Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Bentwood Box, made of western red cedar, by artist Luke Marston, member of the Stz’uminus (Chemainus) First Nation. Commissioned in 2009, the Bentwood Box traveled the country with the TRC, collecting items from Residential School survivors until reaching its home at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba. Traditional bentwood boxes were used for collecting and storing food and goods, such as medicine. Courtesy of United Church/Flickr.

Can democracy stand the test of time? Many factors have triggered the deep schism in American politics today. But a root cause of our faltering democracy may be our failure to grapple with the truth about the nation’s history of discrimination and institutionalized racism. Because Americans can’t even agree on basic truths about our history of exclusion, slavery, and Jim Crow segregation, we have become mired in contentious debates about what role, if any, the government should play in addressing past injustices and their present-day legacies. To forge a path ahead, Americans must acknowledge our problematic past and collectively commit to upholding the principle of liberty and justice for all.

Where could we possibly start? As a first step, we can look to other nations that were once deeply divided, and learn from their efforts to address their difficult histories in pursuit of accountability and justice. The United States might do well to consider transitional justice approaches—the political, social, and legal processes societies use to respond to legacies of systematic or serious human rights abuses, primarily during periods of political transition like changes in leadership after a period of civil war or conflict, or the transition from an authoritarian to a democratic political system. These temporary judicial and non-judicial mechanisms and practices include criminal trials and prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations, and institutional reforms to help transform a society and reestablish the social contract. The United States is not undergoing a political regime transition, but transitional justice tools can still help us promote national reconciliation and reinforce our democracy as we reckon with the truth of our history and legacies of systemic harm and oppression.

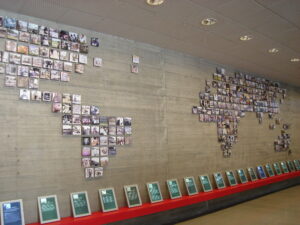

The “Human rights, universal challenge” room at the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago, Chile, showing a map of human rights abuses around the world. Courtesy of Warko/Wikimedia Commons.

The truth commission is a widely used transitional justice instrument—and one that can offer the most insight to Americans looking to reshape the collective memory and conscience of our nation. These official fact-finding bodies investigate, document, and disseminate accurate information about past wrongdoing and human rights violations authorized or carried out by the state. The United States can certainly learn a great deal from the successes and failures of these commissions in countries like Argentina, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Morocco, Peru, South Africa, South Korea, and Timor-Leste (East Timor).

The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) is one of the best-known national truth-telling and reconciliation processes and has been the model for several other truth commissions. In 1995, South Africa’s newly elected democratic, multicultural Government of National Unity established the TRC to investigate serious human rights violations perpetrated under the apartheid regime from 1960 to 1994. Apartheid was a brutal system of white minority rule and legally enforced racial segregation that formalized and expanded white supremacist and segregationist policies that had existed since the period of colonial rule. Institutionalized racism stripped Black South Africans and other non-whites of their civil and political rights—including their citizenship—and created extreme inequality and poverty. Anti-apartheid protests, demonstrations, and strikes organized by freedom fighters were met with swift and ruthless repression, and an estimated 21,000 people, the majority of whom were Black South Africans, were killed in the political violence during the apartheid era.

The primary purpose of the TRC was to promote reconciliation and forgiveness among all South Africans, while holding perpetrators of human rights abuses accountable for their actions. The commission’s work involved a systematic process of investigating human rights violations, organizing public proceedings where victims and perpetrators could testify, offering reparations to victims, and granting amnesty to perpetrators under specific, limited conditions. The TRC’s mandate covered both violations committed by the state and by anti-apartheid liberation movements. In its comprehensive final report, which the government endorsed, the truth commission outlined detailed recommendations for reforming the political system and civil sector, which included financial and symbolic reparations. President Nelson Mandela also apologized to victims on behalf of the state.

The TRC faced some criticism for its amnesty provision and the limited identification of perpetrators, among other things. Many South Africans later railed against the government for its delay in implementing the TRC’s recommendations, including the reparations program. But despite these critiques, the TRC succeeded in making sure the crimes of apartheid would be fully documented so that South Africa’s horrific history would never be forgotten. And in the decades since, the TRC’s broader emphasis on truth-telling, social transformation, and national reconciliation have made it a standard for other justice and accountability efforts around the world.

