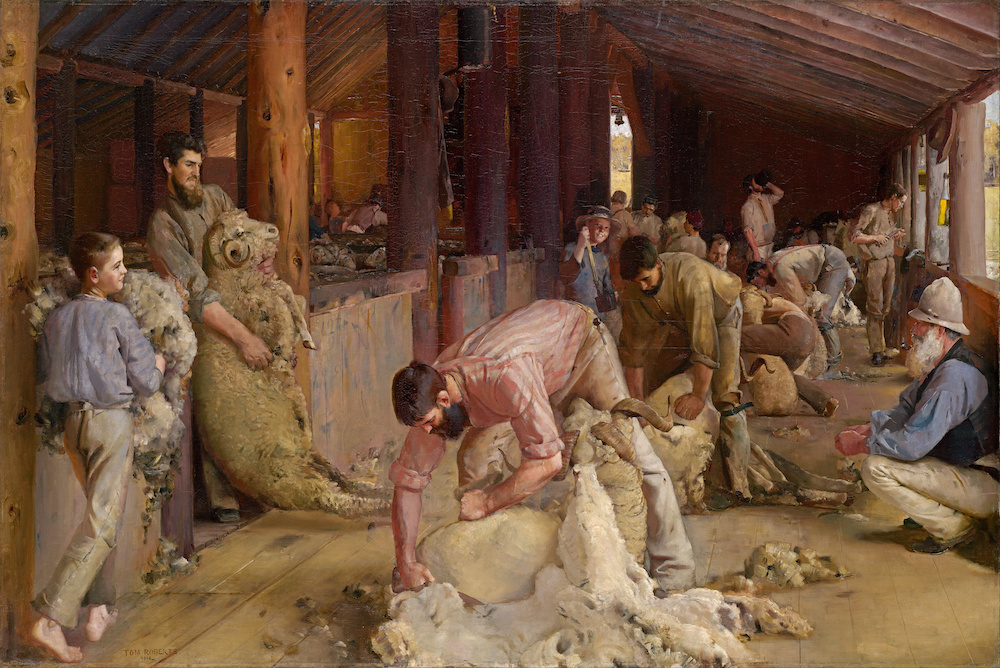

“Shearing the Rams,” oil painting by Tom Roberts (1890). Courtesy of National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The United States doesn’t eat much sheep. In 2020, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, Americans consumed less than one pound of lamb or mutton (the meat from mature ram or ewe) per capita. Americans are among the world’s top consumers of beef, pork, and poultry—and near the bottom when it comes to sheep. Why do Americans prefer other meats to lamb? And why, in a famously dynamic country, has this preference lasted for hundreds of years? Lamb’s unpopularity has deep roots in the history of sheep, and the outsized role that small animal has played in American agriculture and culture.

The Spanish conquistadors brought the first sheep to North America in the 16th century, when they arrived in present-day New Mexico. Later in the early 17th century, English, Dutch, and Swedish settlers brought sheep to the East Coast, and from there spread to other areas in North America. Initially, sheep met the settlers’ daily and immediate needs for wool to weave into fabric for cold-weather wear, as well as for meat. Sheep were eaten seasonally in the spring and summer on the farms where they were raised. Beyond that there was little or no market for mutton in the United States.

In the early 19th century, sheep farming developed into a larger industry because of an increased demand for wool in both national and international markets. By 1830 the growing wool manufacturing industry became increasingly important for the American economy, which demanded more domestic wool. This consequently resulted in increased meat output, as sheep were slaughtered at the end of their wool-productive life. At that time, the meat industry was locally concentrated where farmers sold these animals seasonally to nearby local butcher shops that supplied the local demand. For many more years, however, meat became a secondary product.

From the 1860s on, as the nation industrialized, urbanized, and grew wealthier amidst a wave of European immigration, demand for mutton rose. Midwestern meatpackers turned this meat into a buffer against periods of meat scarcity. When other meats ran short, meatpackers sent buyers to the western states—including California, Texas, and New Mexico—to secure castrated male sheep for slaughter.

