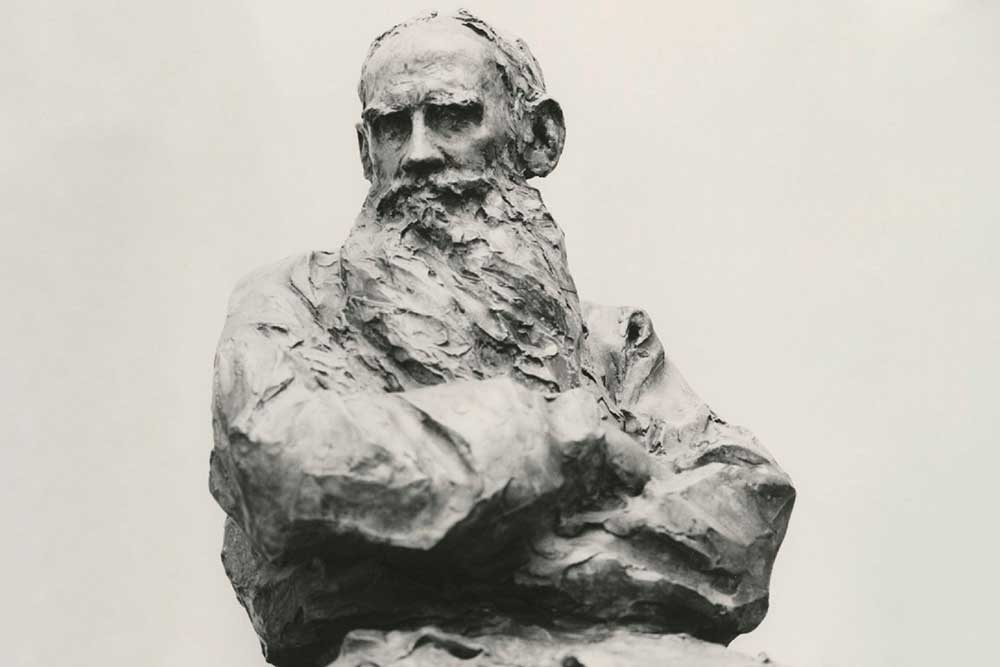

Pro- and anti-war groups are using Tolstoy and other great writers to stake out their positions, Jacob Lassin writes. Courtesy of David Finn Archive, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library.

On April 10, 2022, Moscow police arrested resident Konstantin Goldman for brandishing a book in public. Goldman had posted an image on social media in which he posed holding a copy of Tolstoy’s War and Peace next to a section of a World War II monument that commemorates Kyiv’s status as a Soviet “hero-city”—a distinction given to cities that endured some of the harshest moments of the Nazi invasion. He was charged with violating Russia’s prohibition against discrediting the military, a new law that can carry a punishment of up to 15 years in jail.

But Goldman’s photo went viral, tapping into latent sentiments against the lack of freedom of expression and repressive fear-based tactics. A meme began to circulate that modified the image so that the word “war” in the novel’s title was replaced with “special operation,” the term that the Russian government has been using for its invasion.

Literature has long occupied a key role in Russian culture. A popular adage describes poet Alexander Pushkin as “our everything.” The novels of Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky are lauded the world over as some of the greatest exemplars of realist literature. The famous Soviet-Russian poet Evgeny Evtushenko famously noted that “in Russia, a poet is more than a poet,” commenting on the central social role that writers have played.

Now, instead of bringing Russians together in pride for the country’s cultural achievements, literature is dividing them, being used both to advocate for the country’s war with Ukraine and to protest against it. Public intellectuals who support the war have marshaled Russia’s literary tradition as a symbol of the greatness of the Russkiy mir, or the unified “Russian world,” that the Putin regime claims to be defending in Ukraine; meanwhile, those who are protesting the war have used literature as a source of inspiration and material—even in the face of draconian new laws designed to silence opposition. Supporters of Russia’s military actions use references to Russian literature and culture to further a monolithic state narrative that discounts the uniqueness of Ukrainian identity while at the same time stoking fear that Ukrainian language and culture represent a threat to Russia.

