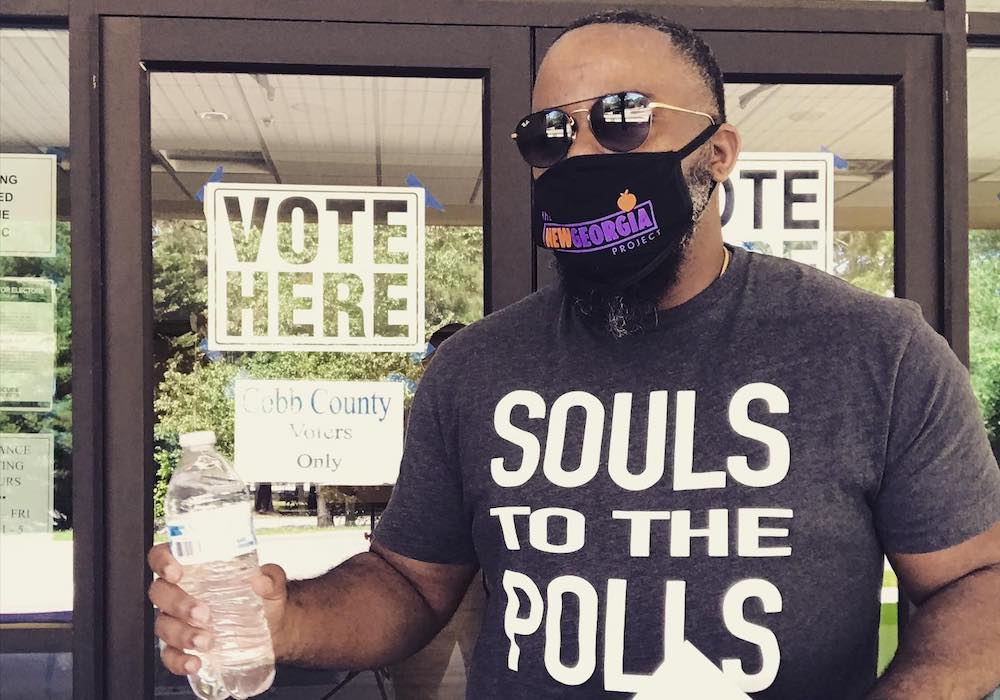

Volunteers in Georgia, including the author, have passed out water in long voting lines. Now a new law might end the practice. Courtesy of Billy Michael Honor.

Georgia has become the epicenter of the voting rights fight in the United States. The reasons for this are myriad, but include a progressive civic engagement movement in the state that captured the attention of the American public when it pulled together the votes to elect Democratic Senators Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff—and President Joe Biden. Stacey Abrams’ high-profile bid to become the state’s first African American governor, which in 2018 energized a previously unengaged group of voters who now believe a progressive wave is possible in Georgia, also placed the state’s elections in the national spotlight.

But most of all, Georgia’s notoriety is due to a series of controversial so-called “election integrity” measures put in place by the state’s Republican-run legislature. The most infamous of these is the Election Integrity Act, also known as Georgia Senate Bill 202, passed in March of this year. SB 202 is basically an assemblage of changes to the administration of voting, put in place purportedly to increase election integrity and security. The new law calls for additional ID requirements for voting by mail. It stops the practice of automatically mailing ballots to voters. It gives the state election board added power to take over any county election office for “underperforming”—giving the state board, currently fully controlled by the Republican legislative majority, power to unilaterally disqualify ballots across the state. It’s not hard to understand why handing so much power over local election authorities to any political party is so worrying.

SB 202 also includes a stunning prohibition against passing out water or food to voters standing in line. By equating this practice to electioneering, legislators turned a kind act into a misdemeanor, punishable by arrest.

Much has been said and written about the overall impacts of the law. Some, including Abrams, have called it “Jim Crow 2.0.” Others believe the bill was intended to do nothing more than appease Trump supporters who believe the 2020 general election was stolen. But there hasn’t been enough public conversation about the implications of this criminalization of kindness. Over the last few years in Georgia, as part of my work as a faith-based community organizer, I’ve recruited more people of faith to pass out water, snacks, ponchos, and crossword puzzles to Georgia voters standing in long lines than anyone else; some 300 volunteers across the state, from Savannah to Macon to Rome, have participated in this act of civic kindness. That’s why it is particularly heartbreaking and infuriating for me to see this prohibition become a law in our state.

