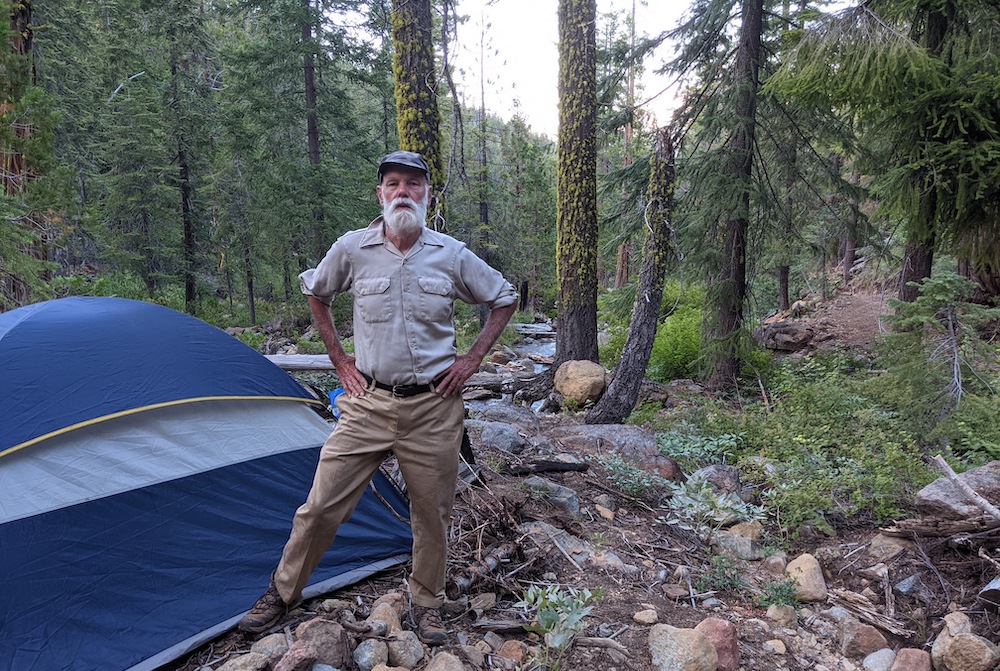

On the Sisson-Callahan Trail, near the North Fork of the Sacramento River. Photos by Todd Holbrook.

The great outdoor adventurer John Muir—who had skipped over glaciers in Alaska, surfed an avalanche, and gleefully rode a wildly swaying tree in a storm in the Sierras—lay in a hotel bed strewn with wildflowers. He gazed through the window at the majestic sight of Mount Shasta.

He had nearly died on the summit of that mountain the night before. A fierce blizzard had set in after he and mountain guide Jerome Fay reached it. A blinding deluge of snow obscured their route back, making a descent impossible.

They survived by lying on their backs, just below the summit, on a bank of “fumaroles,” fissures of hot gases escaping from the depths of the volcanic mountain.

As Muir later described it, the two men suffered “the pains of a Scandinavian hell, at once frozen and burned.”

But they survived, and by 4:00 the next afternoon had returned to the hotel and tavern operated by Justin Hinckley Sisson at the base of the mountain, near the present-day town of Mount Shasta.

Muir probably didn’t waste much time before collapsing in his bed. It was Sisson’s daughters who welcomed him back the next morning by spreading wildflowers on it.

I call this mountain region my home and enjoy exploring its trails—and its history of fascinating characters like Muir and Sisson, and stories of courage, near-death, and resourcefulness under extreme conditions. It is like reading one long adventure novel with a thin plot.

Justin Sisson himself was a notable figure, a native of Connecticut, a college-educated schoolteacher who reinvented himself when he came out West, becoming a proficient hunter, fisherman, and mountain guide—and successful innkeeper. “He knew more of the secrets of Mount Shasta than any living man,” said the San Francisco Chronicle in his 1893 obituary.

Sisson’s hotel is long gone, but you can follow the route Muir and Fay took up the mountain to the place, still known as Horse Camp, where they dismounted from their horses and continued on foot toward the summit. If you keep going to the top, you can see those fumaroles, but be aware that the weather up there can change drastically from one hour to the next. You don’t want to spend the night on them.

Recently, I did a walk on another historic trail, the one used by the horse-drawn freight wagons that supplied Sisson with the wines, liquors, and other items from San Francisco that kept his tourist mecca stocked and well-lubricated. (As many as 70 guests at a time could be accommodated in his dining hall.)

The route we followed is still known as the Sisson-Callahan Trail. Back in the freight-hauling days, it was a spur of the main wagon route that ran from the Bay Area to Oregon. The 55-mile spur started at a tiny outpost, a hotel and store, run by a rancher named M.B. Callahan.

I hiked the Sisson end of the trail, the last 10 miles, with a friend from Redding, Todd Holbrook, a search-and-rescue guy who has spent the last couple of decades finding lost hunters and hikers in the wilderness. As it turned out, we needed his skills to get us through a few places where the trail disappeared in the tall grasses of lush meadows.

For the most part Sisson’s trail goes through the canyon carved by the North Fork of the Sacramento River. Much of the trail runs high above the streambed, but there are also some stretches where it drops down right alongside the stream. Use your imagination, and you can picture thirsty horses straining at their reins, slurping a welcome drink after the long pull from Callahan.

Trails like this one, and the route up to the summit, offer us a fourth dimension, that of time and past human experience, whether it’s Muir’s near-death on the Mount Shasta summit or the more prosaic tradition of hauling goods along what is now a scenic hiking trail.

Muir’s account of his night on Mount Shasta, published in 1877 by Harper’s New Monthly magazine, is more than a great adventure story. By enriching his tale with the graceful touches of a poet and philosopher, Muir made it an adventure story for all time, embedded forever in the fourth dimension of our mountain region.

Those stories take us to the very beginnings of recreational tourism, still a vital engine for California’s remote regions, including ours. If you were to do more time-traveling and planted yourself in front of Sisson’s Hotel in 1870 to watch the decades pass, you would see the rough narrow road in front of you become a stagecoach route, with passengers dropped off right at the front door. A few decades later they’d be getting off at a nearby railroad station.

Today the original site of the old hotel is sandwiched between a two-lane frontage road known as “South Old Stage” and Interstate 5. Tourists nowadays flock to the half-dozen motels and many Airbnbs on the other side of the freeway, some of them grabbing ice picks and following the path of John Muir and Jerome Fey toward the summit.

On that night atop Mount Shasta, lying on a bed of hissing gases, Muir calmly drew out his magnifying glass and examined the “exquisitely perfect” rays of the snowflakes on his sleeve.

His thoughts soared beyond the pain and suffering of a “Scandinavian hell” and out into celestial regions that distracted and comforted him with their dazzling beauty. Despite the swirling snow above him, he had a good view of the night sky and marveled that “the mysterious star clouds of the Milky Way arched over with marvelous distinctness.”

“Every planet glowed with long lance rays like lilies within reach,” he noted.

Send A Letter To the Editors