Thirty years ago, General Motors employees crowded to sign the last car they’d ever assemble at the plant. The so-called “Last Camaro” became a “memento of what that plant had meant to them and their community,” write Andrew Warren and Tim Moore. Courtesy of Leonard Stevenson.

Improbably, the best monument to the old General Motors assembly plant in Van Nuys, California, sits in a garage in Jamestown, North Dakota—the final car produced at the facility that in its 44 years of operation manufactured 6.3 million automobiles and employed thousands in L.A.’s San Fernando Valley.

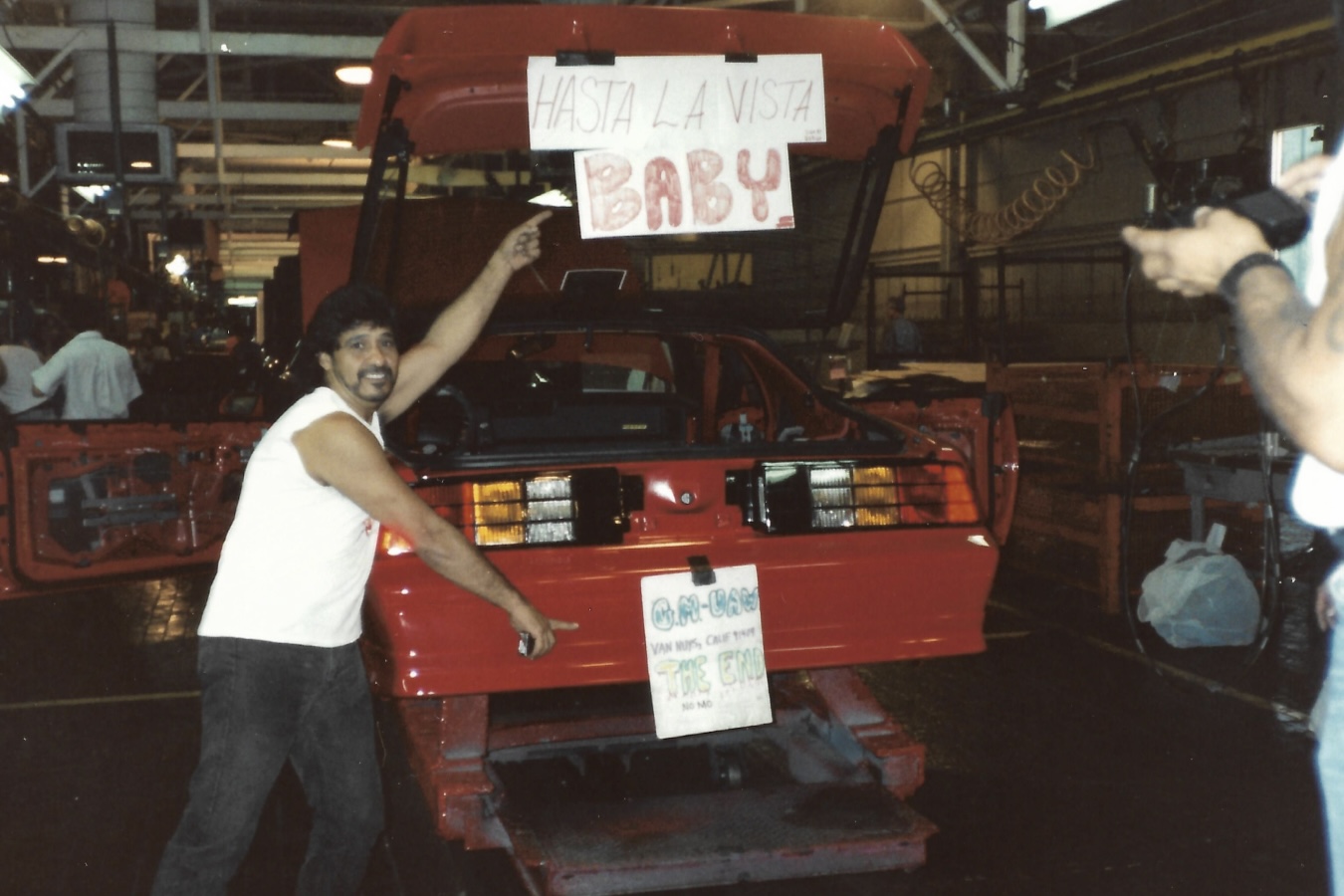

The red 1992 Chevrolet Camaro Z-28 with Heritage black racing stripes is owned by an enthusiast named Leonard Stevenson, who’s lovingly maintained it ever since he watched it roll off the production line on August 27, 1992. Three decades later, his “Last Camaro” is a symbol to a vanished era of labor and a tribute to a way of life in the mid-20th century San Fernando Valley—somewhat suburban and temperamentally apart from the rest of Los Angeles County—that has all but disappeared.

When the GM plant opened in 1947, the Valley was experiencing a period of rapid expansion—transforming from an agricultural outskirt of Los Angeles into a thrumming hub of industry to meet the ambitions of post-war America. High-paying union manufacturing and production jobs from GM and other companies, coupled with the cheap cost of land for housing and the opening of a major transportation artery—the Ventura Freeway—in 1960, put the peripheral L.A. suburb on the map.

The blue-collar boom went bust starting in the early ’80s. Los Angeles continued expanding and the cost of living rose. At the GM plant, there were years of layoffs and temporary closures, leading to picketing from workers of United Autoworkers Local 645. Finally, in 1989, GM announced plans to relocate Camaro and Firebird production to a new facility in Québec. Employees hoped the company would keep the Van Nuys plant operating; it