I began showing care to voters in long lines in 2010, when I was the pastor of an Atlanta congregation that also happened to be a polling precinct. On election days, lines to get into the fellowship hall where people voted sometimes stretched down the church’s long educational wing hallway onto the outside sidewalks. Whenever that happened, the church staff and I passed out water and offered chairs to voters. We also passed out umbrellas when it rained. Obviously, this was not our responsibility as a polling site. But I had experienced the horrors of Georgia’s long voter lines when I waited 8-and-a-half grueling hours to vote in 2008’s general election. I’ll never forget arriving at my polling place at 8:30 a.m., thinking I’d be in and out in a couple hours max, and ending up in a several hour battle to cast my vote, with only water from a public fountain to drink and candy from a nice lady next to me in line to eat. From then on, I saw it as my duty to help make the process more bearable.

It’s worth noting that the main reasons for these long lines in our state are poor election administration and intentional neglect. Georgia has experienced rapid population growth, but the secretary of state and boards of elections have failed to add more polling places. In fact, they’ve actually sought to close polling sites in some of these high volume and under-resourced precincts—many of which are in Democratic-leaning, non-white communities. This is why many see long lines as the result of GOP voter suppression.

Whatever the cause of the long lines, many people have stepped up to make standing in line easier, as a matter of humanitarian necessity. I started to expand my efforts in 2018, as director of faith and civic organizing for the New Georgia Project, a nonpartisan organization founded by Abrams and led by noted civic leader Nse’ Ufot, that has registered and engaged Georgians since 2013. I built up a large network of faith leaders who provided care to voters all over metropolitan Atlanta. Clergy showed up at crowded, overwhelmed polling precincts to pass out water, snacks, ponchos, fans, and books. We instructed volunteers to pass out only comfort-related resources, and to tell voters nothing more than, “Thank you for coming.” Talking about candidates, political platforms, or parties was always strictly prohibited.

By the 2020 elections, our voter care program was well-known and well received. We partnered with organizations and prominent ministers from several denominations to expand it, sending hundreds of people of faith to the polls to provide these resources for Georgia voters. We conducted several trainings for volunteer poll chaplains in Georgia, and in several other states as well. People who attended our trainings never heard anything remotely close to electioneering. Instead, we emphasized that this was a faith-inspired, nonpartisan act of civic engagement. To my knowledge none of our volunteers, or any other faith-based groups, ever violated this principle.

Now that SB 202 is law, care providers will have a much harder time helping voters in long lines. Undoubtedly precinct managers and state election officials will be zealous to enforce the new prohibitions. They may try to drive voter care providers farther and farther away from election lines, overpolicing polling sites and causing unnecessary conflict. All this happens as Atlanta, the state’s largest city, prepares for a hotly contested mayoral election this November and statewide elections in 2022 that will feature a U.S. Senate race between Warnock and a Republican challenger—and, most likely, a gubernatorial rematch between Abrams and Gov. Brian Kemp.

With blockbuster elections like these around the corner, you can see why temperatures are rising in our state around voting rights. The stakes are high, with lasting implications for state and national politics! But there are also moral implications at stake. If people of goodwill can’t show compassion to fellow citizens in onerous voter lines, what does that say about the moral state of our society? Has political identity and beating the other side become more important than showing common decency? And what are people of faith to think about a system that would rather jail people for committing faith-inspired acts of kindness than fix an obviously broken system?

To be clear, I don’t think SB 202 was intended to target clergy and people of faith. We are simply unintended collateral damage in a broader voter suppression effort. I believe the originators and supporters of this law view all organized efforts to give relief to voters in long lines to be part of the Georgia Democratic Party turnout machine—efforts that don’t serve their interests as Republican lawmakers. As a result, they see no problem with criminalizing a benign act of civic kindness, without taking time to understand the citizens of goodwill it will negatively impact. They reply that groups like mine can still hand out water 150 feet away from the polling precinct. The problem with that rule, which already applies to partisan groups at polling sites, is that some polling officials bend the rules, extending the boundary well beyond 150 feet if they so choose. What’s more, once voters are in line they cannot step out to receive resources without losing their place. Effectively, we can no longer help them.

Despite my disappointment I’m encouraged by the response of the faith community to what amounts to a war on kindness. Many leaders who have passed out water to voters in long lines in the past, such as longtime activist Pastor Timothy McDonald, are vowing to continue the practice in coming elections as an act of civil disobedience. Pastor McDonald and the Concerned Black Clergy of Atlanta have also joined with Bishop Reginald Jackson of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and a group of ministers in Dekalb County (the state’s largest predominantly-Black county) to form a coalition that’s calling for boycotts, public demonstrations, and legal action in resistance to the new voting law. Others, like myself, are focusing our efforts on putting public pressure on the federal government to intervene and stop this discriminatory and suppressive new law. The Department of Justice’s decision to sue the state of Georgia over its voting laws may be a sign that our efforts are bearing fruit. Regardless of what happens, people of faith will not soon forget how their efforts to show compassion at the polls were attacked and maligned for petty partisan gain.

Send A Letter To the Editors