Zócalo illustration; images courtesy of British Library and Flickr/Tradlands (CC by 2.0).

When I arrived at Stanford, I was immediately confronted with the clues of my inferiority.

The other students had straight white teeth, more than one week’s worth of clothing, and “pocket money.” All I had was a load of imposter syndrome (though the term had yet to be popularized in the early ’70s), a suitcase of clothes, a box of books, a guitar, and stories; stories about the people I grew up with, and my large extended family in California and Mexico.

My stories about where I lived, or the race riots that marked my time in high school, police storming the students in the quad with batons and tear gas, were met with skepticism by my fellow students. Then, one day, a friend stopped me to say his class had just read Joan Didion’s essay “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” which describes a notorious murder trial that had taken place a few years earlier in San Bernardino County. It described the people of San Bernardino the way I did, he said, “but I never believed you.”

What is it about the printed word that makes a story credible? Why did Didion’s account change me from an unreliable source to a credible narrator?

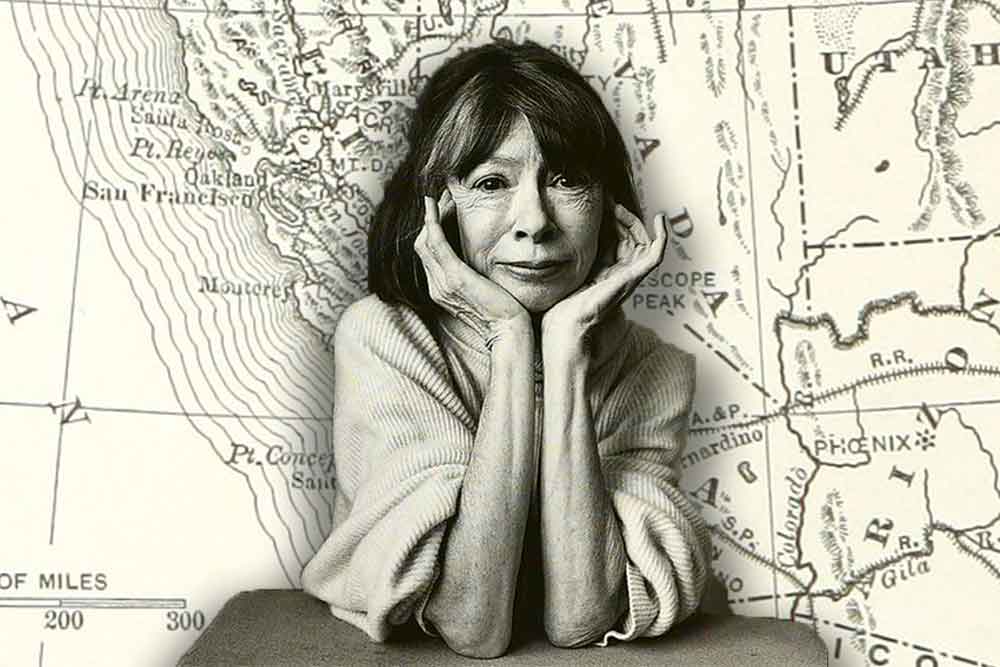

Since her death, I have been thinking about her impact on me as a writer. Before Didion, no one talked about the part of the world I grew up in. I thought journalism and storytelling took place in big cities, or Europe, or that Americans who got their books published were white men from the East Coast. But that day on campus, there it was: my childhood landscape as described by a woman, between the covers of a real book.

“This is a story about love and death in the golden land, and it begins with the country.”

From that first, declarative sentence in “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream” to its long, lingering description of a bride, the essay held me in its spell. Not necessarily the content, but the incantatory sentences that make the reader complicit in the web of truths and lies she is telling us. At the time, I was just learning about journalism as a cub reporter for the Stanford Daily. I remember taking a journalism class offered by the brilliant Bill Rivers, who took us through a series of exercises that emphasized the use of a few words that count.

It would be another four or five years until a friend at work brought me a well-worn copy of Didion’s essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, which included “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream.”

