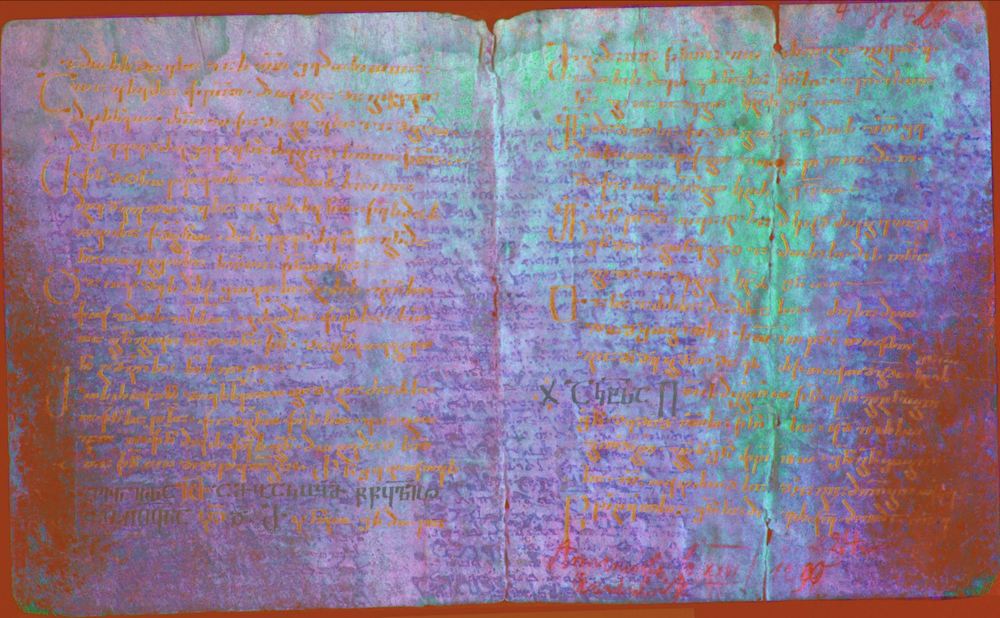

A digitally-enhanced image of a manuscript that was written over. Ms. Frag. 32, Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, Special Collections, Collegeville, Minnesota. Image used by permission.

since feeling is first

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

—e.e. cummings

As usual, e.e. cummings was on to something. We feel before we think. Words are a process built to describe—to translate—those feelings into thoughts with agreed-upon meanings. So far, so good. But feelings are anything but a zero-sum game; there is always a remainder, a residue, that most words cannot fully describe. Feelings are not mathematical, and even math has amounts left over after computation.

Feelings are more complex than the systems describing them. Sure, feelings might begin with the initial electric impulses fired from neuron to neuron within our brains, but soon enough the nuance of personal experience kicks in, way before any of us can think of the words to describe why. And when we do find the words, we tend to crop the edges, lop off the remainders that elude precise description, preferring thought packages that over time we have considered more easily digestible and translatable between us. But too often such translation sacrifices the ineffable gold of difference that resides just beyond what we choose to define.

These remainders—at least in an America that prizes straight talk and bottom lines—elude our simple expression and become trash, discarded by our baked-in moral urge to adhere to category and function, and left to blow away in the wind. And that’s OK. Even better than OK. Yes, we need clarity to build an IKEA bookcase, but not everything is IKEA furniture.

And not all of those remainders are trash.

It’s good that some of the residue resists translation. And as our world changes, some of it now feels like treasure. Our current sea of cultural consciousness shows us that meanings can slosh over definitions and other divides—and our culture is the better for it.

Otherness was once something untranslatable in polite company, but things change—and when they do, language is often found wanting. For example, binary and cisgender pronouns have given way to they/their. Of course, they/their feels and sounds awkward, precisely because the grammar is a vestige pointing to an outdated worldview. Sooner rather than later, syntax will catch up with new inventions or more relaxed meanings. Language ought to fit us—not the other way around.

It’s not hard to find examples of our idioms falling short of how we really feel. Our past heroes, who were speaking for us and fighting for our freedoms, were contending with outdated syntax in their own times, and the stakes were high. Perhaps they are our heroes precisely by nature of the way they demanded a more distinctive, edgier, and more profound picture of their identities—not just the thought, but how it really feels.

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote that “[t]he problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line—the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea.” Thankfully, we’re two decades into a new century. But reminders of old categories remain in the idioms and their long-ascribed meanings that we still use, and that still trips us up in unexpected ways. Even in the above quote, there’s that pesky use of “men” instead of people or humans. We know what Du Bois means, but it still rankles a bit. If he were alive today, I believe Du Bois would massage the knots out of his strained syntax.

