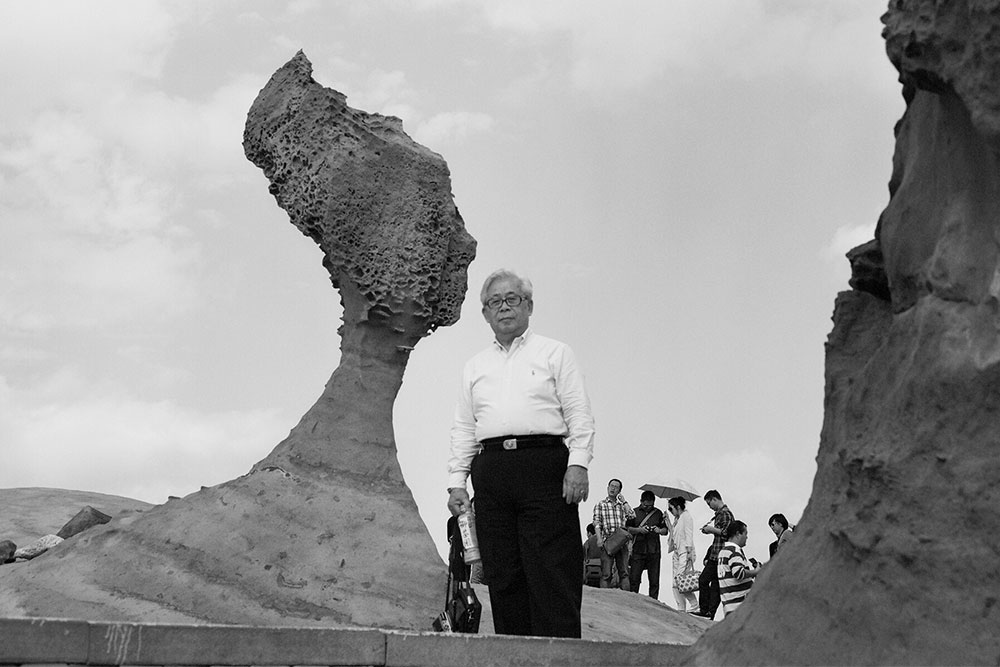

The author’s father in 2012, mimicking his earlier pose at Queens Head Rock. Courtesy of Shin Yu Pai

I was hiking the Port Orford Heads State Park on the coast of Southern Oregon this summer when I realized how closely the rock formations and coastline resemble the rugged geology of my parents’ native Taiwan. These similarities brought back memories of my trips to the country, and made me miss my friends and family overseas. By June, lacking enough shots for its 24 million citizens, the country, once seen as a COVID success story, was forced to institute lockdowns and close public spaces. Due to the pandemic and the nation’s vaccine shortage, it may be many more years before I can safely return to Taiwan to see loved ones.

When I chatted on the phone with my father in California weeks before my trip to Oregon, he said that the roll-out overseas, as reported by friends, was chaotic. I could hear the frustration in his voice, and concern for those close to us. People with money and means were vaccinated, while our friends and family who are teachers continued to wait patiently for their shot. I began regularly scanning the global news headlines for public health updates, lingering over relatives’ social media postings, and direct messaging my cousins to get a read of the temperature on the ground.

As an American-born Taiwanese, it took me 20 years and five visits to develop my own relationship to Taiwan. After my first visit in 1998, I went back over and over again to better understand how Taiwan, an island that has continually been occupied by outside presences, has its own unique character as a country, and how all of this has shaped my parents’ identities, and in turn, my own.

Before my first visit, I knew Taiwan through photographs. Nearly 20 years passed between my father’s departure from Taiwan and his return to his hometown of Chingshui in the 1990s to make offerings at his parents’ gravesites. I was in high school at the time, and when he came back home to Southern California, he brought video footage of Chingshui and photographs of our living family members. I saw images of the ramshackle remains of the Japanese colonial-style home where my father grew up, and a black-and-white image of the rock-lined, communal washing pool where my grandmother took my father as a child to clean clothes for the family. In other photos, I saw the village columbarium and its urns filled with ancestor bones ready to be buried underground. These images came to hold emotional memories for me in photographs long before I ever set foot on Taiwanese soil.

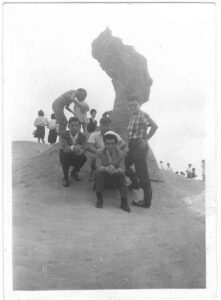

Snapshot of the author’s father (wearing a cardigan sweater) at Queen’s Head Rock. Courtesy of Shin Yu Pai

During my first visit home in 1998, my cousin Paula pulled out a box of black-and-white snapshots I’d never seen before—images from my father’s young adulthood. A series of pictures captured my father and his third eldest brother, who gave me my Chinese name, picnicking on a beach with friends. My father wore a cardigan sweater over a button-down shirt and dark pants, while resting an umbrella over his shoulder. Two photos stood out. One is a candid image of the scene someone snapped before it was done being composed. My father, his brother, and their friend stand looking at the camera before they are fully arranged, paused in a moment of time as throngs of tourists, and even a small child in the arms of a visitor, crowd the frame. And then there was the final photo in the pile, in which the young men gaze steadily into the camera’s lens while posing in front of a distinctive rock shaped like a woman’s profile. Fascinated by the image of the pockmarked rock, I asked my relatives about its origins. I was told that the photo had been taken in Yehliu Geopark, and that the formation was called Queen’s Head Rock.