still produced 406 cars per day, the equivalent of nearly one every minute. But by 1992, GM was no longer willing to bear the cost of assembling cars—any cars—in Southern California, and union power was on the wane, nationwide. Time had run out for UAW Local 645. Some 2,600 workers were employed at the Van Nuys plant when it shuttered.

Leonard Stevenson read the news of the plant closure in the trade magazines, sitting at his home some 1,700 miles away in Ankeny, Iowa. He’d already owned two vintage Camaros—a 1969 Z-28 and a 1991 model that he wrecked in a highway collision with a deer. He decided he’d buy the last car produced at Van Nuys as it rolled off the assembly line.

It was an outlandish idea, but Stevenson knew it was possible: In 1987, another GM customer had been allowed to walk the assembly line at the shuttering Pontiac, Michigan plant, and to purchase the last Buick Grand National. Stevenson launched a charm offensive, writing GM executives and asking, over a period of months, if he could have the Camaro. The car company eventually bit. Possibly its public relations team saw an opportunity, with Stevenson, to deflect attention from the closure and the thousands of layoffs.

At 5:30 a.m. on August 26, 1992, a plant executive greeted Stevenson in Van Nuys and marched him through the vast facility, following the assembly line until they reached the final car—the Z-28, its body already coated in a cherry-glossed red.

Unsurprisingly, the general mood at the plant that day was sour: the average length of service for Van Nuys Plant employees was 20 years and the average wage was $17 an hour—about $35 an hour in 2022 dollars. Now, it was all being ripped away. Some workers donned protest T-shirts—“GM Sucks,” “UAW Local 645– ‘Unemployed’ Auto Workers”—as they stood witness to the end of an era. “What is the American Dream now? Now they’re moving on and leaving everybody in the dust,” Ed Johnsen, a 16-year employee of the plant, told a reporter. He had met his wife, Patti, on the job.

