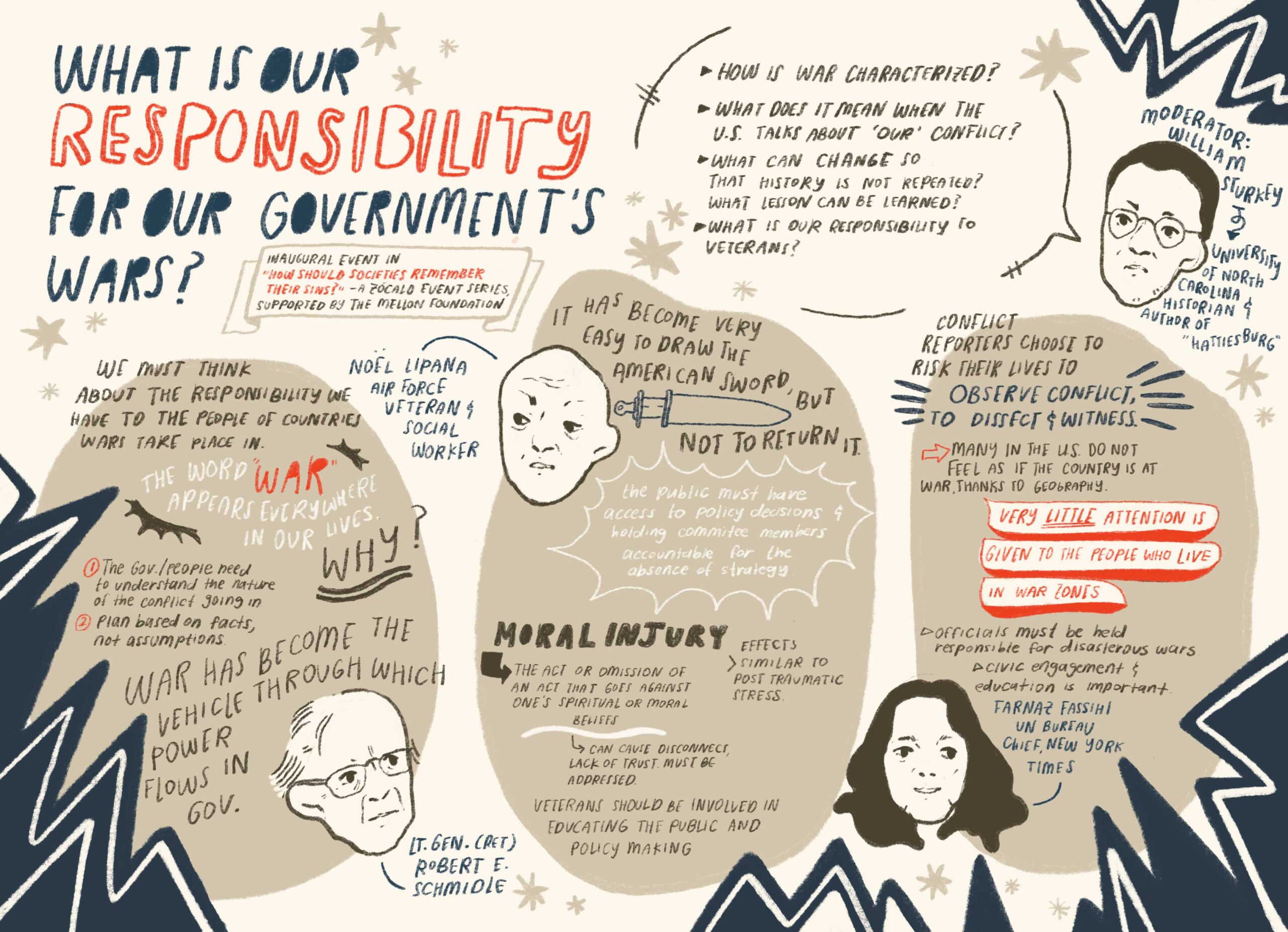

From left to right: Moderator historian William Sturkey, Lt. Gen. (ret.) Robert E. Schmidle Jr., Air Force veteran and social worker Noël Lipana, and New York Times U.N. bureau chief Farnaz Fassihi.

With wars playing a crucial role throughout history in shaping American influence and character—and with present-day conflicts devastating countries such as Ukraine and Yemen—Zócalo convened a panel to probe the question, “What is Our Responsibility for Our Government’s Wars?”

It was the first event of four in Zócalo’s events and editorial inquiry, “How Should Societies Remember Their Sins?,” supported by the Mellon Foundation.

