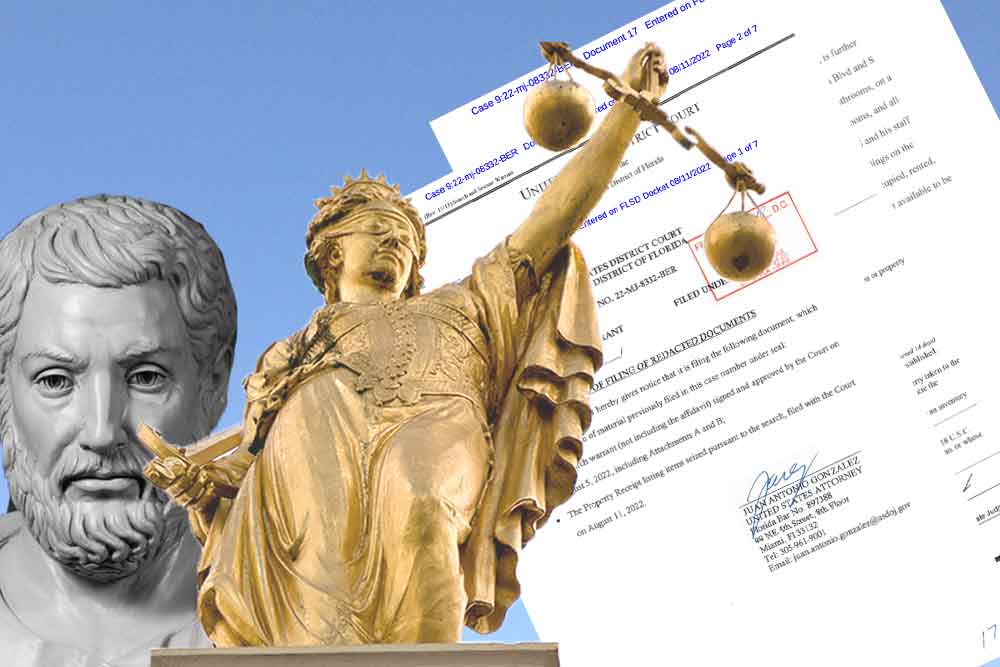

Asha Rangappa and Jennifer Mercieca trace the use of the Athenian concept of “isonomia”—equality under the law—and argue that the foundational democratic principle applies even to ex-presidents. Images (Golden Lady Justice, Cleisthenes, and search warrant) courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Illustration by Zócalo.

“All Americans are entitled to the evenhanded application of the law,” Attorney General Merrick Garland assured Americans on August 11, 2022, following the FBI’s execution of a search warrant at the home of former president Donald Trump. But partisan commentary surrounding the Justice Department’s unprecedented step has twisted that very same principle. The refrain of Trump’s supporters—“If they can do this to Trump, they will do it to you!”—sounds a lot like a threat. But it isn’t a threat. In fact, it’s a 2,500-year-old democratic promise.

What does “equality before the law” mean, where does it come from, and why does it matter? The ancient Greek term for Garland’s sentiment is isonomia, a concept which was rooted in democracy itself. Is a former president subject to isonomia? If the rule of law means anything, the answer must be yes. The law must be applied without fear or favor—equally to all—and that includes the former president.

Historians trace the idea of “equality before the law” to the magistrate Cleisthenes, whose democratic reforms to the Athenian constitution in 509 BCE ended tyrannical and aristocratic rule. According to Aristotle, Cleisthenes ushered in what we think of now as the golden age of democracy, which flourished at Athens—despite a few oligarchic interruptions—for nearly 200 years.

While historians associate Cleisthenes with “democracy” (dêmos = people + kratos = power), he called the government he created isonomia (isos = equal + nomos = law, custom). Isonomia for Cleisthenes seems to mean both the equal right to participate in making the laws and the equal application of the law to every Athenian citizen.

In fact, isonomia occurs in Greek political thought before democracy does—equality before the law is such an essential element of democracy that the political system could not exist without it. Herodotus, in the earliest known use of the word demokratia, invoked isonomia in an imagined debate defending democracy: Equality meant every citizen was eligible for office, all officers were accountable to the people, and all citizens had an equal right of free speech (isēgoría) in the Assembly. These were also the features of Greek democracy, essentially equating the two.

Political theorists and governments over the past 2,500 years have generally agreed. Cicero, then Livy, then British Whigs like James Harrington and Edward Coke and liberal political theorists like John Locke and David Hume, all invoked isonomia as fundamental to good order, political stability, and liberty. In 1960, the legal theorist and free-market economist Friedrich von Hayek explained how the concept moved from ancient Greece into the English common law tradition as the essential element of libertarianism—and the fundamental grounding of both British and American legal and political theory. In 16th-century England, Justicia—a.k.a. Lady Justice—began appearing with a blindfold, initially as a symbol of the judicial system’s turning a blind eye to those who abused the law, but eventually evolving to symbolize impartiality before the law. And while the United States struggled to perfect racial equality in practice, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which was ratified after the Civil War, enshrined it as a democratic aspiration by guaranteeing, “No State shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Law students today still learn the word isonomy, and as Attorney General Garland explained, it’s still the standard to which we hold our laws and our government. But its application to the person occupying the office of the president has, historically, presented some thorny problems. The presidency comes with vast powers, unique privileges, and unofficial immunities. For example, the Constitution entrusts the president to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” making him the top law enforcement official in the country. The most extreme reading of this phrase could suggest (as some argue) that this power allows the president to start and stop investigations at will … including those into himself. (This idea was summed up by President Richard Nixon’s maxim, “When the president does it, it’s not illegal.”) Presidents can also invoke executive privilege, which acts as a constitutional protection against the legislative and judicial branches overreaching into core presidential functions. In theory, executive privilege should ensure the robust and efficient operation of the executive branch—but it can also be used as a shield by presidents inclined toward lawbreaking. Finally, for the last 49 years, the Justice Department has refrained from indicting a sitting president, under the theory that he has so many important duties that it would harm the nation if he had to focus on defending himself at trial.

Whatever temporary get-out-of-jail-free card the presidency might afford, however, disappears as soon as the person is no longer president. The legal perks belong to the office, not the person—and this is the part that seems to be lost on the former president. He repeatedly has claimed executive privilege and the power to declassify documents, and implied that he has immunity from prosecution. Trump has what we might think of as a “Pigpen” theory of the presidency. If we imagine him as the Peanuts character, Trump believes that a cloud of executive power continues to surround him, even though he left office more than 18 months ago. But there is no legal basis for that belief. If Article II power followed ex-presidents around for the rest of their lives, we would effectively have as many “presidents” as we have living former presidents. And in this case, Cleisthenes, who instituted ostracism to expel any citizen who threatened democracy, would likely have any living former president ostracized from the United States in order to maintain equality.

The National Archives made a Cleisthenian legal argument in its May 10, 2022, letter to Trump about the documents at Mar-a-Lago. In rejecting Trump’s claim of a “protective assertion of executive privilege,” the archivist explained that there was no precedent for an assertion of executive privilege by a former president against a sitting one. Trump is just an ordinary guy now, and the law applies to him, just like anyone else.

Equality before the law is an indispensable pillar of a democracy. It is the concept in which liberty is fundamentally grounded and the basis of our legal and political theory. There is no individual who is above the law, not in a government based on the rule of law. The principle of “equality before the law” means precisely that: If the government can search your home for stolen government documents, then it can also search the former president’s home for stolen government documents. That’s isonomia, that’s democracy.

Send A Letter To the Editors