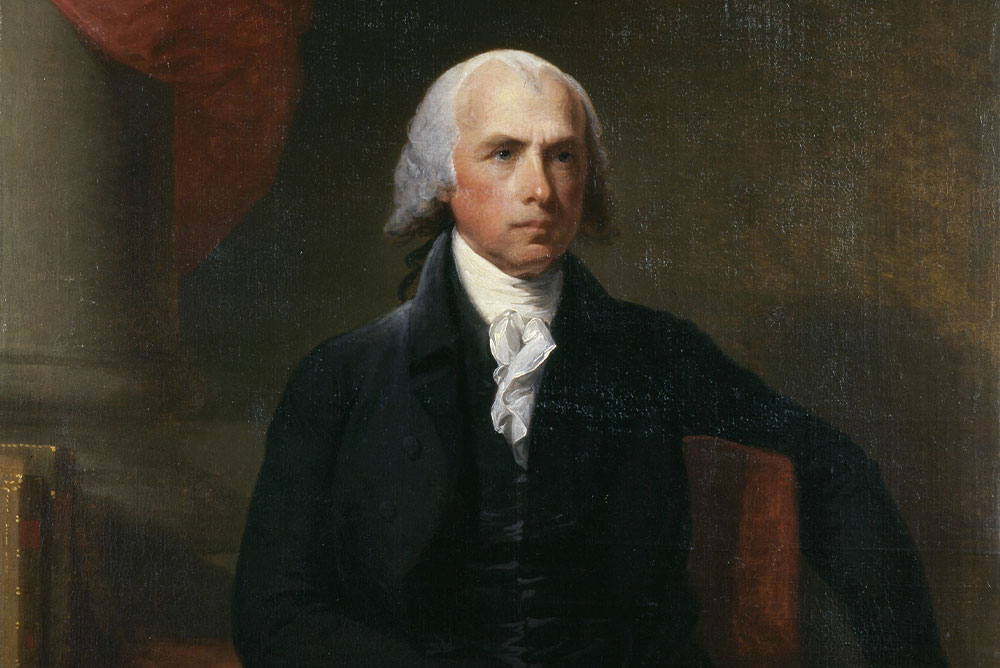

Portrait of James Madison by Gilbert Stuart, circa 1805-07, oil painting. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

One of the many law firms advertising in my part of Florida proclaims on a big billboard: “Size matters.” The crude innuendo is by now old and hackneyed. But America’s tiniest founding father, James Madison, co-author of the highest law in the land, would have agreed. Size matters a lot.

James Madison was 5 feet, 4 inches and slightly built. There’s little evidence to suggest that he was especially preoccupied with his own physical stature, but as “the father of the U.S. Constitution,” Madison was an intellectual giant who thought a great deal about size. In fact, Madison’s reflections on size can help explain why Americans today tend to be so disgusted with their political system but often seem at a total loss to know what to do about it.

Bear with me on this.

In 1787, Madison and his fellow Founding Fathers proposed to replace the Articles of Confederation with a new Constitution featuring a relatively powerful central government. Anti-federalist critics were aghast. They said it would never work because—as anyone who had studied history knew—republics had to be small, like Greek city-states. The republic proposed by Madison and his fellow federalists, stretching from New Hampshire to Georgia, would be enormous by comparison and was clearly destined to grow still larger. The anti-federalists dismissed Madison as a would-be power-centralizing aristocrat, and short too.

But Madison was thorough and persistent with his argument. The biggest problem faced by all republics was their tendency to split into narrow, self-serving, special interests, which Madison called “factions.” These self-serving interests can have a variety of natures. They can be political, religious, ideological, or commercial, the last being especially common. Such narrow selfish interests are normal in a free society, and can only be quashed through oppression—which in theory, at least, everyone’s against.

Madison turned on its head the conventional wisdom about the proper size of a republic. He argued that small republics easily became corrupt or tyrannical because it was relatively easy for one group or interest to form a majority, capture the government and oppress a minority. In a vast continental republic like the Unites States, however, there would be so many competing interests that none were likely to become powerful enough to take control of the government. Instead, those many interests would check each other.

Madison’s concept of interests checking and balancing each other, therefore, was not only applied to the various branches of government, as we are taught in school, but was considered a constitutional design feature that would be found within American society itself. Our large American republic, Madison concluded, had a good chance of being just, stable, and durable.

Madison was so enamored of his theory about the relative safety of a large republic that he obsessively argued it again and again, to anyone who would listen. The argument appears in Madison’s notes he kept while serving in the Continental Congress, in personal correspondence, in the records from the floor of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, and most famously, in “Federalist No. 10.”

Madison’s theory held up reasonably well for the first 60 years of the American republic, until an extremely powerful faction—the slave-labor-based economy of the Southern states—rose up in rebellion, resulting in the American Civil War, which is to this day both the nation’s bloodiest war and its most epic contest with a special interest.

