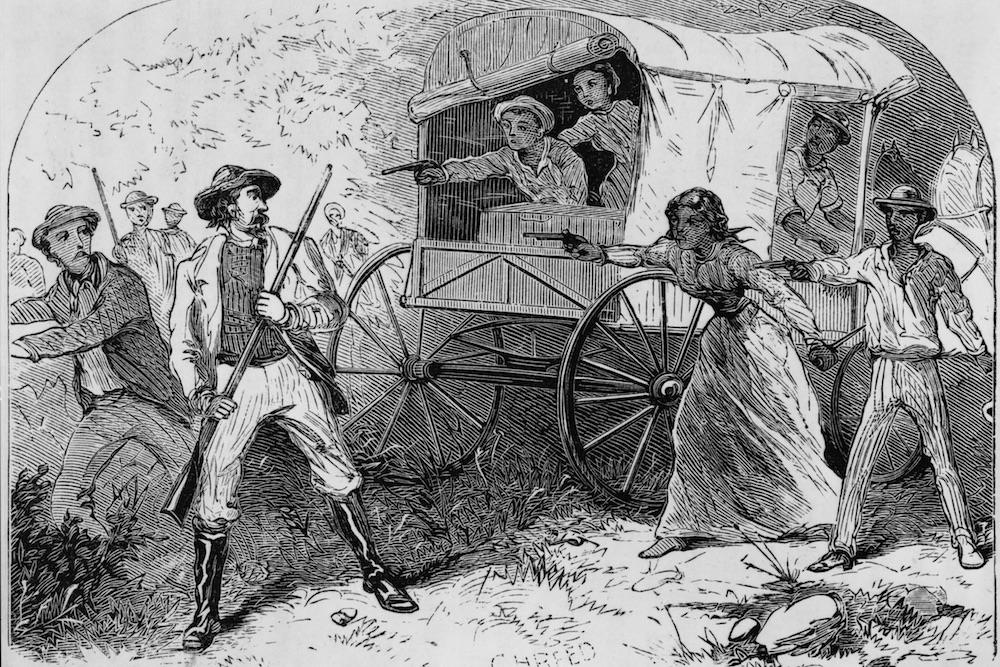

Many escapees fought back when slave-catchers pursued them. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Lower Mississippi Valley begins at Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River flows into the Mississippi, and extends south to the Head of Passes 100 miles below New Orleans, where the Mississippi empties into the Gulf of Mexico. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, white Americans flocked into the valley, the most ambitious settling in the delta region between Vicksburg and Memphis. There, climate and soil combined to create one of the best places in the world to grow cotton.

Some brought enslaved African Americans with them. Others purchased workers in the slave markets of New Orleans, Natchez, and Memphis, which had been stocked by traders who brought laborers from the Southeast, where owners supplemented their income by selling children away from their parents, and husbands and wives away from each other. Motivated by the possibility of getting rich quickly, planters drove their enslaved people without mercy, displaying little of the paternalism sometimes shown by well-established Southern planters to the east.

In all, more than 750,000 of these unwilling African American immigrants were brought to the Mississippi Valley between 1820 and 1860, their new lives far more difficult than their old ones had been. And so, they frequently fled. There were “heaps of runaways” living near Natchez, Mississippi in 1854, an elderly enslaved man told the future landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, then a correspondent working for the New York Times. They were seeking freedom from oppression—but also, like any other Americans, the opportunity to build better lives, in grand and small ways.

The history of these most persecuted of escapees is chilling. But it also gives us some idea of how people in impossible situations still managed to shape their own destinies.

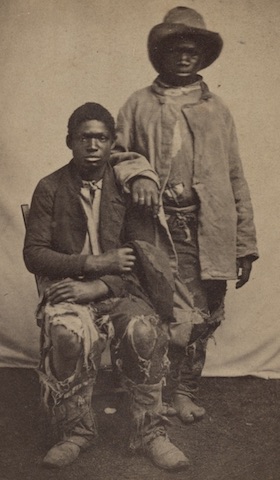

Enslaved men and women fled for many reasons, sometimes traveling hundreds of miles from home. Courtesy of McPherson & Oliver, photographer/Library of Congress.

Today we associate escapes from slavery in the United States with the Underground Railroad and heroic flights to Canada. But white Southerners used the word “runaway” to describe any enslaved person absent from his owner’s control without permission—and escapees sought freedom in many different ways.

Many left plantations for only a night or two to visit friends and lovers, or to attend clandestine parties and religious services. Others “lay out” in nearby swamps and forests for weeks or even months, or fled to cities and blended into Black communities made up of both free and enslaved people. Some who left for good tried to return to the places from which they had been taken. A few attempted to reach Mexico, which abolished slavery in the 1820s. Some headed north on steamboats.

Most runaways didn’t get far. In the memoir Twelve Years a Slave, Solomon Northrup tells the story of his friend Wiley, who had been enslaved in South Carolina, with a responsible job operating a ferry, before being sold to a trader who carried him to Louisiana. During the 1830s, Wiley wound up on Edwin Eppes’ small plantation on Bayou Boeuf in the northern part of the state, where Northrup lived as well.

One night, Wiley went out without permission to visit a friend. The local slave patrol caught him, unleashed their dogs on him, whipped him, and then took him back to Eppes—who whipped him again. Several weeks later, having had enough of his new home, Wiley tried to return to South Carolina. He escaped an early pursuit by fleeing into a nearby swamp, and made his way to the Red River, 20 miles away. He was captured and jailed in nearby Alexandria. Soon again he was working in Eppes’ cotton fields.

