From left to right: Sandy Banks, Barbara Ferrer, Janette Robinson-Flint, Dr. John McHugh, and Allegra Hill.

As the full weight of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade bears down on the nation, California is seeking to become a sanctuary state for reproductive rights. The governor has signed a new law protecting Californians from civil liability for providing, aiding, or receiving abortion care. And the legislature is asking voters to pass a ballot measure to amend the California constitution to prohibit the state from interfering with their choices on abortion or contraception.

And such steps might just be a beginning.

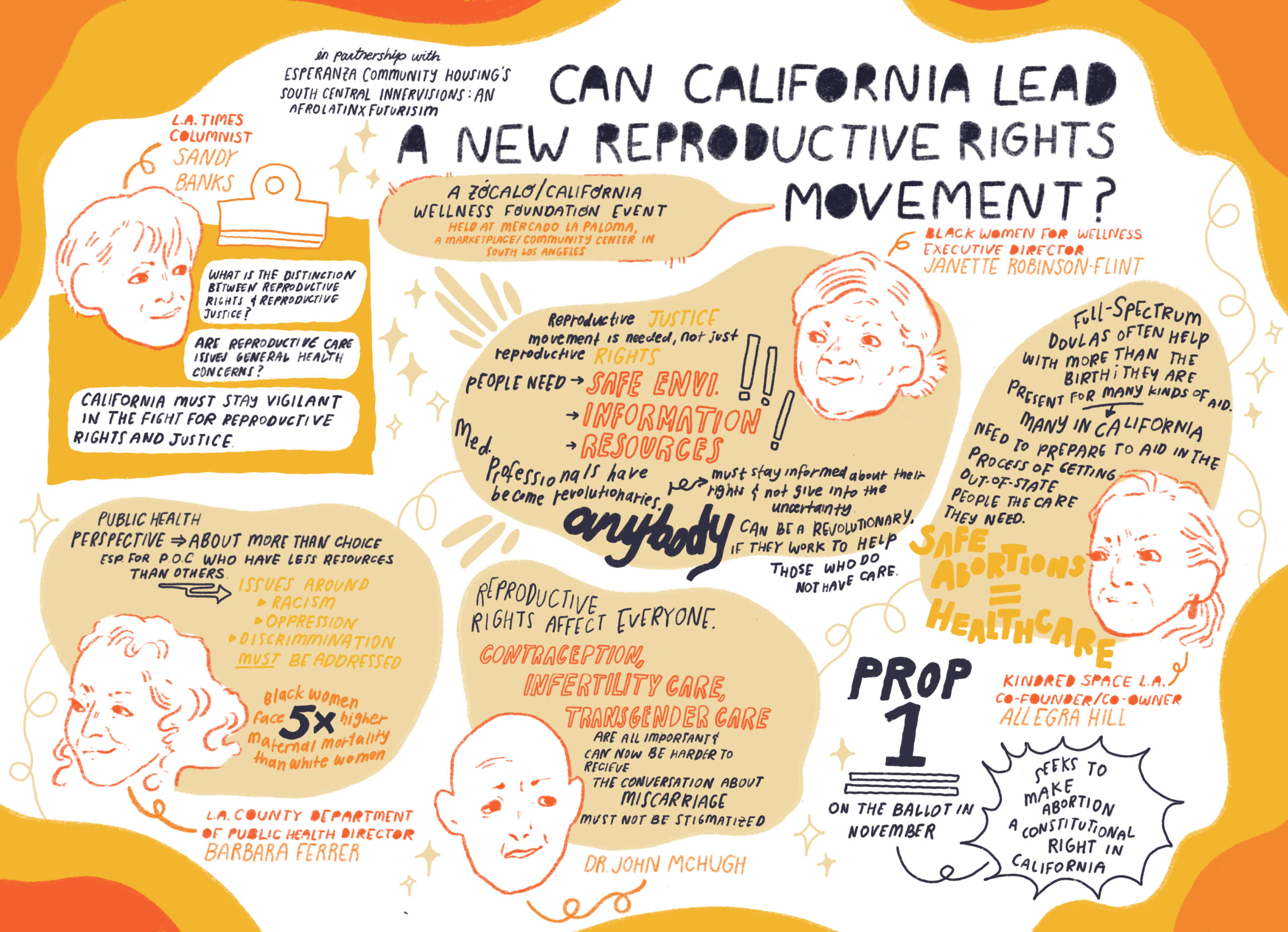

A Zócalo/California Wellness Foundation event, “Can California Lead a New Reproductive Rights Movement?” delved into the role of the state and its people in efforts to restore and extend the right to abortion, and other reproductive rights. The event—at the Mercado La Paloma, a marketplace and community center in South Los Angeles—was put on in partnership with Esperanza Community Housing’s free, multidisciplinary arts festival South Central Innervisions: An AfroLatinxFuturism, which starts Saturday.

Under a backdrop of artist Dominique Moody’s painting “When We Rise, Creating Our Next LA,” the panelists spoke about what it would truly mean for California to take a forward-looking role in healthcare access.

