Patrick Soon-Shiong is the second-wealthiest Angeleno with a net worth of $21.8 billion. Courtesy of NHS Confederation/ Flickr CC BY 2.0

If you were trying to understand the economy of Los Angeles County during the first half of the 20th century—the period in which L.A. emerged as a modern metropolis—you’d do well to scrutinize the business interests of one man: Harry Chandler.

Not that you could ever peel back all the layers of Chandler’s empire. “He operated in a whirlwind of activity … setting up numerous dummy corporations and secret trusts,” Robert Gottlieb and Irene Wolt explained in Thinking Big, their epic account of the making of Southern California, as seen through the history of the Los Angeles Times, where Chandler served as publisher from 1917 until 1944. On his deathbed, they noted, Chandler was said to have had his papers destroyed.

Nevertheless, even just a handful of the most visible pieces of Chandler’s domain would tell you plenty about the industries that hastened the place’s heady growth 100 years ago: aerospace, autos, agriculture, oil, shipping, movies. Chandler—the wealthiest man in L.A. and one of the dozen wealthiest anywhere—had a hand in each of them.

He arranged financing for Donald W. Douglas, who began designing aircraft in the back room of a barbershop on Pico Boulevard in 1920, and within a few years, was putting together military planes from a Santa Monica factory. Chandler also invested in and became a director of Goodyear, which cranked out as many as 15,000 tires a day in downtown Los Angeles, helping to usher in the region’s signature car culture.

To the north, straddling Los Angeles and Kern counties, workers at Chandler’s Tejon Ranch farmed and tended cattle across a rugged expanse about 40 percent the size of Rhode Island. To the south, along the line dividing Los Angeles and Orange counties, he and his partners sank more than 100 wells and pumped 75,000 barrels of crude from the ground every day. Chandler assisted his father-in-law, Harrison Gray Otis, in bringing the port to San Pedro and formed the Los Angeles Steamship Company.

And he left his mark on show biz as well: The promotional sign at one of his myriad real estate developments was truncated from HOLLYWOODLAND to HOLLYWOOD in the late 1940s.

Today, no one person could possibly match Chandler’s reach into every corner of L.A. commerce. The barons of our age tend to be more narrowly focused in their endeavors. But if you looked at, say, the 10 men and women whom the Los Angeles Business Journal deemed the richest in the area in 2020, you would peer through a pretty good window into what currently propels the county economy—a $700-billion-a-year juggernaut that, were it a stand-alone nation’s, would rank as the 22nd biggest on Earth, larger than Poland’s or Sweden’s.

