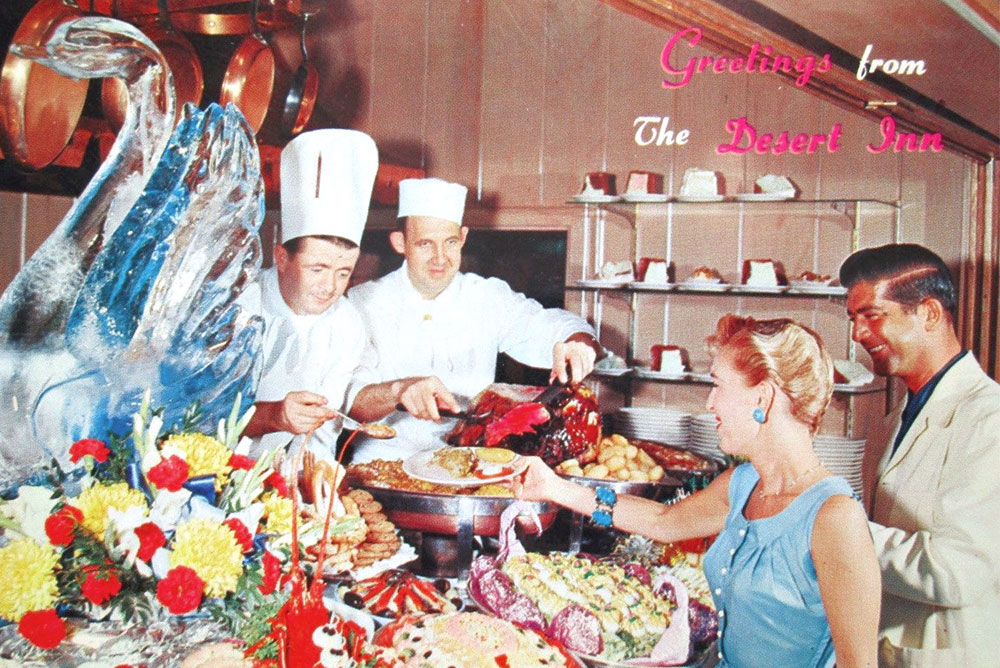

A 1953 postcard depicts the buffet at Wilbur Clark’s Desert Inn in Las Vegas, Nevada. Public Domain. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Growing up, few things loomed quite as large as a trip to the buffet. I say the buffet because the chafing dishes all blur together—part and parcel of one great, endless table; a physical manifestation of the infinite scroll before the infinite scroll had even been invented. To call it a meal would feel disingenuous; nothing short of “trip” captured the feeling of the experience, which stretched time and space and stomachs.

I’ve been thinking about buffets lately because, if you haven’t heard, they are back. The pandemic is far from over, but the health restrictions that turned restaurants and grocery stores away from self-serve buffets and salad bars have been lifted. And rather than the death for buffets that so many predicted in 2020 and 2021, the all-you-can-eat model has returned—modified somewhat, revamped with social distancing measures, but present all the same.

What is it about the buffet that keeps us coming back for seconds (and thirds, and fourths)?

The modern American buffet owes a debt to the smorgasbord, Scandinavia’s bread-and-butter table. The spread, which emerged in the 16th century, has its roots in the more formal brännvinsbord tradition, a spirits table that was served at banquets. Scandinavian immigrants brought the “smorgy” tradition with them to the U.S. in the late 1800s (the term smorgasbord reportedly first appearing in American print in 1893), where it merged with other fledgling forms of the buffet here. Historian Jan Whitaker has mapped the concept’s early history, from the “supper clubs” of the colonial era to the “free lunches” of the 1800s—spreads of food put out by drinking taverns to boost sales of accompanying alcohol. These became “buffets or cafés,” where, for a nominal fee, businessmen could secure prepared food without hassle.

Temperance movement teetotalers tried to scuttle these early buffets, but the model re-emerged, adapting to the times. During the Great Depression, for instance, the all-you-can-eat format was used as a gimmick to get people back in restaurants. The hope was that by creating a set price for an unlimited quantity of inexpensive food, people would be more incentivized to dine out. Even etiquette maven Emily Post helped promote this style of dining, with a calculated 1933 endorsement of the newly invented buffet server, which housed boiling water in a dish’s base to ensure that food stayed hot.