A few escapees managed to return home. In 1836, a man named Sam fled on foot from Mississippi to South Carolina, where he was from, only to be seen by local residents in Barnwell County, who armed themselves and gave chase. Hunted like an animal and armed only with a knife and club, Sam was hit by bird shot but refused to surrender until receiving a mortal wound.

Ginny Jerry was a determined runaway who fled often but always remained close to owner Bennett Barrow’s large plantation in Louisiana’s West Feliciana Parish. Barrow kept track of Jerry’s frequent escapes in his diary, sometimes getting angered when Jerry came back from prolonged escapes heavier than when he left, presumably thriving. An 1856 editorial in a Baton Rouge newspaper raged about the way runaways like Jerry fed themselves. “These runaway slaves kill your cattle … they do not remain all night in the dark, dreary swamp … they visit your servants in your own yard … there is scarcely a night of the week that your poultry yard is not inspected by some black rascal.”

In the fall of 1837, Jerry was gone for six months until Jack, likely another of Barrow’s enslaved workers, found him, beat him badly with a club, and brought him home. But Jerry persisted. Once in 1839 he claimed to be sick, and Barrow told him to “work it off,” but the servant instead chose “to woods it off.” Ginny Jerry’s last recorded escape occurred in 1845. It ended after three months when Barrow hired professional slave catchers to find him. Their dogs tracked Jerry and forced him into a tree; Barrow allowed the animals to pull Jerry down and savagely bite him.

The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole brought their enslaved people with them on the Trail of Tears to what is now Oklahoma. In one noteworthy account of escape, an enslaved named Ben, who had been left on the eastern side of the Mississippi, ran away from his owner to follow his wife, who had been sold to a Choctaw man who took her west. Ben was captured and jailed in St. Francis County, Arkansas, but broke out and continued his journey.

Enslaved people in the Lower Mississippi Valley were less closely supervised than those in the country; urban owners relied on their enslaved servants to shop, run other errands, and bring in money while “hired out” to work for other people. This was especially true in New Orleans, where the population in 1850 included 90,000 white people, 10,000 free Black people, and 17,000 enslaved people. In a typical 12-month period in 1853 and 1854, some 1,300 enslaved people were arrested as runaways—although most of them might be better described as walkaways, since they left one part of the city only to relocate in another.

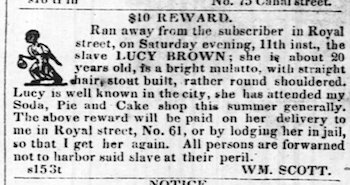

Advertisements for escapees in the New Orleans Daily Picayune suggest that many intended to pose as free people and use their previous experience to get paying jobs. Among them was a young woman named Lucy, who was well-known to customers in her owner’s “Soda, Pie, and Cake Shop.” George Anderson’s pre-escape career included work as a livery stable hand, a horse-drawn cab driver, and the operator of a milk wagon for Citizens Dairy. An enslaved man named Gus did carpentry work, Dennis built barrels, Philina was “a superior dressmaker and seamstress,” Susan dressed hair, and Ben Nash unloaded bales of cotton from steamboats.

A reward posted in the Daily Piayune for capturing an escapee. Courtesy of the Daily Picayune (New Orleans), September 17, 1841.

Some fled for the North on steamboats, often assisted by boat crews that included enslaved people and free Blacks. The Daily Picayune was convinced that “colored stewards, or cooks, or hands on boats use their cunning and the means peculiar to their positions to conceal slaves on board boats till they reach safe places for landing.” The ease of steamboat travel created an opportunity for individuals not suited for long escapes on land. Eleven-year-old Harry, who was 4 feet 5 inches tall, managed to avoid discovery until his boat got north of Vicksburg. He wound up in the Chicot County jail in southern Arkansas. Peggy, a “delicate and small” woman who worked as a milliner in New Orleans, fled with four dresses as well as what the Adams County jailer in Natchez, Mississippi, called “many other articles of clothing too numerous and too tedious to enumerate.”

The people best positioned for successful escapes were those who worked on steamboats. John Scott had already fled from one boat and been captured on another when John McMaster of New Orleans purchased him at a bargain price. McMaster, anxious for the $25-a-month that Scott earned as a cook, sent him out on at least three different steamboats, and the upwardly mobile man rose to second steward on the Louisiana before he jumped ship in Louisville, in the slave state of Kentucky. The record stops there, but he may have gotten someone in the Black community there to ferry him to freedom on the north side of the Ohio River.

Enslaved people often faced violence when they tried to flee. White southerners viewed apprehending runaways as a civic responsibility. Many were also attracted by the $10 they received by law for taking captives to jail, as well as rewards sometimes privately offered by owners. Non-owners were not supposed to damage other people’s property except in self-defense, but the law was seldom enforced, and many Blacks were killed while on the run. In the early 1850s, for example, near Marksville, Louisiana, the Picayune reported, “a young man shot a negro boy, supposed to be a runaway,” and a young man in Union Parish who killed a runaway was said by the Picayune to be “justified in the act”—without further explanation.

Fugitives sometimes fought to prevent being captured. One runaway killed the overseer who found him entering a slave cabin on a plantation near Woodville, Mississippi. A man was ferrying Bill and Roland to jail in a rowboat on Bayou Salle in 1842 when the two captives got loose, threw him overboard, and shot him in the water with his own gun. In New Orleans a runaway escaped after stabbing two men who tried to capture him; participants at a Congo Dance threw bricks at three police officers who attempted to arrest a fugitive among them; and someone murdered a slave catcher, targeted because of his profession.

From “fugitive slave” to “runaway,” the historical language used to describe these people who were fleeing from injustice and oppression does not adequately describe their experience. Risking life and limb for the chance at various degrees of liberty from bondage, today they are being recognized for who they really were: “freedom seekers.”

Send A Letter To the Editors