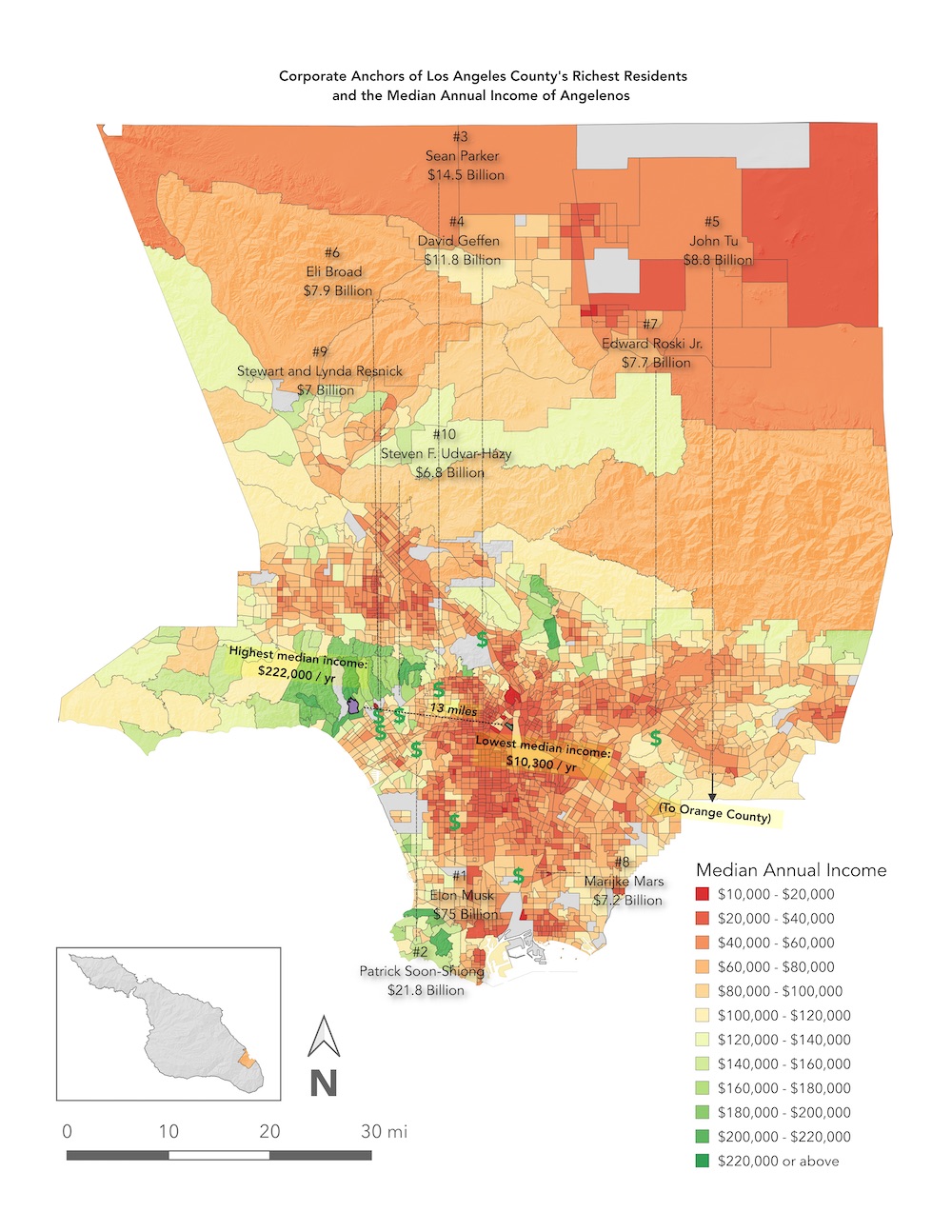

The map indicates the location of the business from which at least some of the richest Angelenos’ wealth is derived or where they have a presence via a corporate headquarters, factory, or other facility. Map by Ezra Rawitsch.

To be sure, no 10 people can tell the full story of a labor force of about 5 million. Zeroing in on the uber-rich can also obscure the daily hardships of L.A. County’s people, more than 20 percent of whom live in poverty. One in four workers in the county earns less than $15.60 an hour, or under $33,000 a year, if they’re full-time. As of early 2020, some 66,000 people in the county were homeless.

Yet, taken together, these 10 billionaires do reflect an awful lot. Most of them are self-made, emblematic of the county’s entrepreneurial spirit. They touch all 10 industries singled out by the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation as central to the business landscape: aerospace and defense; marketing, design, and publishing; food manufacturing; trade and logistics; hospitality and tourism; information technology; entertainment and digital media; fashion, apparel, and lifestyle; bioscience; and advanced transportation.

Steven Udvar-Házy is 10th on the Business Journal’s roster of the wealthiest Angelenos, boasting a net worth (assets minus liabilities or, more plainly, what you own minus what you owe) of $6.8 billion. Dubbed by Reuters “the unofficial godfather of the civil aviation market,” Udvar-Házy made his money leasing planes to the airlines. But he is part of a broader sector that has two very different sets of customers: commercial carriers and government. In this way, the Hungarian native, whose family fled to the United States in 1958 from their Soviet-occupied homeland, showcases an industry that has a far smaller footprint in L.A. County than it did during the Cold War, but remains significant.

In fact, all in all, it’s fair to say that the requiem for aerospace in the region has been exaggerated. In 1990, after the Berlin Wall fell, Los Angeles County had more than 130,000 aerospace manufacturing jobs. These days, that number sits at around 40,000. In between, some industry titans merged or went out of business. Northrop Grumman ditched its Century City headquarters for suburban D.C., and Boeing sold off the mammoth Long Beach plant where it once assembled C-17 cargo planes for the Air Force.

But the industry’s total payroll has held pretty steady for more than 15 years now, with some segments (such as jet engines) shrinking and others (like missiles and space vehicles) booming. All of the big guns still have facilities here, from Boeing in El Segundo and Northrop Grumman in El Segundo and the Beach Cities to Lockheed Martin’s legendary Skunk Works in Palmdale and Elon Musk’s SpaceX in Hawthorne. And many other aerospace suppliers fly below the public’s radar but are essential: Paragon Precision in Valencia, Airmark Plastics in Azusa, Dytran Instruments in Chatsworth, to cite but a few. As for Udvar-Házy’s current company, Air Lease, its main offices are in Century City (as was International Lease Finance, the firm he co-founded in 1973 and later unloaded, turning him into a billionaire).