Inspired by truth and reconciliation processes in other countries and recognizing the need to educate Americans on the historical context for current racial inequalities, in early 2021, Rep. Barbara Lee (CA-13) and Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) called for the establishment of a national truth commission in the U.S., proposing legislation to create the United States Commission on Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation. The history Americans must reckon with is not as immediate as South Africa’s, and our political system is not in a moment of democratic transition. But similar efforts have succeeded in non-transitional societies, notably in Canada, which established a truth commission in 2008 to investigate, document, and educate Canadians about the abuses that occurred in the Indian residential school system for Indigenous children over the 19th and 20th centuries (between 1894 and 1947 attendance was made compulsory). These residential schools are a legacy of Canada’s colonial system and have been described as a form of “cultural genocide” because of their explicit goal of cultural erasure, and forcible assimilation of Indigenous peoples. The Canadian TRC documented widespread physical and sexual abuse in these schools, and officially recorded the deaths of 3,201 students, though concluded the actual toll is much higher. As part of its work, the commission hosted national events in different regions across Canada to support public education about the residential school system, pervasive discrimination, and the lasting trauma for survivors and Indigenous communities.

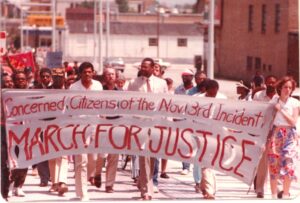

Citizens march for justice following the Greensboro Massacre of 1979. Twenty-five years later, community leadership organized the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Project to uncover the full harm done to victims of the domestic terrorist attack. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In the United States, there have been similar initiatives, organized by grassroots groups, to address abuses and wrongdoing at the local level. In 2013, the state of Maine’s Office of Child and Family Services with the support of the Wabanaki Tribes established the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission (MWTRC) to investigate and document state child welfare policies, their compliance with the Indian Child Welfare Act, and their effects on the Indigenous Wabanaki people. The commission collected testimony and found compelling evidence of public and institutional racism toward the Wabanaki people, documenting how Native children in Maine were placed in the foster care system at a rate of more than five times that of non-Native children, and concluding that the administration of child welfare by the state constituted a form of cultural genocide. The commission wanted to provide opportunities for truth-telling and healing, give voice to the Wabanaki people, establish a more complete account of the history of the Wabanaki people, and foster deeper understanding and reconciliation between Wabanaki people and the state of Maine.

The city of Greensboro in North Carolina also embarked on a notable truth and reconciliation effort, modeling the 2004 Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission after the South African TRC. Greensboro created its commission to investigate and document the underlying causes and consequences of a single event: the “Greensboro Massacre,” a confrontation between members of the Communist Workers Party, the American Nazi Party, and the Ku Klux Klan on November 3, 1979. During a “Death to the Klan” rally, Klansmen and neo-Nazis shot into the crowd, killing five demonstrators and wounding 10 others. Suspiciously, there was no police presence at the rally, even though the Greensboro Police Department knew about the planned attack. Despite eyewitness accounts and videotaped evidence, the Klansmen and neo-Nazis claimed self-defense and were acquitted of all charges by all-white juries in two separate criminal trials. During a civil trial in 1985, the Greensboro Police Department, the Klan, and Nazi Party members were found liable for one of the deaths.

After about two years of collecting evidence and holding public hearings, the commission concluded that the decision of the police to stay away from the rally was a significant factor in the violence that unfolded. The commission also found that the police department and city managers deliberately misled the public in order to absolve the police department of any responsibility. They found fault in the two criminal trials as well: Neither jury was representative of Greensboro residents and community members, which contributed to impunity for the killings, distrust of the police department, and further strained race relations. The Greensboro truth commission’s goals were multifaceted—to pursue the truth about racially motivated political violence; to foster healing, reconciliation, and social transformation; and to learn from other truth and reconciliation processes.

Send A Letter To the Editors