A subway in Kyiv, Ukraine, used as a bomb shelter. Courtesy of AP Images.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is not the first conflict to unfold on social media, but commentators have been quick to dub it the first “TikTok War.” Videos by young Ukrainians inside bomb shelters give us some of the most personal glimpses to date of teenage life inside a war zone. Amassing millions of views, offerings like “My Typical Day in a Bomb Shelter” and “What I Buy in a Supermarket During a War” document destroyed cities, bunker cooking, and daily life underground, with nuclear threat lurking offscreen. Broadcast on an unprecedented scale, these viral visuals of family shelters have worked their way into our collective consciousness, humanizing the headlines and bringing the threat of nuclear destruction directly to our devices.

But while the technology to share these images in Ukraine may be more advanced than ever before, the visuals of families in bomb shelters have always brought conflict to our doorsteps, making geopolitics concrete. A litany of photographs, government films, and Hollywood movies over the last 75 years communicates the public’s fears of nuclear war. These images offer us a nuclear temperature check of sorts, reflecting the shifting optimism, anxieties, and cynicism of the times.

It all started in Japan in the 1940s, in the immediate aftermath of the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when images of hibakusha (Japanese survivors of the bomb) and of cities reduced to rubble first emerged. Since then, Japanese popular culture has always kept the atomic bomb front and center, from genbaku bungaku (atomic bomb literature), to the recognition of Godzilla (1954) as an atomic text, to the global success of anime films such as Akira (1988) and the work of Studio Ghibli.

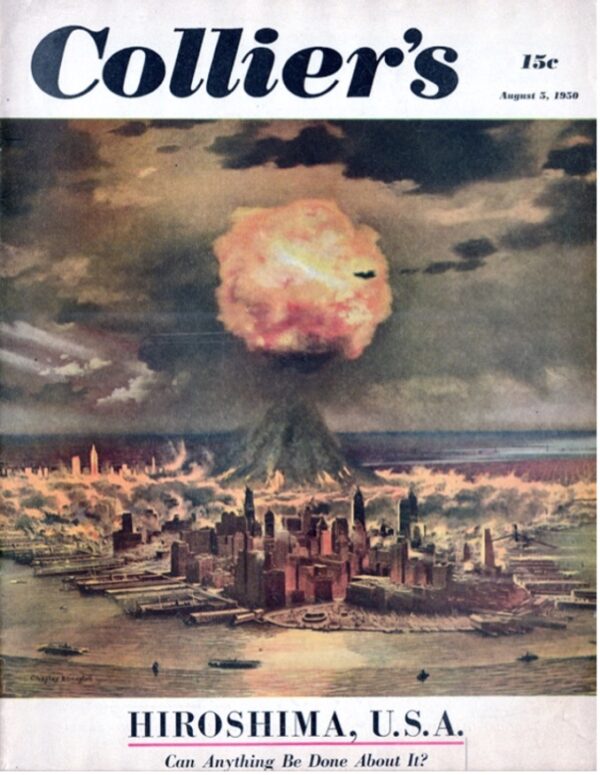

Hiroshima, U.S.A. Collier 1950. Courtesy of Smithsonian Magazine.

Each nation had its own unique cultural reaction to the bomb. In the U.S., the Federal Civil Defence Administration, founded in 1951, set out to convince Americans that if the bomb did drop, they could survive the fallout. Over the course of a decade, the agency attempted to quell public anxiety over nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union through public education campaigns, school room drills, and exercises.

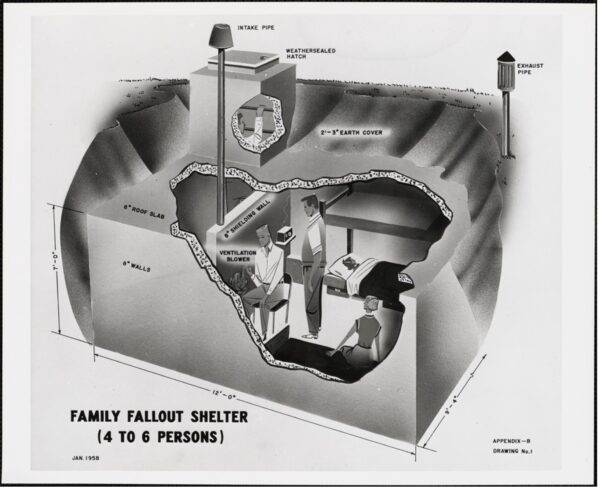

Nearly half a billion FCDA civil defence booklets depicted the All-American family in their fallout shelter—creating a key visual focal point for early conversation about nuclear war in the U.S. Decidedly suburban, heteronormative, and middle class in nature, this visual of white American families carefully lining shelter shelves with canned goods or taking their children by the hand as they walked toward their underground refuges broadcast a clear government-sanctioned message: A family that is together, well organized, and ready could survive the next war. Of course, the messaging had as much to do with domestic politics as with preparedness, reinforcing traditional ideas about marriage and family values.