Time and again in his masterly prose, you can feel Du Bois fighting against the constricting idioms of his time, describing his racial identity as

born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, — a world which yields him no self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One feels his two-ness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder. (“Strivings of the Negro People,” The Atlantic, 1897)

The cisgendered, male-centric realities of yesterday give way to new angles on such idioms today, in this case not just two-ness but triple consciousness, thanks to current thinkers redefining identity for Black and Indigenous people of color (BIPOC), transgender people, and others outside old categories.

Syntax changes because language is alive—at least as long as we are. Changes can cause irritable reactions, grumpiness, and curmudgeonly responses in the short term. But over time, my money is on multiple consciousness when speaking about race, gender, and the million other feelings that identify us.

Read this essay as a plea, or a plug, for the untranslatable in our lives. The urge to explain, to categorize and label every single thing under the sun, to amass not only data but metadata about our world and ourselves, would seem transcendent and seemingly unescapable. Yet the power of mystery remains, as difficult to detect as dark matter, emitting neither light nor energy, coexisting with what we know (or think we know), refusing to behave according to known labels or categories. And when you add it up, there is way more remainder than sum.

I would argue strongly for the embrace of the untranslatable in all things great and small. We bump up against untranslatable words when moving from one language to another and finding that we are not able to find the right word or to have its sense satisfactorily expressed. But we really don’t have to leave our own language to run up against the same sensation.

“Tradutore, traditore,” is an Italian saying than connects translation to betrayal. Perhaps we are traitors to even try to translate the feelings that outdistance our thoughts and break longstanding syntactic rules. But we have to try, and we can’t let stand the closefisted reactions of those who would ignore the residue, the remainders and the leftovers. We mustn’t be traitors to what we truly fear, desire, and keep secret.

Back to e.e. cummings. If indeed feeling is first, then the spoken and dramatic arts show us where words are not enough, where actions speak, where pictures are worth a thousand words, and where nothing (thankfully) is pure. Poets and playwrights and troubadours use the language to its fullest extent and beyond, and when they come to the rim of the well the real fun begins.

The poet Pablo Neruda knew this, writing:

Si cada día

dentro de cada noche

hay un pozo

donde la claridad está encerrada.

Hay que sentarse a la orilla

del pozo de la sombra

y pescar de la sombra

y pescar luz caída

con paciencia.(If each day

falls inside each night

then there is a well

where clarity is locked within.

One must sit on the rim

of the shadow of the well

and fish the penumbra

and trawl the fallen light

with patience.*)

There is a clarity of feeling locked within the well of shadows. Our fears, desires and secrets are our own, often invisible not only to others but to ourselves. When we use language to trawl the fallen light, we are bound to get some—but not all—of what’s there.

That’s why I, as a playwright, feature the untranslatable whenever possible. And that’s why the living body interprets best, opening itself to, and bumping up against, an immediate present; our flesh feels the pinch of limitation as well as the occasional satisfaction of an exact fit. I like it when words can’t quite comprise the feelings I’m trying to express, precisely because I need bodies on stage to add dimension and impact to the collision between meaning and what remains. When character is revealed, there needs to be more than just a psychological solution to a human problem. There is a lacuna, or lexical gap, where mystery resides and where no quantized or fully defined equivalent can be found.

Still, when faced with lacunae, I have a choice: I can fill the gap with action, movement, dance, or song. I can invent a new word to attempt to comprise and represent the remainders (Shakespeare did this many, many times). Or I can leave the gap for what it is: unfilled, missing, and open for meaning.

When I ponder it now, I realize that these are the moments when I love playwriting the most. In such moments, we are doing our soul’s work.

The untranslatable lives every day in dreams and wakefulness. We feel it when there are obstacles placed in front of what we desire, when we must confront our fears, and when we feel that our deepest secrets might possibly be outed somehow, some way. It will always be there beyond the frame of our vista, just out of bounds in the field of our lives’ play. Some feelings aren’t simply untranslated, but untranslatable, in the immediate present of our realities. But even if they can’t be rendered, they can be mined toward a new language of the future. The nuance of how we live our lives when old phrases won’t suffice is not as scary as the curmudgeons and reactionaries would have us believe. Our language is supple, and changeable. Our feelings are free, have a life of their own, and happen at the speed of light.

*The author’s own translation of Pablo Neruda’s “Si cada día cae”

Send A Letter To the Editors