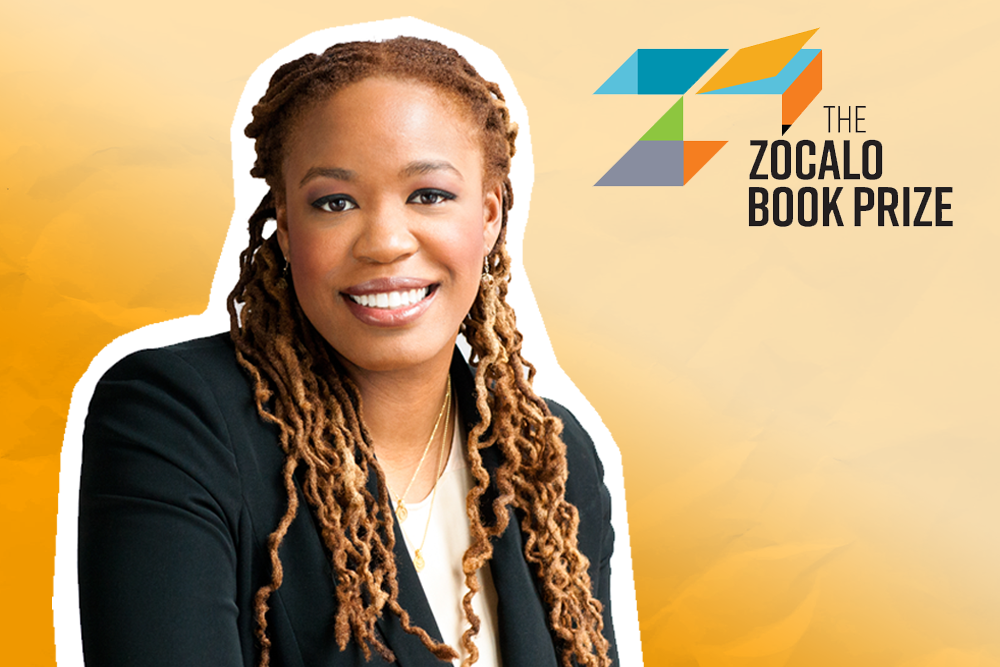

Picture courtesy of Penguin Random House.

Heather McGhee, the former president of the think tank Demos and a scholar of economic and social policy, is the winner of the 2022 Zócalo Public Square Book Prize for The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together.

Zócalo awards the $10,000 prize annually to the nonfiction book that most enhances our understanding of community and the forces that strengthen or undermine human connectedness and social cohesion. McGhee, our 12th annual winner, joins a distinguished group of authors that includes Danielle Allen, Michael Ignatieff, Sherry Turkle, and most recently, Jia Lynn Yang.

The Sum of Us opens with a simple question: “Why can’t we have nice things?” The answer, McGhee finds—when it comes to everything from public education and voting rights to environmental regulation and labor—is racism. For centuries, white Americans have opted to disinvest in public goods, services, and protections out of fear that people of color, and Black Americans in particular, would benefit disproportionately. The resulting policies have cost nearly everyone, leading to democratic dysfunction and deep economic inequality.

But McGhee found hope, too, as she traveled around the United States to research the book—in the form of stories of Americans coming together to fight inequality. The Zócalo Book Prize judges noted the book’s current of optimism in their praise. One judge lauded McGhee’s “call for all Americans to unite in ways that work toward eliminating racism so that we can all prosper together.”

The Sum of Us is “far-reaching in its accounting of what we all lose when public pools get drained, when racism pits workers against one another, and when the legacy of slavery fosters a political economy that spreads economic inequality and environmental injustice,” a judge noted. “McGhee shows us how to move away from the zero-sum thinking that has long antagonized race relations and toward policies by which we might refill our pools.”

The annual Zócalo Book Prize event, featuring a lecture and interview with McGhee, will take place on June 1, 2022 at 7 p.m. PDT. For the first time since 2019, the event will be held in-person in Los Angeles and stream live on Zócalo’s YouTube channel. The program will also honor Georgia poet laureate Chelsea Rathburn, winner of this year’s Zócalo Poetry Prize for “8 a.m., Ocean Drive.” Zócalo’s 2022 Book and Poetry Prizes are generously sponsored by Tim Disney.

We asked McGhee to talk about the themes of her book, the American stories that inspire her, and how she came to make the book’s central argument.