The live, in-person panel at the ASU California Center in downtown L.A. featured Lt. Gen. (ret.) Robert E. Schmidle Jr. and Air Force veteran and social worker Noël Lipana; the final panelist, New York Times U.N. bureau chief Farnaz Fassihi, joined remotely via Zoom. All three drew upon their personal experiences in conflict zones to reflect on who holds responsibility for the devastating, ongoing effects of battle—those who fight wars, those who plan them, those who vote for them.

To launch the discussion, moderator William Sturkey, a historian at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and author of Hattiesburg, which won the 2020 Zócalo Book Prize, asked Schmidle to characterize war—and to clarify what it means when a nation like the U.S. talks about “our” conflicts.

Schmidle argued that all wars since World War II have been “wars of choice” for the United States. “War has become the defining way that this government and this country operates,” Schmidle said. We are either “at war or not at war,” and this binary determines how we conceptualize and attempt to solve all kinds of problems, at home and abroad.

At the same time that the U.S. engages in wars of choice, Americans don’t share the burden equally, Schmidle observed. He pointed out that the last war fought with the draft intact was the Vietnam War; from there, the U.S. moved to an all-volunteer force, which has drawn from a poorer, less-educated demographic and further insulated the more affluent from serving. By doing away with conscription, many Americans and their families are shielded from the realities of war. It is the “same reason we tend to build slaughterhouses away from populated areas. We try to civilize the things that we do,” he said.

The divisions between civilians and combatants were stark when, after 9/11, leaders deployed troops for the Afghanistan mission, while encouraging other Americans to go to the mall, spend money, and lead a normal life.

Fassihi echoed Schmidle’s sentiment, describing her time in Afghanistan and Iraq as a war correspondent. Thrice, when serving as the Baghdad bureau chief for The Wall Street Journal between 2003 and 2006, her offices were demolished. Even going to the market was “Russian roulette.” She compared this sense of danger with returning to JFK airport and feeling intensely that America had the “gift of geography […] where the general population doesn’t really feel like they’re at war.”

Lipana, who works with fellow veterans, agreed, and suggested that the distinction starts with the “implied social contract” when a volunteer takes an oath to support and defend the U.S. Constitution: “You make this immediate separation into becoming a combatant from civilian, non-combatant.” This positions veterans differently, granting them “the right to wage violence on the civilians’ behalf” and the responsibility of abiding by the laws of combat. But the promises of the contract are often not fulfilled: “You’re supposed to return to this place of peace and safety, and instead you’re launched into this second No Man’s Land.”

Lipana emphasized this point when he discussed moral injury, which he defined as an “act or omission of an act that goes against one’s personally held deeply spiritual or moral beliefs.” Moral injury plagues veterans, and often results in social isolation, unresolved guilt, shame, loss of identity and meaning. “I know how to die for my country. But how do I live for my country?”

Lipana also added that veterans want to believe all Americans are connected to the country’s democracy and decision-making processes—that “the machine works the way it should.” But that isn’t always the case, the panel agreed. The discussion turned to how people can hold their governments accountable—especially, Sturkey noted, during wars that grow unpopular like Vietnam and Iraq.

Speaking of her role as a journalist in conflict zones, Fassihi said she sees herself as a witness, navigating the agendas of actors on all sides to inform the public and policymakers. Traditional journalism has limits, she said: After she and her fellow correspondents reported on the disasters of the Iraq War, Americans reelected George W. Bush, anyway. Frustrated, she sent friends an email in the first-person that said, point blank, “this war is a disaster. Bush is lying.” It went viral. People wanted to connect with feelings on the ground—not just facts.

Schmidle agreed there was a need for accountability, citing government lies around 1968’s Tet Offensive during Vietnam and weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. He called out the U.S. government’s repeated practice of waging wars in places where it lacks basic understanding of the culture. Still, Schmidle, who serves as a faculty member at ASU’s Center on the Future of War, thinks emerging technologies like artificial intelligence could bring more oversight to warfare. He posed the question of whether it might be better to rely on A.I. and data than on humans to make decisions during war.

Prompted by an audience question about why America so often asks, “Why do they hate us?” Schmidle and Fassihi saw American exceptionalism as a myth that makes it hard for Americans to believe their country is capable of atrocious acts in war, or upending millions of lives over generations.

Our wars create large swaths of populations that see the U.S. as an invading force and an agent of economic insecurity, said Fassihi. “It’s very difficult,” she said, “to win hearts and minds when you’re holding a gun.”

Send A Letter To the Editors