By the time I got to Yehliu to explore the headlands where my father walked, it was 2006. My cousin drove me to the northern coast to visit the popular geological park. In the years since my father’s visit, a wooden boardwalk had been built to redirect visitors and flow traffic away from Queen’s Head Rock to other hoodoo stones on the promontory. But on this day, the promontory was fairly unpopulated, and we didn’t have any difficulty moving from one stone feature to the next. Many of the rocks have whimsical names like “Fairy Shoe,” “Beehive,” and “Sea Candles,” though some of the names are quite a stretch of the imagination, and it takes some creativity on the viewer’s part to see the resemblance. But the connection between “Queen’s Head Rock” and its formation was unmistakable. Its mushroom-shaped form tapered into a neck-like structure—thinner now due to erosion than it was in my father’s photos—that radiated outward in the shape of a human head. The back of the head was elongated as if the woman wore a headdress, which made the rock feel almost Egyptian in its form.

I returned to see Queen’s Head Rock a second time, when my husband came from Texas to join me in Taiwan. I wanted him to see and know a place in my family history. We took photos in front of the personal landmark, and I filed them away with the vintage image of my dad that I’d digitized on my computer.

Then, in 2012, I accompanied my father back to Taiwan to visit relatives and to revisit an outlying island where he had carried out his military service. When my dad’s friends suggested a day trip up to Yehliu, I readily agreed to a third visit, as I wanted to photograph my father next to Queen’s Head Rock, as he had posed nearly 50 years before.

Ever since my years as a student at the University of Washington, the work of John Stamets, who taught at the university before his death in 2014, has continued to influence my eye as a photographer, even though I never studied with him personally. Stamets specialized in architectural photography and a method called “rephotography” in which he recreated historical scenes of past and present pictures. Through these images of then and now, the image-maker registers the evolution of a changing environment and the people in it.

When we arrived at Queen’s Head Rock in 2012, much had changed. To protect the site, the park had installed a ring of smaller stones around Queen’s Head Rock, so that visitors could no longer get close to her. And unlike my past visits, this time, hundreds of tourists crawled the headlands, queuing up on the wooden boardwalk for their turn to take a selfie. My father complained bitterly about the heat as he progressed through the line, but dutifully posed as I asked when it was our turn to take a photograph. A park attendant blew his whistle to signify when our time with the rock was over. Keep moving!

The author and her father with friends, Queen’s Head Rock. Courtesy of Shin Yu Pai

I already knew the images would not be the same, though I snapped photos of my father with his friends as well as pictures of him standing alone near the rock. That’s all I could manage before we were waved off the boardwalk. My father was too overheated to entertain posing as he had five decades before, and we were too pressed for time for me to properly compose the shot to mimic what had been photographed before. I felt weepy at being rushed off, disappointed that my father couldn’t understand why the act of photography in that moment should matter anymore than the usual tourist selfie. Traveling with my father is often fraught with unmet need and conflicting agendas. But I had imbued that unrealized photo with the qualities of an imaginative touchstone, a document of our relational continuity and evidence that my father and I were there together, walking through different histories and reaching across time and place to meet one another in the present.

Entering a John Stamets photo is a bit like going back in time. The eye and mind naturally look for the places of continuity, no matter what has changed in the foreground. As viewers, we gravitate toward what has stayed the same, while recognizing what has been lost forever, most often through human intervention. These images can be surprising, enduring, and an exercise in documenting something that by definition often eludes the eye: absence. When I look at my own archive and the places that I have revisited time and time again, I notice that a tree is missing, a pergola is gone, or that an iconic stone has been worn down by the decades.

Gazing out at the ocean from the western most point in the State of Oregon, I thought about my last remaining uncle, my cousins, and their children quarantining at home. I pictured, too, the marine debris from Japan’s 2011 tsunami that washed its way all the way to the Pacific Coast. These distances of place and time both are and aren’t as far as they seem. Sea water and wind conditions will continue to batter the geological formations at Yehliu, causing the neck of Queen’s Head Rock to continue to thin. Queen’s Head Rock will become so fragile that it finally breaks, or crumbles as a result of an earthquake or human touch. I grieved its impermanence as I stared at the sea stacks along the Pacific Coast, feeling the distance between.

Send A Letter To the Editors