But the buffet we know today wouldn’t be what it was without Las Vegas. As the story goes, El Rancho Vegas, the first casino resort on what would become the Vegas Strip, was trying to figure out how to keep visitors from leaving after the evening headliner finished their set. The answer was the Chuck Wagon (later renamed Buckaroo) buffet, which debuted in 1946 and charged $1 for “every possible variety of hot and cold entrées to appease the howling coyote in your innards.” It was a hit. Other casinos scrambled to match the midnight all-you-can-eat supper—and by the 1950s, the Vegas buffet concept wasn’t just for late-night patrons with the Dunes and the Last Frontier resorts introducing morning “hunt breakfasts,” which took the name of a brunch forerunner, often served with champagne, popular among the U.K. elite.

This rise in buffet culture ballooned beyond Vegas, in chains like Sizzler and among mom and pop Chinese restaurants (the first Chinese buffet dates at least as far back as an advert for Chang’s Restaurant posted in the 1949 Los Angeles Evening Citizen News). My dad, for one, swears by Shakey’s bunch of lunch buffet. He describes the wonderment he felt sitting down for the first time in the 1970s to unlimited quantities of pizza, garlic bread, chicken. To him, the appeal wasn’t just about the value—though the value, he emphasizes, was incredible—nor was it the quality (which was good!). It was about the freedom—almost anyone could afford to sit down in Shakey’s and eat like a king.

It was this sense of awe that he passed down to me as a kid in the ‘90s, just as buffet culture in the U.S. arguably hit its peak. Searching my memories of this moment (to date it, this is the time when the term “Super Buffet” hit the collective American vocabulary), they almost feel as if they’re pulled out of that scene in Mad Men where the Draper family picnics in the park and just leaves all of their containers behind them on the grass on the way out. Just as littering wasn’t recognized as a global problem before the 1970s, I never questioned at the time the post-Cold War exuberance and hyper-consumption that Peak Buffet exemplified. I just remember the thrill of going back for plate after plate of food. This was the cheap abundance the era seemingly promised.

But like so much of that decade, the price tag was there, even if I wasn’t willing to see it yet. The food waste the buffet engenders can be nothing short of shameful—one 2017 report found that just over half of food put out in hotel breakfast buffets is actually consumed. And then there are the health concerns (one food safety trade publication charmingly dubbed it the “all-you-can-eat illness”), which had curtailed the buffet’s ubiquity even before COVID hit.

But the buffet can evolve. Take the position of Food Unfolded, a European Union-funded platform for reconsidering the future of food. It proposes we can rethink the buffet coming out of COVID in a way that makes a path for them to serve sustainable and fairly produced food and minimize waste and germs.

The potential to recreate itself in better ways, after all, is in the buffet’s very DNA. Its earliest iteration, feasting, is a tradition that dates back centuries, in foodways around the world. Cultures have long used such all-you-can-eat affairs to promote feelings of fraternity, to repurpose leftovers, and even as a source of culinary innovation, as the need to differentiate dishes demands new ways of mixing ingredients.

I admit it: I miss the buffet. With COVID cases back on the rise, I won’t be returning to one anytime soon. But I look forward to the day I’ll be back to fill my plate once again. Because a truth about the buffet is that it keeps you wanting more.

It makes me think back to my family’s favorite buffet story, which takes place, fittingly, just a few miles off the Las Vegas Strip at Sam’s Town’s now-shuttered “Great Buffet.” As we were nearing the end of the night, a family friend opened her purse, placed a napkin over its contents, and scooped a serving of trifle—a dessert with thin layers of cake soaked in sherry or wine, fruit, and cream—straight inside. I remember the jiggle as it settled before she carefully closed the bag around it.

When she caught us, seasoned buffet veterans, staring, she looked at the purse, looked again at us, and said, “In case I get hungry later.”

Send A Letter To the Editors