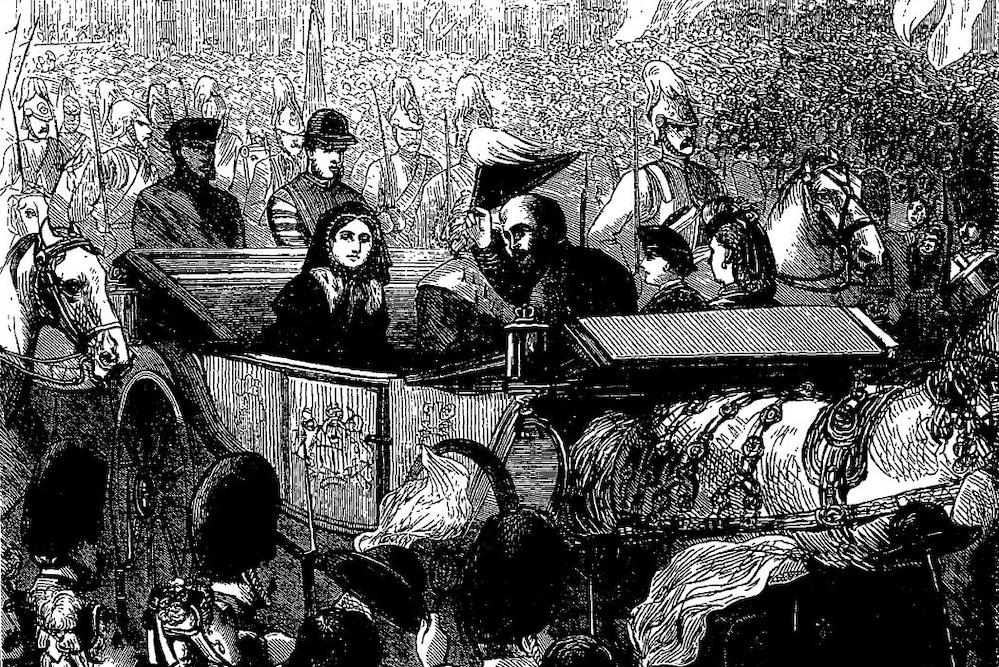

Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales head to the Service of Thanksgiving held to celebrate the Prince of Wales’s recovery from typhoid on February 27, 1872. Courtesy of Public Domain; sketch from The Penny Illustrated Paper.

In the early hours of Friday, October 9, President Donald Trump announced that he, like nearly 8 million other Americans in the past eight months, had tested positive for COVID-19. Days before, Trump had gathered in person with leading Republicans to announce the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. Against the advice of public health experts, few at the event wore masks, and there was little or no social distancing. Trump’s subsequent hospitalization at Walter Reed Medical Center offered an opportunity to change the public narrative on the COVID-19 pandemic; instead, the president fueled anti-science rhetoric, tweeting: “don’t be afraid of Covid. Don’t let it dominate your life.”

Presidential sickness during a public health crisis can have lasting effects on the direction of the nation’s public policy. In the spring of 1919, for instance, Woodrow Wilson contracted the so-called “Spanish Flu” but covered up his sickness because he worried it would upend the stability of post-World War I Europe. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s polio, on the other hand, galvanized the nation into public health action. Roosevelt wasn’t always forthcoming about his wheelchair use—during the early 20th century, Americans notoriously looked down upon disabled individuals—but in his second term as president, with polio rates remaining staggeringly high across the nation, he helped create the most successful public health campaign in American history, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, later known as the March of Dimes.

The most pertinent historical example to compare to Trump’s COVID-19 response comes from 19th-century Britain, when Queen Victoria’s son and heir, Prince Albert Edward, contracted typhoid fever, one of the deadliest infectious diseases of the period. After decades of ignoring or discounting one of the greatest health calamities of their age, a royal illness spurred British leaders, followed by the British public, to reframe the narrative around typhoid, characterizing it as a serious, preventable disease—and creating the first modern public health infrastructure, a system that still influences public health efforts today. Guided responsibly, Americans’ reactions to high profile COVID cases could have a similar impact.

Victorians always feared the next big outbreak of pandemic cholera, which arrived every few years and killed thousands during short bursts like the epidemic years of 1831-2, 1848-49, and 1853-54. But their everyday reality meant withstanding repeated domestic outbreaks of typhoid fever. Typhoid, which is caused by a strain of the Salmonella bacterium, is passed from person to person when tiny amounts of infected fecal matter contaminate food and water. In the 1800s, it was a fulminating, cluster disease, meaning that it erupted annually in cities, towns, and villages across Britain whose water supplies became contaminated. Typhoid killed up to 20,000 and sickened and debilitated up to 150,000 people each year.