If it takes a certain kind of nerve to imagine that humans should soar through the heavens in a metal tube, it takes a wholly different kind of audacity to believe that pomegranate juice can be sold, in the words of the New Yorker, “as an antioxidant-rich miracle food that might improve cardiovascular health, battle prostate cancer, even prevent Alzheimer’s disease.” Ninth on the Business Journal list, with a net worth of $7 billion, is a couple who pulled off that marketing miracle: Stewart and Lynda Resnick. Their Wonderful Company’s 150,000-plus acres, planted with 15 million almond, pistachio, pomegranate, and citrus trees, are spread across the southern San Joaquin Valley, up and over the Tehachapis from their Beverly Hills estate.

But their genius—Lynda Resnick’s genius, really—is in cultivating brands, which also include Fiji Water and Teleflora. At times they’ve gone too far. Federal regulators at one point made the company pull some of its ads after questioning the scientific rigor behind claims that drinking its POM Wonderful pomegranate juice could “cheat death” and mitigate erectile dysfunction. Nevertheless, there is no denying their knack for swaying consumer behavior. “Creative collisions occur where industries overlap, driving new business concepts,” the county’s economic development officials tell us. In a nutshell (not to mention a seedless mandarin and the orb of a pomegranate), that is what the Resnicks have done. They “have wedded the valley’s hidebound farming culture with L.A.’s celebrity culture,” the journalist Mark Arax has written. “Their crops aren’t crops but heart-healthy snacks and life-extending elixirs.”

Beyond the marketing, the Resnicks represent another of the county’s key industries—food manufacturing. So does the eighth richest person in L.A.: Marijke Mars. Worth $7.2 billion, she inherited a stake in her family-owned company, Mars Inc., maker of Snickers and Twix candy bars, Wrigley gum, Uncle Ben’s rice, Dolmio pasta sauce, Whiskas cat food, Pedigree dog food, and much more. After graduating from college, she went to work at the company’s Kal Kan division in Vernon. Mars also owns the organic food producer Seeds of Change in Rancho Dominguez, an unincorporated county community tucked between Compton, Long Beach, and Carson.

Mars is hardly the only major industry player in the county. Dole, the fruit and vegetable giant, is headquartered in Westlake Village, Sunkist Growers in Valencia, Nestle USA in Glendale, Beyond Meat in El Segundo. In all, about 35,000 people in L.A. County work in food manufacturing, a particularly vast and varied field, befitting a megalopolis where more than 220 languages are spoken.

Here’s a tiny taste: You can find Saigon St. Foods in Los Angeles, Graciana Tortilla Factory in Sylmar, Otafuku Foods in Santa Fe Springs, Pacific Spice in Commerce, Jericho Foods in Sun Valley, Soyfoods of America in Duarte, and Huy Fong Foods’s Sriracha hot sauce factory in Irwindale.

Whether it’s hot sauce or Hot Wheels, all of it has to be stored and shipped. Edward Roski Jr., number seven on the rich list with a net worth of $7.7 billion, made a mint by meeting this demand. His Majestic Realty, started by Roski’s father in 1948, has developed warehouses and distribution centers in the City of Industry, as well as in counties neighboring L.A. Majestic’s multi-state, 82-million-square-foot portfolio includes hospitality, office, and retail properties. But it’s the warehouses that Roski seems to relish most. “What I like about industrial buildings is that they supply the things every American needs, every day, for their lives,” he once said. “We really help keep America functioning.”

The hub of L.A. County’s logistics industry are the neighboring ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, situated along San Pedro Bay. The two top handlers of cargo in the country, they were moving a combined $2 billion worth of stuff in and out every day before the coronavirus roiled the global economy, enough activity to generate about 200,000 jobs locally and 1 million across the region. All told, the ports normally traffic in more than 275 million metric tons of cargo annually—equivalent, the trade publication FreightWaves has pointed out, to 173 million cars or 25 billion watermelons—and stand as the nation’s gateway to Asia.

For his part, Roski also has ties to another crucial industry in the county: hospitality and tourism. He is a co-owner of the Lakers and Kings and the arena in which they play, Staples Center, which (again, in non-COVID times) draws more than 4 million people a year for sporting events, concerts, and more. Many of those who attend are locals, but a fair share who flock to Staples or the entertainment complex right next door, L.A. Live, are out-of-towners. The same is true for the county’s many other cultural attractions, whether highbrow or low: Walt Disney Concert Hall, the Hollywood Walk of Fame, Universal Studios, the Getty Center, and so on and so forth. Pre-pandemic, more than 50 million people visited greater Los Angeles every year, pumping more than $30 billion into the county economy and supporting 240,000 jobs.