Federal Civil Defense Administration Photograph Family Fallout Shelter. Courtesy of Digital Library of America.

Overlooking complex questions of class, race, and sexuality, this doctrine of DIY survival also shifted responsibility away from the state. Putting the onus on the individual might have been a cheap and attractive policy for the government, but the notion of a nation of shelter builders taking survival into their own hands could only go so far. With the development of the hydrogen bomb and the knowledge that nuclear fallout caused cancer and cardiovascular disease, by the 1960s the first generation to grow up in the shadow of the bomb began to question whether nuclear war was winnable in a traditional sense.

Women’s Activities and Conferences [1958-1960]. Courtesy of Digital Commonwealth.

The anti-nuclear movement grew out of this, and with it, pop culture images of the family fallout shelter took a turn for the cynical. In a 1961 episode of the Twilight Zone, a quiet dinner party turned into a community tearing itself apart as fictional suburbanites scrambled to get access to the only fallout shelter in town. In the run up to the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Saturday Review covered a town hall meeting in Hartford, Connecticut, which descended into chaos when a community member threatened to shoot anyone who approached his private shelter.

Depictions of fallout shelters continued to reflect the public’s shifting moods as the Cold War continued to fluctuate in temperature. When Vietnam dominated headlines in the late 1960s and 1970s, cultural discussion around family shelters largely disappeared; the shift from atmospheric to underground testing of nuclear weapons, the passage of the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, and a decade of easing U.S.-Soviet tensions also fostered an atmosphere of relative ease. But a generation later, the election of Ronald Reagan returned nuclear war to watercooler conversation. By 1984, politicians were obsessing over the “Evil Empire,” and pop group Frankie Goes to Hollywood topped the charts with “Two Tribes,” a single lamenting Cold War jockeying.

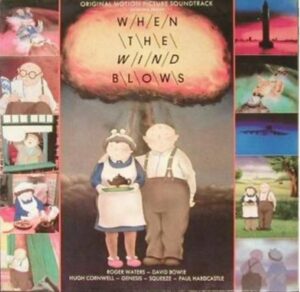

When the Wind Blows (1984). Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Fallout shelters re-emerged—though the family of the 1950s happily starting a new life underground had become a quaint relic of an already bygone past. In the 1980s, as global stockpiles of nuclear warheads totaled over 50,000, visual culture around shelters got increasingly bleak. With anti-nuclear activism heating up, the arts presented a society on fire, where the fallout shelter took on a new symbolic role: futile final bastion in a world devoid of hope. In the United Kingdom, where NATO stationed cruise missiles in 1979, filmmakers contributed two notable visions of bunkered families facing the end of the world. The animated feature When the Wind Blows (1986) told the story of an elderly couple, Jim and Hilda Bloggs, living in a tiny Cotswolds village after a nuclear strike rendered Britain a radioactive wasteland. The terrifying docudrama Threads (1984) dramatized the devastation of thermonuclear war in Sheffield and traumatized a generation.

The Cold War’s conclusion—the “end of history,” as Francis Fukuyama declared—repurposed shelters as historical relics, and in turn, they became objects of nuclear nostalgia in the culture. In the 1999 film Blast from the Past, for example, the family shelter became the perfect premise for a romantic comedy. Adam Webber (played by Brendan Fraser) is sealed away in his family’s bomb shelter during the Cuban Missile Crisis and emerges into the bustling modern world of the 1990s. Having grown up on a television diet of I Love Lucy and The Honeymooners, Webber’s efforts to find love render the fallout shelter a harmless time capsule of Cold War kitsch. Players of the first instalment of blockbuster video game Fallout (1997) took control of a “vault dweller,” similarly emerging from a bunker, to seek adventure.

Recent events have brought back images of family shelters, and today’s sobering shelter TikToks are whipsawing public consciousness again. It’s hard to predict what this latest paradigm shift will bring, with the situation in Ukraine being so fluid. What’s clear is that visuals of fallout shelters still shake us. Removed from carefully curated government pamphlets or movie sets, self-documented social media provides an uncensored and devastating look at the human costs of conflict through bunker life. The question is: will these new depictions of bunker life encourage this generation to create a world where nuclear fallout shelters can return to objects of harmless fiction once again?

Send A Letter To the Editors