The Prince of Wales caught the illness in the fall of 1871. Bertie, as he was affectionately known, spent two months in a feverish, delirious spell at the family’s retreat in Sandringham, looked after by two royal physicians, William Jenner and William Gull. All of Britain was absorbed with daily updates on the future king’s condition. When the prince began to recover in early 1872, there was massive jubilation, including a stunning public celebration in London in February marked by a royal procession from Buckingham Palace to St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The royal sickness that almost killed the Prince of Wales proved to be a turning point for Britain, which was at a political crossroads at the time. Queen Victoria had secluded herself in private mourning for a decade after the death of her husband, Prince Albert, in 1861, leaving the monarchy in shambles—and, as many republican critics believed—leaderless. In the way that only natural disasters like epidemics can do, though, the prince’s bout with typhoid brought the nation back together. On February 6th 1872, at the Opening of Parliament, a formal event that marks the first day of a new session, Queen Victoria returned to the public spotlight to give an energizing speech, where she thanked the entire nation for praying for her son “during the period of anxiety and trial” while sick with typhoid. The address restored the public’s faith in the monarchy. “Never before,” noted an editorial in the leading medical journal of the time, The Lancet, “has the bearing of all classes exhibited the strength of that common band of sorrowful sympathy which we are all bound together as a nation.”

That coming together was surprising because, up until Bertie’s prominent and public case of typhoid, most Victorians believed that the disease was the exclusive province of the urban-industrial poor—“the great unwashed”, to borrow the language of novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Indeed, that metaphor of filth, fevers, and fever dens in urban spaces was so ubiquitous that it had become a kind of literary trope in contemporary novels, like Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, and drawings, such as those by cartoonist John Leech in the satirical magazine Punch. Because of how the deadly epidemic disease had previously been framed—as the repose of the poor—any effective nationwide response to typhoid had been obstructed. The wealthy simply blamed the poor and went about their business.

The events of late 1871 and early 1872 changed the public narrative around typhoid fever. If the future king of England could get typhoid, so could anyone. Increasingly, well-placed Britons began to consider the epidemic “a national disgrace,” as one prominent doctor, Alfred Haviland, put it. Queen Victoria herself publicly declared that typhoid needed a national solution. Parliament responded swiftly, passing the first comprehensive sanitary legislation, the Public Health Act of 1872, followed by subsequent improvements in another act of 1875. Together, these acts compelled local authorities to provide municipal sanitation systems and hire permanent Medical Officers of Health, local public health officials to conduct disease surveillance and outbreak investigation. The acts also established a national disease surveillance system, centralized at the Medical Department of the Local Government Board, whose team of inspectors were charged with keeping track of and investigating infectious disease outbreaks throughout the country.

The United Kingdom had created the nucleus of the first modern public health system in the world and was the first to systematize the practices of state-sponsored epidemiology and allow it to thrive as the chief science of public health. In the period from 1872 to 1900, no other infectious disease was studied more closely than typhoid fever. When the central Medical Department was notified of a local outbreak, it would send an inspection epidemiologist, who interviewed local patients and doctors and performed case-tracing to ferret out the routes of disease communication. These early epidemiologists analyzed sickness and death rates in local communities where an outbreak was occurring, creating maps, diagrams, charts, and photographs in order to see, trace, and understand the spread of an epidemic disease. There were hundreds of local outbreaks to study, with each presenting another illuminating angle on how contaminated surface wells, leaking privy pipes, breakdowns in public water systems, and contaminated milk supplies contributed to widespread community outbreaks.

Everyday practices and methods of epidemiology still relied upon today coalesced and became routinized during this period. Through these investigations, Victorian health officials also realized that for widespread change in preventive public health to occur, epidemiological knowledge had to be communicated to various publics: local officials, business owners, lawmakers, and even everyday people. They relied on new rhetorical strategies, such as attending local town council meetings, writing in popular newspapers, and creating health promotional campaigns through handbills and other visual media—what today we call health communication.

By the first decades of the 20th century, typhoid rates declined sharply in the U.S. and western Europe, in large part because the typhoid problem had been treated as a systemic problem, with officials mandating and encouraging healthy, science-based improvements to the built and the natural environment, and successfully convincing citizens to change their personal habits. Apart from a few scattered outbreaks in the 1920s and 1930s, typhoid largely disappeared in the West, where today it is a long-forgotten memory, save for the infamous story of “Typhoid Mary,” the early 20th-century Irish immigrant cook in New York who infected dozens with the disease and was quarantined for decades against her will. However, typhoid remains a global health problem in the Global South, where it strikes 20 million and kills about 200,000 each year. A 2019 Lancet study called the disease an “invisible burden,” and recommended “global solutions: better data and better surveillance”—just the sort of innovations British epidemiologists introduced 150 years ago.

Smack in the middle of our own pandemic, we might rightly look back at typhoid as we consider how epidemiological knowledge is produced, defended, and debated, and how our leaders discuss the seriousness of the disease. It’s pertinent to note that typhoid policy bred skeptics, too. Epidemiologists in the 19th century frequently ran up against complaints that they were “meddlesome,” and “troublesome,” and had no “right” to tell local folks what to do about home and hearth—not unlike the backlash building against leading public health experts like Dr. Anthony Fauci and local officials like Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer.

Reckoning with the history of epidemics and epidemiology provides a salient reminder of how inextricably bound diseases are with politics and how personalities can clash with public health. Victorian health workers ultimately broke through the pushback by convincing everyday people—business owners, farmers, and politicians—that investing in removing structural causes of disease through the reduction of environmental pollution and the safeguarding of food and water supplies was both a public good and an economic good. Epidemiologists and political leaders today might mull what kind of rhetorical and communicative strategies will best help them discuss the cause and prevention of COVID-19 with everyday Americans and to reinvigorate those who are simply “over” the pandemic and the daily death counts.

Send A Letter To the Editors