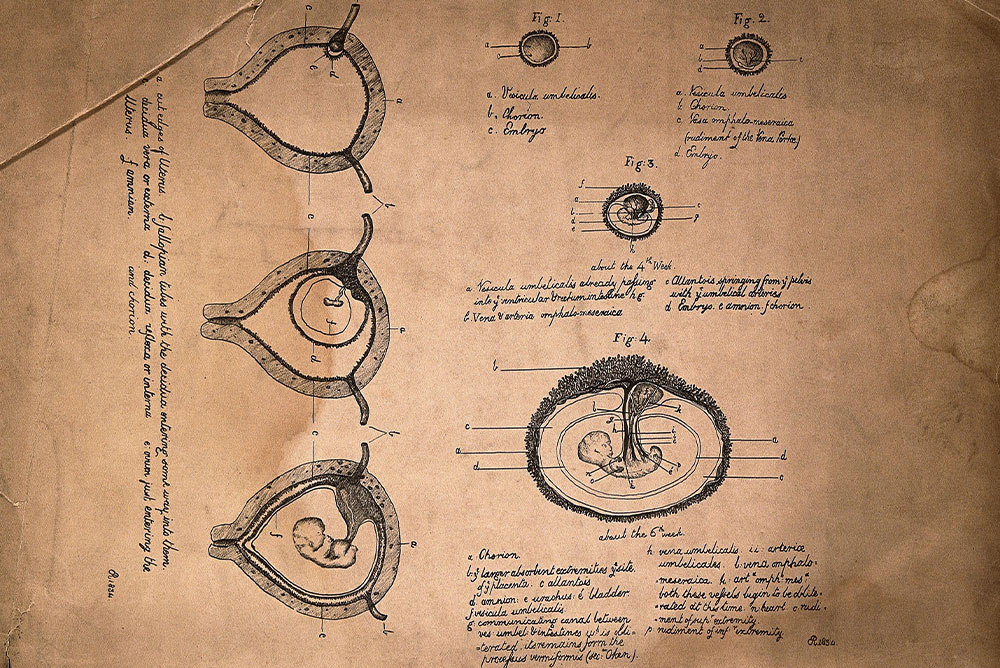

Lithograph of development of fetus in uterus, 1834. Courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

In the fall of 2012, I woke up early in the morning with cramps. I went to the bathroom and saw blood on my underwear. I was nine weeks pregnant, and it looked like I was having a miscarriage. I was surprised and sad, but also resigned. I had been researching and writing about the history of 19th century miscarriage for seven years, and I knew how often it is a routine part of a person’s reproductive journey.

I called my doctor’s office and was directed to the emergency room, where I sat for six hours, received two vaginal ultrasounds and three pelvic exams, and was repeatedly told I could not have any food, “just in case we need to do something.” I left with a $500 hospital bill, a headache, a noncommittal diagnosis of “threatened abortion,” and a new feeling of confusion and insecurity. Doctor after doctor told me, patronizingly, “We can’t find your pregnancy.” Despite what I thought I knew about pregnancy and miscarriage, that question made me wonder: Had I possibly read the pregnancy tests wrong?

Later, after things had run their course and I sat in bed with a heating pad over my abdomen, I could not help but think of all the women I had found in my research, women who miscarried at home, with family help, and who seemed free from recriminations, self-doubt, and self-blame. What had changed in the 150 years since then?

The answer is: reproductive expectations, limitations, and realities. Throughout history, people with uteruses have had miscarriages, and they have always understood the experiences within their personal family structures, within social and legal limitations on fertility control, and under the influence of all sorts of other factors, from trends in medical practice to racial politics. Today, those factors also include rapidly expanding legislation on the “rights” of the fetus taking priority over the health and life of the mother.

For women in the late 19th century, the factors and limitations influencing their understanding of miscarriage included a national ban on contraception and abortion. In January 1874, 26-year-old Annie Van Ness wrote in her diary: “I have been very cross and irritable and I think I have a very good reason to feel ill humored.” Two weeks later, she reported feeling much better: “Quite a change has come over the spirit of my dream since I last wrote, and I am happy again.” The reason for the change? Van Ness had a miscarriage.