After the Civil War, the power of the federal government began to grow. Progressives demanded government oversight to combat various social problems. The New Deal and Great Society expanded the government’s role in the economy and created large entitlement programs. The Cold War birthed the military industrial complex.

For good or ill, depending on one’s politics, today the federal government is many orders of magnitude larger and more powerful than the one imagined by Madison and his fellow founders. And that reality throws a big monkey wrench into Madison’s scheme for a government capable of resisting selfish interests. It is no longer necessary for a self-serving interest to gain majority support to corrupt the government, and thereby subvert the common good, because when government is immensely powerful it can serve innumerable selfish interests simultaneously.

Today, a voracious hoard of selfish corporate and political interests gorges itself at the trough of power at the public’s expense. The common and long-term well-being of the American people is an afterthought, at best. The public understands this quite well. When asked in an NBC/Wall Street Journal Survey, over 80 percent of respondents agreed with the following unattributed statement:

A small group in the nation’s capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the cost.

The quote, by the way, is from Donald Trump’s inaugural address. Would 80 percent still agree if they knew it was Trump who said it?

Probably not. Which points to another problem associated with size. In our time, it’s not only government that has become corrupted by interests. Large institutions that produce the knowledge, information, and ideas that a republic depends upon are also compromised. Media, which once at least went through the motions of taking journalistic standards seriously, now nakedly behave like other corporations; non-stop sensationalism and partisan narratives drive a views-and-clicks business model that sows division, and even hatred, among citizens. Tidal waves of corporate and politically-driven government money have corrupted universities, funding narrowly confined agendas. Independent scientific research is increasingly rare, particularly when it is costly.

The United States’ free market economy has always been a paradise for loosely bridled interests to run wild. Economically, the formula for channeling selfishness has been wonderfully productive. But when corporate interests capture the government, the free market is no longer free or safe for consumers. When politicians collude with corporate and other professional interests to form an entrenched political class, then the government no longer represents the people.

This should terrify everyone who is not part of the system and shame anyone with a conscience who is.

Our diminutive “Father of the Constitution” James Madison would have something big to say about all of this. In fact, he did say it. Again, Madison feared what selfish interests could do to his beloved American republic. He reasoned that in a large republic interests would check each other, and none become powerful enough to capture the government. It was a point that he reiterated so much that he must have been a bore at parties.

But Madison once revealed a dark fear he never expressed in public, because it would have undermined his signature argument about the relative safety of a large republic. To his friend, Thomas Jefferson, Madison wrote:

As in too small a sphere oppressive combinations may too easily be formed against the weaker party, so in too an extensive one, a defensive concert [author’s emphasis] may be rendered too difficult against the oppression of those trusted with administration.

By “defensive concert,” Madison is not referring to oboes and violins. What he means is that in a large and diverse society, people are easily splintered into squabbling factions when, instead, unity is needed to resist corruption, or worse. Madison’s prescience is astounding since this is exactly where “we the people” find ourselves today—in need of concerted action against public institutions captured by special interests.

Would-be citizen leaders need to step back and see what is really happening.

Ralph Nader, the famous consumer advocate, channeled his inner Madison when in 2014 he said, “It was quite clear to me many years ago, that power structures believe in dividing and ruling by distracting attention from areas where different groups agree to where they disagree.” At the time, Nader was promoting a new book, Unstoppable: The Emerging Left–Right Alliance to Dismantle the Corporate State. The subtitle was sadly premature.

Today, whenever an isolated leader stands up to truly challenge the system, he or she is likely to be demonized and demonetized. Platforms are withdrawn, public personalities smeared, reputations attacked, voices censored, private lives harassed, and employment terminated. For real leaders whose only desire is to serve the public, the public square has become an increasingly dangerous and authoritarian place.

We need, in Madison’s words, “a defensive concert.”

The first step to ending this endemic corruption and rising authoritarianism should be obvious: unified opposition balanced by authentic leaders on the left and right. Real leaders need to find each other in our large and cacophonous nation. Currently, dissenting voices are hunkered down in their silos, building their own brands when they should be uniting to build a movement together. Each voice alone is too puny to make a real difference but uniting and organizing could change everything. And it must.

Madison would argue that such a movement should have a clear overarching mission: to remove from the political system every incentive that favors service to selfish interests, or factions, over the common and long-term good of the American people. For starters, that means terminating political careerism and making it impossible for elected officials to take money, or otherwise benefit, from the various corporate and other selfish interests they are supposed to regulate.

It’s an enormous and complicated task, but it must begin somewhere. The people are ready. It’s leadership we need for the concerted action that James Madison, the tiny founder with his big ideas, begs us to take.

Send A Letter To the Editors