For most of your time at Demos and elsewhere, you were told that inequality wasn’t about race, or that it wasn’t wise to talk about race when the goal was changing public policy. How and when did you start pushing back against that narrative?

I spent nearly 20 years working in public policy, researching the hows—the mechanisms of rising inequality. How did we get to the place where 1 percent of the population owns more wealth than the entire middle class? How did we get to the place where nearly half of adult workers are paid too little to meet their basic needs? How are we still the only advanced, industrialized nation with no universal health care and family policy?

In those discussions, race would come up as a descriptor of disparity—as in, more and more families are working for poverty wages, and the problem is worse for brown and Black families; more and more families are struggling to afford childcare and college, and the problem is worse for brown and Black families. When I became president of Demos, I started asking deeper questions, which really got to the why. Why is our nation so singularly stingy with ourselves? Why are we such an outlier? Why does it seem like we can’t have nice things?

In the mid-20th century, communities around the United States chose to drain their public swimming pools rather than integrate them—including the state-of-the-art pool at Montgomery, Alabama’s Oak Park. In your book, draining the pool serves as both a metaphor and a potent example of America’s “zero-sum paradigm.” How did the pool come to play such a powerful role in the story?

Growing up, there was sort of a Black common wisdom of the experience of seeing public goods denied or destroyed in the wake of integration. However, when I first traveled to Montgomery and walked the grounds of Oak Park and asked where the pool was and saw the shrugs, and talked to people about the park’s glory days—it really hit home to me just how profound the loss was and how foolish and self-sabotaging it was for a city to destroy this jewel of its public infrastructure to avoid integration.

Can you explain what the “Solidarity Dividend” is?

Solidarity Dividends are gains that we can unlock only when we come together across race to address problems that no one can solve alone—things like cleaner air and higher wages and better funded schools.

Some of the most inspiring stories I came across during my travels researching the book were from communities long at odds with and distrustful of one another realizing that there were common solutions to their common problems. In Richmond, California, a multiracial coalition took on a big polluter, and in Lewiston, Maine, a multiracial coalition reinvigorated a dying small town and formed the backbone for a grassroots campaign to win Medicaid expansion in the state. In a multiracial democracy, it’s going to take people from all backgrounds to come together to solve the big challenges we face.

Have people and communities with similar stories approached you since the book was published?

One of the most recent trips I took was to Memphis, Tennessee, where a multiracial coalition in one of the most segregated communities in the country came together to successfully block the construction of an oil pipeline through southwest Memphis, a historically Black community. Memphis has one of the best natural sand aquifers and sources of water in the country, and this pipeline would have imperiled it. This wonderful coalition of white environmentalists and lawyers and activists and Black community members and homeowners came together in a coalition called Memphis Community Against the Pipeline. They were able to do something that rarely happens—they stopped the pipeline and were able to build a new sense of trust and movement-building in the city where the civil rights movement, as led by Dr. King, was cut short 50-something years ago.

The book explores racism and inequality through a number of lenses—from health care and labor to voting rights. Have you faced challenges regarding any subject in particular, where critics have suggested you’re overstating the importance of race?

I’ve been very fortunate in that the book’s been received with a lot of openness by people across the ideological spectrum. The one place where the argument seemed the most novel and there have been the most questions has been the link between racism and our unwillingness to address climate change.

We don’t have any distance from climate change right now. Everyone thinks of it as this present emergency, this present policy failure. It is often hard to see racism in these newer problems, as opposed to with issues like housing, where you can look at, “Oh, there was explicit racism in the past, so it makes sense that racism would have an impact today.” For climate change, we know who the figures are—we know ExxonMobil, we know the politicians who are not doing the right thing right now—and maybe there is a little resistance to naming the racism involving those very identifiable current actors.

The past is important to the book, which begins by going back to the origins of slavery in America. Was writing and researching history new for you, as an economist and legal scholar who has worked mainly in contemporary public policy?

The historical research was some of the most intellectually satisfying and fun. I got to be a student again. I learned a ton. It felt essential to explain how we got to this place, and to really hammer home the idea that for all of these aspects of inequality, it’s not a naturally occurring phenomenon. It’s about public policy choices, past and present. And what we see and how we live today is the result of decision making. I think that’s actually a very empowering message because it reminds us that better decisions can make for better outcomes. When the book first came out, it was an editors’ pick in the history category. And that was surprising to me—I’m not a historian, I did not set out to write a history book—but I felt like the prologue to our current situation was necessary in every chapter.

Send A Letter To the Editors