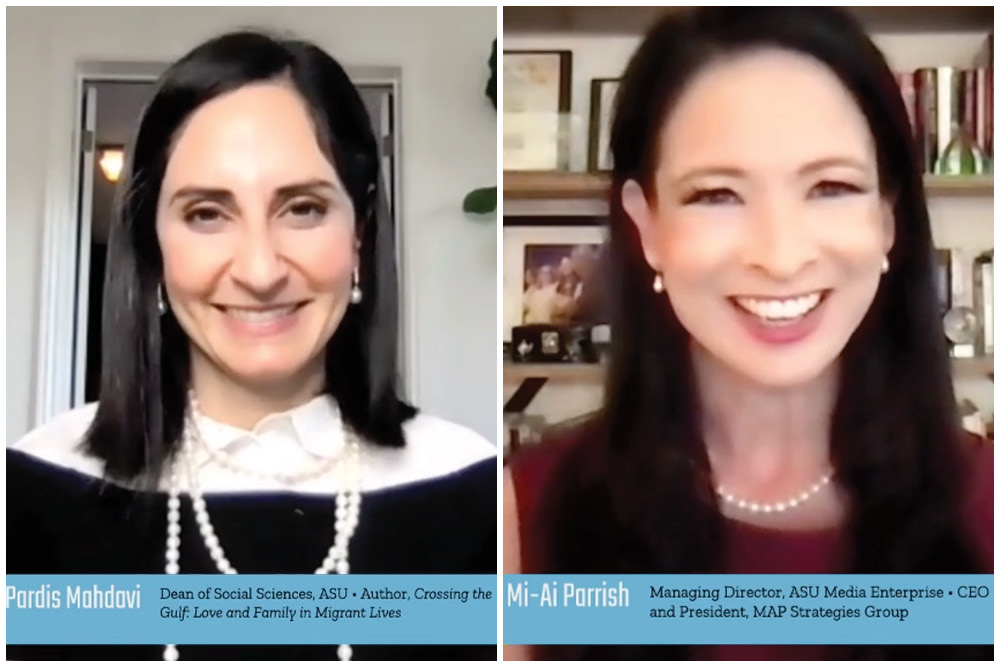

Pardis Mahdavi and Mi-Ai Parrish discuss "Can Women's Movements Save the World?"

Can transnational women’s movements save the world?

That was the title question posed, on International Women’s Day, to two Arizona State University experts on women’s leadership at a Zócalo/ASU Center on the Future of War event.

“In a nutshell, I would say yes,” said Pardis Mahdavi, the dean of social sciences in Arizona State University’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and an anthropologist whose scholarship covers gendered labor, migration, sexuality, human rights, transnational feminism, and public health. She said that transnational feminist movements—from #MeToo to #BringBackOurGirls in Nigeria—are having “a moment” now after many years of organizing.

“Feminist organizers have been working in the underground, they’ve been planting those seeds, they’re the tillers of the soil, if you will,” said Mahdavi. However, she cautioned, “we have to create an ecosystem where this change can take root.”

What differentiates feminist organizing from other types of movements, asked Mi-Ai Parrish, managing director of ASU Media Enterprise, and the moderator of the event, which was co-sponsored by the ASU Global Human Rights Hub.

“Feminist organizers,” Mahdavi replied. “they do their homework, they know what the lived experience is about, and they also know you need multiple disciplinary perspectives, multiple trainings. You’ve got to bring different people to the table to solve world’s most pressing problems.”

Transnational feminist movements aren’t limited to women-centric issues, like reproductive rights, she said. For example, Black Lives Matter was founded by three Black women in response to police violence against Black men. Or take feminist groups in Iran who have pushed back pushed back against morality police, Mahdavi added.

“What all these movement have in common is they’re all part of justice feminism,” said Mahdavi, defining justice feminism as “a uniting call that brings all these movements together” whether they’re about health justice, social justice or climate justice.

Mahdavi said that she finds hope in the greater intergenerational collaboration she sees in justice feminism. “Women from across generations and across borders and boundaries are coming together to push back against enemies that even some of the most powerful militaries can’t combat,” she said.

Today, Mahdavi said, she’s also heartened to see how different undergrounds are starting to unite to create larger change. As an example, Mahdavi cited the #BringBackOurGirls campaign in Nigeria, which was able to bring worldwide attention to the fates of 276 schoolgirls who had been kidnapped by the terrorist group Boko Maram. She also shared a lesser-known example from some of her own work on trafficking relating to women in Madagascar, also known as Malagasy women.

“These feminist networks organized from Kuwait to Switzerland to South Africa to get all the Malagasy women who had been incarcerated in Kuwait with their babies, they got them all home,” said Mahdavi. The story, which she documented in her 2016 book, Crossing the Gulf: Love and Family in Migrant Lives, did not get prominent media attention, she said. “It wasn’t on Twitter or social media but it was a great example of these transnational feminists coming together, sharing their undergrounds to get women and their children, in this case, home safely.”

Its epilogue was equally important, she continued; these same women, Mahdavi said, were able to change the policies in their home countries to make migration safer for other women.

In response to a question from Parrish, Mahdavi said that transnational feminist movements have momentum today for a confluence of reasons. “Success begets success,” she said, and feminists are watching movements around the world and borrowing strategies from one another.

While doing field work in Dubai, she recalled being heartened by seeing feminists—women and men—come together and share strategies of how to combat oppression. “That hadn’t been happening because people first of all weren’t as mobile before as they are now,” she said. They also weren’t as networked, she added.

“Look at us,” she said, referring to the event’s broadcast on Youtube, “we’ve got people coming in from all around the world listening to us which is wonderful—but this obviously couldn’t have happened three decades ago. So there’s momentum, which we’ve got to capitalize on. The case has been made. Now we’ve got to make the change.”

Parrish asked what that change would look like, and invited Mahdavi to imagine “a fully scaled transnational feminist movement.”

“It’s a world where justice is really at the heart of everything we do,” Mahdavi said. In other words, having policies both foreign and domestic that consider questions of justice at the forefront.

Transnational women’s movements have combined progress and backlash, Parrish pointed out. “There’s been a pull and a push in a negative way against these movements. Do you think people are starting to see the benefit to all?”

Mahdavi replied: “It depends what part of the world that we’re talking about. I think here in the United States we’re finally starting to see it.” She also suggested that the “triple pandemic”—the viral pandemic of COVID, the social pandemic of racism, and the climate emergency pandemic—is forcing people to rethink the paradigm we’re in.

“We need new models of leadership to get us out of this situation, and we need new ways of knowing,” she said.

Audience questions piled in for the panelists throughout the discussion. One asked which countries are at the forefront of transnational feminist movements today.

“I wish I had a crystal ball,” said Mahdavi, but if she had to guess, she would list India, South Korea, Iran and different parts of the Middle East, Nigeria, Canada, and Mexico.

Several audience members wanted to know what men can do to be better allies to women and these movements.

“Listen,” said Mahdavi. As men begin to practice “being self-reflective and saying here’s my positionality” will make a big difference.

Nearing the end of the conversation, Parrish pointed out that it’s human nature that when you rise up, you step on who’s behind you. How, she asked, can feminist movements be better at lifting up others as they rise?

“That intentionality has to be there,” said Mahdavi. “We have to remember we have to lift as we climb,” she said circling back to a point she’d made earlier in the evening about feminist leadership. “True feminist leaders, male or female or nonbinary leaders, are not going to step on people on their way up. We are going to lift as we climb.”

Send A Letter To the Editors