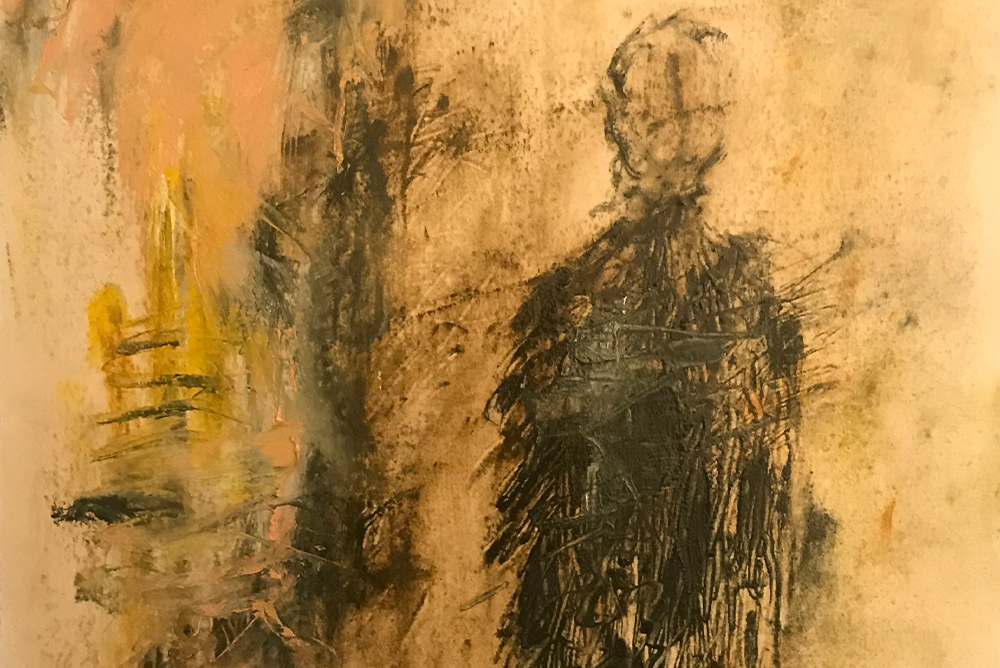

Through his research and work in collective trauma, Jack Saul has honed four practices for engaging responsibly with large-scale suffering. “Moral Injuries 4312,” oil on paper, 2018. Painting by author.

The subterranean strata of U.S. wrongdoing run deep—the genocide of Native Americans, the long history of slavery and racism, the effects of xenophobia, the illegal wars of aggression around the world. Today we are faced with the question: As a society, how will we remember and respond to these many past wrongs?

Approaches that take into consideration participants’ histories—along with their experiences of physical and mental trauma, and moral injury—seem to pay off.

For the past 25 years, I have worked as a researcher and practitioner in the field of large-scale psychosocial trauma. My current project, the Moral Injuries of War, seeks to probe the moral anguish experienced by military veterans and war correspondents deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq. It is an immersive audio installation, in which we overlay edited audio interviews and ambient sound. Veterans and journalists who are present at the installation provide comment after the 20- to 30-minute piece has ended.

By listening to their testimonies, the larger public can become more aware of the dilemmas faced by those at, and in, war. One goal of the project is to promote dialogue between witnesses of war and the rest of us, to help us work through our nation’s collective trauma—and hopefully begin to heal, as individuals and as a society.

Individual trauma may be understood as the consequences of experiencing an overwhelmingly stressful event or series of events. Collective trauma—what happens when society as a whole experiences shattering events—is, as sociologist Kai Erikson puts it, a “blow to the basic tissues of social life.” Collective trauma leads to a loss of a sense of belonging, decreased morale, social fragmentation, and conflict. Moral injury is an aspect of trauma people experience after participating in or witnessing actions which are morally reprehensible. It also manifests when we feel betrayed by persons acting in positions of authority. Moral injury has been described as a “wound to the soul.”

Addressing these devastating consequences of past societal wrongs is crucial—but it requires us first to determine how to prepare, emotionally and cognitively, for such an encounter. How do we stay grounded enough to integrate remembering into our lives in a meaningful way?

The answer is in what I call an “emotional toolbox,” stocked with four important practices that can help us heal. These include convening with care and purpose; listening with compassion; grounding, reflecting, and responding; and integrating a view or action and moving forward.