When I first came across Van Ness’s words, I was surprised and fascinated. At a time when most white American women were besieged with messages that their duty and natural destiny was to have children, this woman was openly writing about how happy she was to fail in that duty. And she was far from alone. In 1879, Mary Cheney, a mother of nine who had spent 16 years in near constant reproduction—pregnant, birthing, or nursing—wrote her husband, after miscarrying: “O Bliss, O Rapture unforeseen! The imaginary number 10, whom I had already begun to love, is not a real entity as yet, and I hope will not be for a long time to come.”

According to today’s social narratives, miscarriage is almost always a loss, an event to grieve, and usually a secret. But in a world where women had much less control over their fertility, things were different. When Annie Van Ness got married in 1873, her husband had just lost most of his wealth in the recent economic panic. She had no interest in starting her family amidst financial instability, but she also had no reliable means to prevent or terminate pregnancy (both were illegal in New York, where she lived). Within such restrictions it makes sense that she was cross when she suspected she was pregnant, and happy when she miscarried. My first miscarriage, and the disappointment I felt around it, took place under very different circumstances: I had the ability to prevent pregnancy until I felt I had the financial and social stability to start a family.

Van Ness, Cheney, and I—and American women everywhere, for the last 150 years—have also interpreted our miscarriages in ways that are contingent on race. Throughout the 1800s, white male physicians were trying to gain a foothold in the business of delivering babies. Previously, most American women had given birth at home, attended by female family members, friends, and midwives.

To argue that they were the better attendants for birthing women, male physicians perpetuated a narrative of racial and ethnic difference in childbirth. They claimed that groups that were “closer to nature” or “more animalistic” (namely, African Americans and Native Americans) did not need medical help in childbirth because they were naturally better at the job. But white, “civilized” women were removed from ancient natural knowledge and couldn’t possibly take care of matters on their own. (White physicians, angling to practice new skills or experiment with procedures, also sought to deliver the babies of enslaved Black women but in keeping with the narrative, rarely offered them pain relief or comfort.)

Doctors all over the country promoted and presented “proof” for the “civilized versus savage” narrative. St. Louis physician George Engelmann, writing in 1881 in the prestigious American Journal of Obstetrics, contended that most “primitive” women’s labor “may be characterized as short and easy, accompanied by few accidents and followed by little or no prostration.” He added, “the nearer the civilization is approached, the more trying does the ordeal of childbirth become.”

This thinking, too, impacted women’s experiences of pregnancy loss. In 1846, Susan Shelby Magoffin, newly married and 18 years old, set off from Missouri on a trip down the Santa Fe trail with her husband. Six weeks in, she had a miscarriage. She spent the following week in bed, supervised by a physician. Reflecting on her sadness over losing her chance to be “a happy mother,” in her diary, she also noted that while she was suffering through the miscarriage, “an Indian woman gave birth to a fine healthy baby, about the same time, and in half an hour after she went to the River and bathed herself and it.”

Magoffin’s diary reveals both an intertwining feeling of failure and the ideas of racial disparities—and an acute difference in postpartum care. The perceived weakness of white women like Magoffin has resulted in their receiving increased care, resources, and protection. Meanwhile, women of color faced the next century of being denied medical and economic support for birthing and rearing their children.

The legacy of “savage” and “civilized” women popularized in the 19th century remains with us today, visible in well-documented health disparities. Black women face a maternal mortality rate almost three times as high as white women, and Black infants die two to three times more often than white infants. New laws criminalizing abortion, intrauterine devices (IUDs), and Plan B will make the gaps in care and resources between these groups more dangerous, and will affect a new generation’s experience of pregnancy loss anew. These laws will undoubtedly increase the surveillance and policing—and deaths—of members of those groups constructed as “naturally” good at pregnancy and childbirth.

Already, my own experience with miscarriage stands in stark contrast to those of women of color like Lizelle Herrera in Texas and Brittney Poolaw in Oklahoma, whose arrivals at the hospital were met with suspicion and even jail time.

I have felt myriad emotions for each of my three pregnancies that did not result in a live child, but as states continue to pass laws codifying fetal personhood and categorizing failed pregnancies as murder, such emotions will come under new scrutiny and suspicion. For women of color, reacting to a miscarriage in a way deemed inappropriate by medical practitioners or even neighbors will carry a much bigger danger.

Send A Letter To the Editors