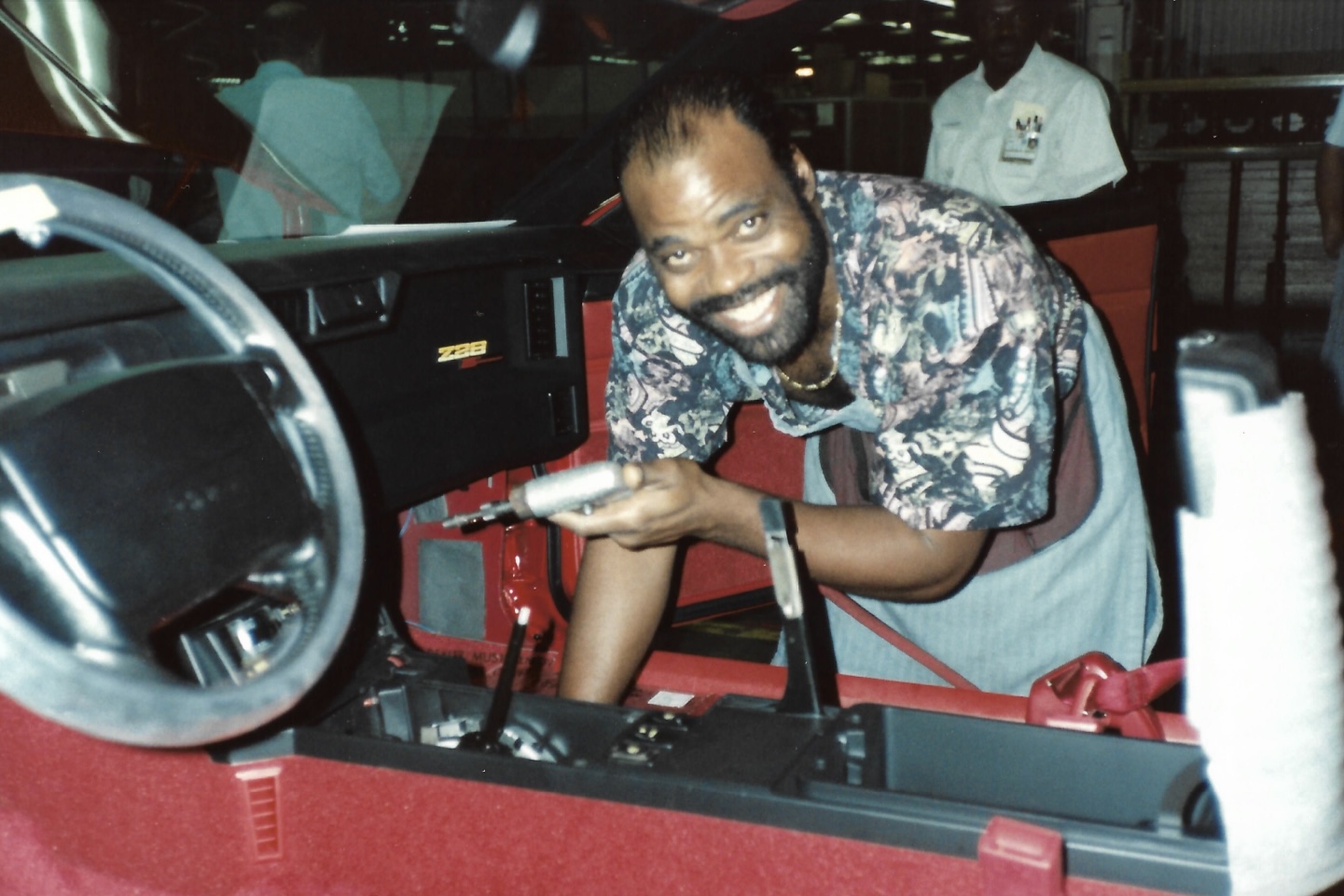

Stevenson’s visit offered the workers a small ray of light. The PR plan had been for him to walk the assembly line to watch the car get built, snap some photos, and head back to Iowa: a feel-good story about a car collector taking home a newly prized possession. But then something unexpected happened. Stevenson watched as first one worker on the assembly line, and then another, and then another, put their signature on the component they installed on the Camaro. They all wanted their names on the last car they’d ever build.

The executives asked Stevenson if he wanted them to stop. But Stevenson said he was fine with it as long as the signatures remained on the inside of the car, so they were not visible from the exterior.

And as the workers wrapped up, they also shared some of their knowledge with Stevenson. When it came time to install the car’s dashboard, technicians detailed precisely how they did it, showing Stevenson the computers that they used to confirm cars were built to specification. One worker even took off his Camaro belt buckle and handed it to Stevenson.