Pro-war literary rhetorics began even before Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine. Last summer, Aleksandr Shchipkov, a political philosopher and deputy head of an international NGO concerned with the future of Russian society and questions concerning what constitutes “Russianness,” wrote on Russian social media platform Telegram that “Gogol and Shevchenko wrote in Russian and were actually Russian writers.” By folding Gogol, who was born and raised in Ukraine, and Shevchenko, Ukraine’s national poet, into the Russian canon, Shchipkov attempted to subsume the cultural achievements of which Ukrainians are proudest—even, in the case of Shevchenko, one of the foundational figures in the development of the modern Ukrainian language—into Russian culture. Echoing Putin’s insinuations that Russia and Ukraine are one nation, Shchipkov made literature into a tool for justifying the continuation of Russia’s colonial history in Ukraine.

Another trope seen across social media has used literature to reiterate the idea that the Ukrainian people are rejecting all of Russian culture. This is another of Putin’s frequent claims, based on little more than the Ukrainian government’s promotion of the Ukrainian language. In such framings, any perceived attempts by Ukrainians to demonstrate the unique elements of Ukrainian language and culture become an existential attack on the Russian nation. On April 8, the prominent author Zakhar Prilepin, who has fought on the side of pro-Russian Donbass separatists in eastern Ukraine, wrote on his Telegram channel that one “goal of a Ukrainian textbook of the Russian language” would be to remove all the Russian words from the Ukrainian language. (Because of Russia’s long domination over Ukraine, including the decades of the Soviet Union, many Russian words have come into the Ukrainian language; there is a movement by some Ukrainian activists to return to using more native Ukrainian words rather than use these loan words.)

According to Prilepin, the end result of re-substituting loan words for their original Ukrainian equivalents would be that “for the future ‘Ukrainian’”—putting the word in quotation marks to add even more aspersion on Ukrainian legitimacy—”Pushkin, Gogol, Dostoevsky and Sholokhov [the Nobel Prize-winning Soviet author of And Quiet Flows the Don] will become incomprehensible without translation into Ukrainian.” Invoking some of the most prominent names in all of Russian literature to stoke fear in his readers, Prilepin claims that those in power in Ukraine want to eliminate all traces of Russian culture.

Yet Russians have also used literature to make arguments against war—even when doing so carries a high degree of risk. Goldman isn’t the only one who has been arrested for invoking Tolstoy in a moment of protest. In late March, Russian police arrested Aleksei Nikitin, an activist from the southern Russian city of Krasnodar, for holding a sign with a quotation from Leo Tolstoy that, in English translates to, “patriotism is the renunciation of human dignity, reason, conscience, and the slavish subordination of oneself to those who are in power. Patriotism is slavery.”

To justify the arrest, the police engaged in their own effort at literary analysis. They issued a statement that read:

Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy is a historical figure who has been called, ‘the mirror of the revolution.’ It is a well-known fact that in his works and journalistic articles he heavily criticized the ruling regime, especially for its justifications for the use of violence during moments of social upheaval. Thus, the actions of Mr. A.N. Nikitin should be interpreted as following the ideology of L.N. Tolstoy and as a call to overthrow the current government as well.

In order to discredit a protester, the Russian authorities held Tolstoy—who despite his religious disagreements that led to his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church, remains one of the country’s most revered writers and one whose greatness has also been used to justify the war—as a direct threat to the state. Tolstoy, in other words, is too radical for Russia’s current regime. While the government might point to him as a great exemplar of Russian culture, anything beyond a surface-level engagement with his work is met with fear. The simple act of referencing his words and ideas have become proof of subversion and grounds for arrest.

The authorities’ fear is revealing. The Putin regime and its supporters are using Russia’s literary heritage to demonstrate the greatness and strength of the Russian nation, and to deny the very existence of a Ukrainian nation. When Russians who oppose the war look to that same literary tradition and draw upon it for their own positions, it shatters the illusion that there is a single, unified Russian literary tradition that supports Russia’s military actions. The Russian government cannot abide any dissent, even if it comes from literature. Yet part of what makes Russian literature so great is its complexity. The richness of the literature, combined with its profound cultural importance, assures that readers will continue to find counterexamples and new interpretations that challenge the state’s monolithic narrative.

Send A Letter To the Editors