Among the most popular destinations is the Broad, the contemporary art museum Edythe and Eli Broad opened in 2015 on Grand Avenue in Los Angeles. Eli Broad, who died in April, was the sixth richest person in L.A. in 2020 with a net worth of $7.9 billion. On top of the art scene, Broad put his fingers into all sorts of issues—charter schools, the revival of downtown L.A., medical research, gun control—and came closer than anyone to being the Harry Chandler of the later part of the 20th century and the early part of the 21st.

Broad got super rich by starting two businesses that became Fortune 500 corporations: financial services provider SunAmerica (sold to American International Group in 1998 for $18 billion), and before that, homebuilder Kaufman & Broad. The company, now called KB Home, has erected thousands of dwellings across Southern California and throughout L.A. County—including in Sylmar, Paramount, Santa Clarita, Lancaster, and Woodland Hills. This catalyzing of sprawl remains controversial. In his seminal book, City of Quartz, Mike Davis excoriated Kaufman and Broad for practicing “the ecology of evil.”

The fifth wealthiest person on the Business Journal list, John Tu (net worth: $9.7 billion), offers a twist: He lives in Los Angeles County (Rolling Hills), but his company, computer memory and storage products maker Kingston Technology, is located in Orange County (Fountain Valley). That in of itself says something about how the “L.A. County economy”—the flow of goods and services, talent, and ideas—doesn’t stop at the borders on a map. Indeed, many analysts prefer to measure the economy across the entire Los Angeles Basin—L.A., Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties. Roll them all up, and annual output hits $1.3 trillion. That’s more than Mexico or Indonesia.

In terms of tech, when people use the moniker “Silicon Beach” to describe the locus of technology companies in the area, they sometimes loosely lump together L.A. and Orange counties. On the Los Angeles County side, much of the action is unfolding at 500-plus enterprises concentrated along the coast. Snap, the social media company, began in Venice and then moved to Santa Monica. Facebook has operations in Playa Vista and Northridge. Google employs thousands in Venice and Playa Vista, occupying the immense hangar where Howard Hughes built the Spruce Goose, his wooden airplane, in the 1940s. The company has been planning to take up a third campus in Los Angeles, inside a renovated Westside Pavilion shopping mall, in 2022. Meanwhile, smaller tech firms abound. Appetize, in Playa Vista, created a cloud-based platform that processes point-of-sale transactions. Nativo, in El Segundo, is an adtech firm. Headspace, in Santa Monica, makes a meditation and mindfulness app. Wevr, in Venice, is a virtual reality company.

About 40,000 people in L.A. County manufacture hardware and electronic products. Another 40,000 or so design computer systems and sell related services, state employment statistics indicate. Taking a more sweeping approach, one study tallied 260,000 information and communication technology jobs in the county. It got there by counting occupations that might not typically be thought of as “tech” per se, including the digital production and computer animation work being done in Hollywood.

If you were cheeky, you might say that Tu himself is also part of the entertainment industry because, in his free time, he plays the drums in his band, JT and California Dreamin’. Yet the fourth-richest person in L.A.—David Geffen—is a better way into Tinseltown.

A native New Yorker, Geffen has credited his mother, Batya, with teaching him the ins and outs of business. In her case, the business was undergarments, which she sold from the family’s house in Brooklyn under the name Chic Corsetry by Geffen. By default, that makes her son more connected than anyone on the Business Journal’s list of L.A.’s most affluent to fashion and apparel—another pillar of the county economy. Although an exodus of sewing machines to cheaper locales abroad has reduced industry employment to about a quarter of what it was 25 years ago, L.A. is still home to up-and-coming designers; established companies such as Lucky Brand, Nasty Gal, Revolve, and Reformation; and a designated fashion district downtown.

Geffen amassed his own fortune—$11.8 billion, as the Business Journal has it—by peddling content, not corsets. The music and movie mogul co-founded Asylum Records in 1970 (where he signed Jackson Browne, Linda Ronstadt, and Joni Mitchell) and in 1980 founded Geffen Records (whose stable included Donna Summer, Elton John, Cher, and Guns N’ Roses). He financed a string of hit movies, including Risky Business, Beetlejuice, Little Shop of Horrors, and Interview with the Vampire. In 1994, he co-founded the film studio DreamWorks with Steven Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Of course, no business is more identified with Los Angeles than entertainment. For locals, it can feel ubiquitous. More than 100,000 people work in motion pictures and sound recording in the county. Some 250 film stages are scattered around greater L.A., from Lakewood to Castaic, from Santa Monica to Sherman Oaks. Icons like Disney and Warner Bros. in Burbank, Paramount Pictures in Los Angeles, Sony Pictures in Culver City, and Universal Music Group in Santa Monica have a huge presence.