Sheep meat markets developed in major cities such as Philadelphia, Boston, and New York. Sheep meat was more expensive than other meats and more appealing to the upper classes, so for much of the 19th century mutton or lamb was a rich person’s meal.

In the 1880s and 1890s, young lamb meat gained some popularity as a festive food with upper classes. A young lamb industry, known as a “hothouse,” developed in the East Coast and Midwest. These lambs reached the market by Christmas, and most of them were slaughtered by early spring. It was a prosperous business that remained seasonal.

Greater production reduced some costs and lowered prices, making sheep meat more affordable for low-income households. But beef and pork production also ramped up, and those meats became cheaper, too. Beef sold the best, and large meatpackers who had come to dominate the industry after the development of refrigerated railcars focused on that business.

Americans came to see mutton as an alternative meat, an inferior substitute in times of shortages and disruptions in the beef cattle and pork industries—you ate sheep only when there was nothing else. In popular culture and media, sheep meat was described as unpalatable animal waste. In 1897, a Ranche and Range article stated, “many people settled down to the belief that mutton was poor food.”

Sheep also came to be seen as a meat for immigrants, particularly those from southern and eastern Europe, who were America’s most reliable lamb eaters. American Indian tribes, particularly in Navajo country, also embraced lamb. These social and ethnic associations with sheep meat cemented its outsider status. Meanwhile, the meatpacking industry promoted beef as quintessentially American.

Not all bias against sheep meat was grounded in social prejudice. Some American consumers lost confidence in sheep meat after reports of meatpackers marketing lower-grade mutton and old ewes. Early in the 20th century it also became known that some retail butcher shops sold goat meat as lamb and mutton. Several sheep disease outbreaks made national news during the 1890s and early 1900s, deepening fears about the safety of eating sheep meat.

Americans soon lost not just their taste for sheep meat, but their talent for producing and preparing it. Local butchers did not dress (or gut) the sheep carcasses properly, or use proper mutton-cutting techniques. They did not always remove the red membrane that lines the inner surface of the lamb before cooking it. The waxy, lanolin flavor of this skin—the so-called “caul” or “fell”—may well have been why sheep acquired a reputation for being gamy and having a disagreeable taste.

Prejudice against sheep meat grew so great that it became too hard to change most Americans’ minds. World War I didn’t help. A 1917 “eat-no-lamb” campaign discouraged eating sheep that were needed to make wool. Then, with meat running low, Americans temporarily turned to eating sheep, and they remembered why they hadn’t liked it. Older, mature sheep being slaughtered during the war had a strong flavor and a tough texture.

After the Great War, mutton consumption remained low despite big price drops. Sheep raising became unprofitable for many operators in the West due to both excess supply and very weak demand. By then, the average per capita consumption of sheep meat in the United States was only five pounds per year, versus 67 pounds of beef or 71 pounds of pork.

Woolgrowers, meatpackers, and wholesalers didn’t give up. They started developing campaigns to encourage lamb and mutton consumption. In 1919, the National Woolgrowers Association launched a nationwide campaign to boost sheep meat consumption in the United States (which still persists in some ways) with the slogan “EAT MORE LAMB.” The U.S. Food and Drug Administration attempted to help encourage the consumption of lamb and mutton as a means of conserving the available supply of pork and beef.

But 100 years later, none of these efforts have stuck. Since then, throughout the 20th century and into the present, production of sheep meat showed a significant decrease. Such decrease in production has been accompanied by higher prices of this meat responsible for the greater production costs. Overall profitability has been decreasing gradually due to higher production costs. Both high prices and short supply have diminished its consumption and prevented its increase. But also, there is a social sense of rejection toward sheep meat.

Today, sheep consumption tends to be seasonal—with lamb (and occasionally mutton) on American tables during Easter, Christmas, and other significant religious holidays. As the holiday season begins, sheep may be part of your celebrations—perhaps with a roast leg of lamb on your table but just as likely with a pair of wool socks in your pile of gifts.

Send A Letter To the Editors