After the workers down the line signed the car, they turned in their badges and clocked out for the final time.

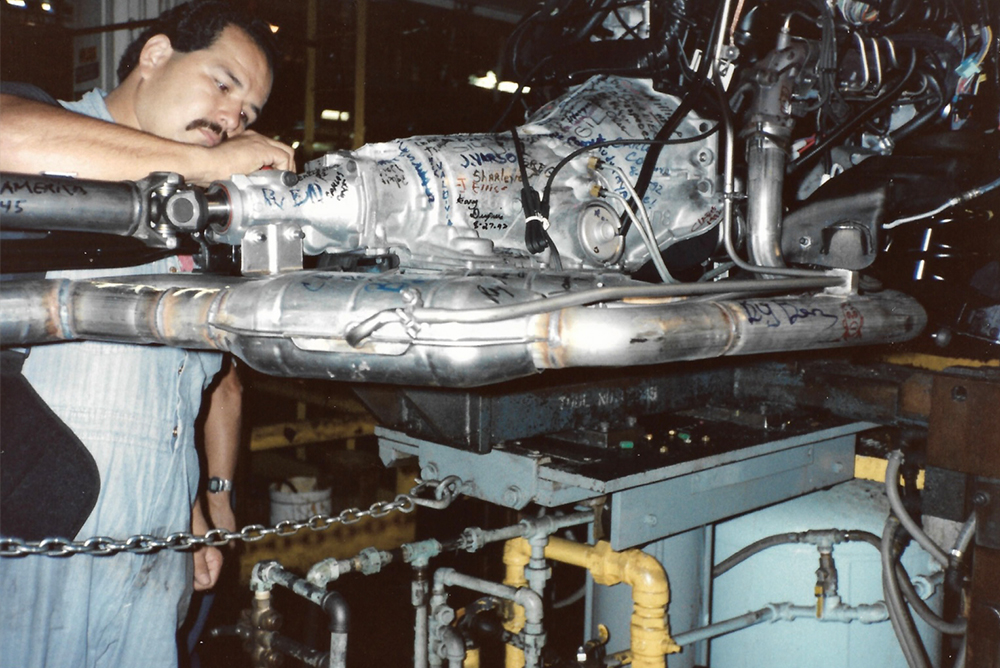

That evening, word spread about signing the car, and by the time Stevenson returned the following morning for the completion of assembly, he was greeted by many autoworkers who had previously turned in their badges. They’d all rushed back onto the floor to get a chance to put their own mark on the car. The drive shaft, the door panels, the transmission, the rear axle—all of it was signed. Painters left their marks, too, under the seat in silver paint, sealed in clear coat.

Overall, Stevenson estimates that more than 2,000 people signed his Camaro. In the weeks that followed, others sent him newspaper articles about the plant closure, and photographs of his visit. They wanted the last car to be a memento of what that plant had meant to them and their community.

The auto industry’s demise marked the beginning of the end of the Valley as a labor town. Automotive plants in L.A. suburbs of Pico Rivera, South Gate, and Commerce had all closed within the prior two decades; the Van Nuys Plant was the last facility standing.

Today, the Valley retains its outsider L.A. status in personality, but with the exception of the film and television industry, the working-class prosperity offered by those union jobs has vanished—as it has nationwide. As of 2022, the median home price in the San Fernando Valley sat at a whopping $901,500, out of reach for blue-collar workers.

When you talk to Stevenson about his trip to Van Nuys, it’s obvious how much the experience defined him. Over the years, he has reconnected with some of the autoworkers who made (and signed) his ’92 Camaro, and with the children of those autoworkers. “It’s brought me close to so many different people for different reasons,” he says.

To this day, former Van Nuys plant workers, who now live all over the country, have maintained communication via a 500-plus member Facebook group. They share former coworkers’ obituaries, and try to shore up missing connections, attending occasional in-person reunions and distributing commemorative T-shirts to keep the kinship and solidarity of their time at the plant alive.

The Last Camaro’s license plate is inscribed in their honor: 4UAW645—For United Auto Workers Local 645.

Send A Letter To the Editors