But over the past 20 years, new entrants have upended how we watch and listen to our favorite actors and artists, and now they’re whipping up their own content. Where the tech industry ends and entertainment begins is increasingly unclear, especially as the disruptors gobble up real estate all over L.A.: Netflix in Hollywood, Amazon Studios and Apple TV in Culver City, Hulu in Santa Monica, YouTube in Playa Vista.

These streaming media companies might never have gotten so far so fast had it not been for the gumption of the third-wealthiest person in L.A.—Sean Parker. He was 19 years old when he co-founded Napster in 1999. Accused of enabling mass piracy, the online file-sharing company was shut down two years later, but not before it pushed the music business and, ultimately, all of entertainment into the digital age.

Parker’s $14.5 billion in wealth stems from subsequent ventures; he was part of Facebook’s founding team and was an early investor in Spotify. In 2016, it was disclosed that he was planning a movie-on-demand service called the Screening Room, which theater chains worried would undermine their business model. The scheme subsequently faded away. But then Parker revived the West Hollywood company in 2020, rechristening it SR Labs.

The second-most well-to-do person in L.A., Patrick Soon-Shiong, checks a few boxes. In 2018, he purchased the Los Angeles Times, vaulting him to the fore of the publishing industry. He also owns 4.5 percent of the Los Angeles Lakers and a real estate investment company, which has been buying up properties in El Segundo. But the bulk of his $21.8 billion in wealth is from another of the county’s most prominent industries: biotech. Nine years after its founding in 2001, he sold Abraxis BioScience for $2.9 billion. His current corporate umbrella in Culver City, NantWorks, includes various entities working on cancer treatments.

NantWorks is one of about 100 bioscience companies in the county. There are also more than 400 medical device and diagnostic equipment makers, all buoyed by a large network of public and private research institutions, laboratories, and biomed incubators. Altogether, when you toss in everyone from computer systems analysts to phlebotomists, an estimated 80,000 people in L.A. County work in the industry.

That leaves but one final type of business—advanced transportation—and the No. 1 person on the Business Journal’s list, Elon Musk, to complete the county’s economic portrait. Although Musk’s electric vehicle company, Tesla, doesn’t manufacture anything in the area, it is in many respects the standard-setter for an industry that is flourishing locally, with about 120,000 workers across Southern California. Rival EV maker Fisker is in Manhattan Beach, and the startup Canoo is in Torrance. Proterra builds electric buses in the City of Industry, as does BYD North America in Lancaster.

Truth be told, Musk, who moved to Texas at the end of 2020, shouldn’t even be part of the discussion anymore. On his way out, he took a parting shot, suggesting that California had been “winning for too long” and had become “a little complacent, a little entitled.”

Whether such criticism is warranted or not, Musk certainly made the best of it while he was living in Bel Air. The Business Journal put his wealth at $75 billion. By the end of 2020, with Tesla’s share price having risen sharply during the final months of the year, Bloomberg said he was worth $170 billion, making him the second-richest person in the world. (He’d ascend to become the richest of all in 2021, though he and Jeff Bezos can always go back and forth depending on the stock market’s daily gyrations.)

Besides, no matter where he is, Musk will forever be tied to the business of L.A. In addition to the aforementioned SpaceX, he was the inspiration for Robert Downey Jr.’s portrayal of Tony Stark in the Iron Man movies. And if you want to stretch, you can also link Musk to another portion of the entertainment industry. After a porn film was shot in a moving Tesla in 2019, Musk tweeted: “Turns out there’s more ways to use Autopilot than we imagined. Shoulda seen it coming.” It’s a good reminder that, despite being buffeted by a deluge of free online porn and regulations regarding condom use, the San Fernando Valley is still the heart of adult movie making.

And yet, other aspects of the L.A. economy are far more obscene. Several years ago, a group of scholars reported that white households in the county had a median net worth of $355,000. For African Americans and those of Mexican heritage, it was $4,000 and $3,500, respectively—in either case, less than the average amount that Elon Musk’s wealth increased every second of 2020.

Send A Letter To the Editors