This was long before we had online access to information about people. Now I know that although from California, Didion was from an entirely different background than mine, the descendant of white settlers who declined to take the Donner Pass cutoff. Yet she was able to see the place much as I saw it, one where people, even white people, were striving to make good without much to start with, people seeking a way out, a shortcut to prosperity.

For my parents, immigrants from Mexico who had worked hard for their tenuous, lower middle-class position, this shortcut was to conform as much as possible to the prevailing post-World War II American culture, always somewhat foreign to them, even as its institutions were crumbling around them. My parents’ notion of a good life for me was one where I lived under their roof while attending the community college, and then worked as a teacher or nurse until I married a local boy, maybe one of my father’s former students at Franklin Junior High. I would have two children, at least one of them a boy to make up for the fact that I was the third daughter in our family.

This future had filled me with dread, and it pushed me to earn good grades, keep my scholarships, and keep hustling for jobs that would fill the gap between what I had and what I needed. The alternative meant to go home in defeat.

My parents did not understand my restlessness, my need for intellectual and physical stimulation. We drove two-and-a-half days to Mexico each summer to visit with my mother’s sister in Chihuahua, Mexico. Wasn’t that adventure enough?

But with Didion, I found a fellow traveler with a slightly jaundiced eye. For her, the strategy was to point out as many of the pitfalls of the American Dream as possible. Her work walks a fine line between compassion and scorn, and perhaps this is what drew me to her writing—the ability to be critical, yet care enough about detail to make readers understand this dual vision. Teatro Campesino, street theatre, and irony were beginning to seep into the wider culture, and my penchant for sarcasm and irony could find space in my work as a writer. While Didion could describe individuals with devastating accuracy, she maintained a certain distance to which I aspired.

It wasn’t our commonalities as women writers that interested me the most about her; rather it was her descriptions of the land. “Don’t you think people are formed by the landscape they grew up in?” Didion once asked. That first summer after my freshman year at college, my parents demanded that I return to San Bernardino for the summer. Upon arriving, I found that many of my former friends would not speak to me, afraid of being compared to the people in my new life. I applied for job after job in town, which resulted in work as a sales clerk for $1.20 an hour at the locally owned department store, The Harris Company, and a short-lived job with the Sun Telegram trying to pull ticker tape for regional and national stories quickly enough to suit the editors. Everyone in the newsroom except the ticker tape operator was male, including a classmate, the nephew of the editor-in-chief. There was no respite in town for someone who seemed not to belong in the first place. My friend who went off to Harvard came home and worked as a garbage collector that summer, which at least paid well.

But I still found solace there, in the mountains and wild places. For a few years, my parents owned a cabin in the San Bernardino Mountains located just above the smog line. I fantasized about owning it someday, but as with my sister’s ’68 Mustang, I was never offered the chance.

Looking at Didion’s work, and knowing now what I did not know then, that she was a world traveler more accustomed to airports than mountains, I am surprised at how well she understood the power of landscape. She treated it as a character, something I have tried to emulate in my own writing. By tying us to the land, stories give us substance and definition. Her stories brought the western landscape into focus, and while it was often treated as isolating and ominous, those images were a balm to a writer who grew up with that “hot dry Santa Ana wind that comes down through the passes at 100 miles an hour and whines through the Eucalyptus windbreaks and works on the nerves.” This was language I understood. And I understood that I could use it to make my way in the world. No matter what I write, the first draft often begins with a portrait of that land as a way of grounding myself before I set off into unfamiliar literary territory.

I met Didion once, before her life took a tragic turn, while she was in Seattle on book tour. She was as she described herself, slight verging on invisible. We had to strain to hear her speak from the stage. Like Didion, I am somewhat shy, so I’m sure I mumbled something about how much I admired her work, and she mumbled something back while we both avoided eye contact. It did not matter much exactly what we said. Whoever she was, Joan Didion gave me the courage to speak up, to bear witness, and to tell the story.

Send A Letter To the Editors