They argued that true leadership will require building a “reproductive justice” movement, which addresses not just the legal rights of women, but larger systemic problems of racism and oppression.

Panelist Janette Robinson-Flint, executive director of Black Women for Wellness, has spoken about the differences between reproductive rights, health, and justice, and Los Angeles Times’ Sandy Banks, the moderator, started the conversation off by asking her to explain these terms, and why it matters that we define them.

“The shortcut for reproductive justice is the right to have a child and raise a child or to not have children,” said Robinson-Flint. In building such a movement, she said, the state needs to look at the intersecting questions that influence and direct your decision-making around childbearing. Are you in a place you want to be in your life? Do you have housing? A job? A healthy environment? Your answers to all these questions, she said, impact the decision on whether or not to have a child.

Barbara Ferrer, director of L.A. County Department of Public Health, built on Robinson-Flint’s answer. In 2022, she pointed out, Black women have an almost five times higher rate of maternal mortality than white women, and Black babies are dying at a rate almost four times higher than white babies.

“That should be intolerable to all of us,” Ferrer said, which is why the fight for reproductive justice must be linked to the fight to dismantle racism and oppression. “You can’t separate the issues. I’ve been doing this work for a long, long time trying to address health inequities. The collective power we have is to do the work of a justice agenda and really talk about the root causes Janette laid out.”

Does that justice lens inform the state right now?

Banks said California seems most focused on securing additional funding and protecting residents or travelers to the state to access abortion.

“I think that’s up to us,” said Ferrer. “It’s really hard because we need both”—short-term actions and a long-term agenda that distributes resources fairly across the state. But she cautions “you need to be careful that your short-term agenda doesn’t wreck the real work that needs to get done.”

Banks turned to Dr. John McHugh, an obstetrician-gynecologist who is affiliated with California’s district of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “What are the things we’re not focusing on that we should be as we build this movement?”

McHugh answered that the attacks on reproductive justice are growing and finding new targets: “The politicians that want to tell you what to do with your healthcare provider aren’t going to stop at this. They want more than that. They want more control.”

Already, he said, legislatures in other states are going after contraception and transgender care. “This issue is not just about abortion,” McHugh continued. “It’s really about controlling people. About controlling a lot of aspects about peoples’ lives.”

“Is there a sense among obstetricians and gynecologists that this is a scary time or is there a militant sense?” asked Banks. “What would you say the practitioners are feeling right now?”

McHugh said people are feeling many different things. Some are taking action—he recently saw a proposal for a floating hospital in the Gulf of Mexico to provide care. But also, he sees the fear: “Physicians and not just physicians, nurses and health care organizations, some of them are afraid and cowering and pulling back.”

For example, he’s noticed that “some doctors are afraid to provide care for patients having miscarriages or even ectopic pregnancies because of uncertainty around this.”

Banks agreed. “I’m hearing stories now about women who have to almost die from ectopic pregnancy before it gets to the time that now you can intervene because now it has to do with saving the mother,” she said. “If there are women who are almost dying, there are going to be women that are dying.”

Robinson-Flint observed that in this post-Roe time, health care professionals have found themselves on the front lines of a revolution. Because providers have taken an oath, she said, to provide lifesaving services to their clients, they now have a decision to make: “Will they cooperate with this regime of terror that’s going on? Will they report their clients? Will they perform services? Will they report data?” Speaking to the crowd, she emphasized, “You don’t have to cooperate. You do not have to be responsive to vigilantes who want people’s data. And you don’t have to turn people away from care you can give.”

For more than 30 million people in Texas and Oklahoma, Banks noted, California might now be their nearest abortion provider. Directing her question at the final panelist of the evening, Allegra Hill, midwife and co-owner and co-founder of Kindred Space LA, Banks asked, “How, do we meet emotional, and physical, and after-care needs of these women? Because that’s part of reproductive justice too.”

Hill called attention to California’s “full-spectrum” doulas—people who are not medical professionals but who are trained to support people through miscarriage, birth, post-partum, and more.

“As this wave of people from out of state come here, we will have to adapt and pivot and make sure that our full-spectrum doulas are prepared to support people through traveling for a medical procedure, being separated from their own community, really meeting people here where they need the support,” said Hill.

The panelists also discussed funding for reproductive care, preventing maternal mortality (abortion access can save one-third of those lives, said McHugh), and the fall ballot measure to amend the state constitution.

Before the conversation wrapped, they responded to audience questions, as well, including one that asked if the panelists could each name a revolutionary in the healthcare field.

Banks mentioned the volunteers at Planned Parenthood. Robinson-Flint suggested that you can be a revolutionary by “exercising your autonomy”; she also cited doctors from Cuba providing healthcare around the world. Hill spoke about the “sister-friend,” somebody who can drive you to a doctor’s appointment, for instance.

And McHugh said anyone who talks about reproductive health issues is part of the reproductive justice movement.

“We need to talk more,” he said. “There’s so much shame and stigma about reproductive health issues.” But, if you feel comfortable testifying to your circle of people, McHugh said, it can “hopefully help someone else get the care they need as well.”

Send A Letter To the Editors