Convening with care and purpose

The most important thing is to create a supportive social environment with sustained respect. Who will remember with each other? Will it be just victims and their advocates; or conversation between victims and perpetrators, and their descendants?

A fruitful context for remembering has a clear aim. It helps to explicitly state the benefits. South Africa enacted the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to help rebuild after apartheid, and to bring about justice and accountability. In the U.S., the organization 400 Years of Inequality has worked to right the wrongs of slavery and the history of African American inequality while other endeavors aim to establish the truth about wrongs, as in investigations into forced adoptions and genocide of Native Americans. American remembering also seeks to prevent continued perpetration of wrongs in the future, as we are currently witnessing with the congressional investigation into the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Thoughtful convening includes processes for remembering and for forgetting; we may need to forget some aspects of the past to remain focused on what is important moving ahead. Collective remembering can be an organic process—one memory jolting another—a continuous linear narrative, or a patchwork of different perspectives. Whatever shape it takes, all in the community should have the opportunity to join in.

“Moral Injuries 3459,” oil on paper, 2018. Painting by author.

Listening with compassion

One must feel connected with a group to be ready to encounter heavy material. Clearly establishing intention builds trust. Creators or facilitators should explain why a difficult exploration is important for them. In the Moral Injuries of War project, we tell participants how we created the project: It came out of my clinical experiences working with war correspondents and veterans, who described their moral anguish to me during therapy. It became clear to me that witnesses and participants in conflicts could overcome their social isolation by breaking silences and sharing their stories with the public. Explaining this helps participants engage fully.

It is important to explain that participants may experience physical discomfort when they listen to witnesses. It is helpful to attend to that discomfort in their bodies, recognize where it is, take three deep breaths, and then return to listening with compassion to the person speaking. People should have the permission to stand up and walk around, or to leave the room for some time.

Grounding, reflecting, and responding

People confronted with disturbing material in the Moral Injuries of War project sometimes experience “shattered world assumptions,” where their previous views of the world, morality, history, and even their own identities may be disrupted.

To help mitigate this reaction, a useful exercise is to have each person engage with another person in the group to name their physical and emotional responses to the material. This helps ground the participants to one another, and enables them to respond to what they witnessed as a shared experience. Hearing a range of responses and perspectives within a bonded group helps participants engage in a conversation about what moved them or resonated with their own experiences, and what they have learned about themselves.

Once feeling grounded and having reflected on one’s personal response, witnesses and members of the public may thoughtfully engage in difficult conversation. The Vietnamese Buddhist monk and teacher Thích Nhất Hạnh knew the potential transformative power such a conversation can have. “Veterans,” he said, “are the light at the tip of the candle, illuminating the way for the whole nation. If veterans can achieve awareness, transformation, understanding, and peace, they can share with the rest of society the realities of war.”

“Moral Injuries 3354,” Oil on paper, 2018. Painting by author.

Integrating a view or action moving forward

As we go through deliberate processes of bearing witness to societies’ past wrongs, it is important that people walk away feeling resourced not depleted—touched not triggered. Remembering, done right, can instill a desire to make society better. One way to bring that about is to engage participants in small group discussions. What would they like to take with them from such an experience? What would they like to leave behind?

In the Moral Injuries of War project, we ask participants how they want to respond to the testimony they heard. Some have said they would like to find new ways to engage with veterans to learn more about their experiences. Some have told us they want to reach out to family members who fought in battle. Others were inspired to help refugees, especially of recent wars.

We follow talk with action, asking each person in our small groups to describe their intended response in one word or phrase, and then demonstrate that action in a gesture to the others.

For example, somebody who wanted to reach out to veterans described their action as “dialogue,” and then motioned their hands to indicate give and take. We play music and lead the group in dance. Each person shouts their word and expresses their gesture and the group reflects the words and gestures back. Participants leave feeling an element of hope, rather than being weighed down by the difficult material. Embodying the desirable action increases the likelihood that one will carry it out in the future.

Participants of the Moral Injuries of War project convene in Woodstock, New York. Courtesy of author.

The author James Baldwin once wrote, “It is the innocence which constitutes the crime” when perpetrators view themselves as innocent. A society cannot mature if it cannot move beyond its perceived innocence—especially when there are so many sins to remember.

Engaging responsibly with the suffering of others is an important step in the process, and is deeply humanizing. It develops our capacity for empathy, strengthens our connections to others and ourselves, and ultimately makes society better. My hope is that the emotional toolbox helps facilitate this.

Send A Letter To the Editors