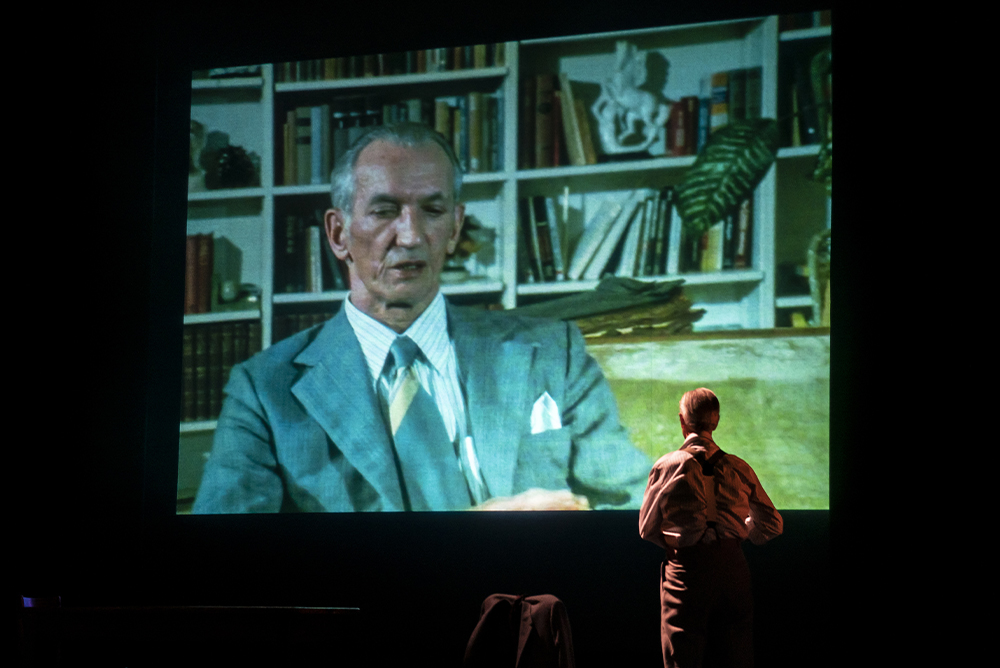

During a performance of Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski, actor David Strathairn, playing the titular character, watches an interview from the 1985 documentary Shoah in which the real-life Karski recounts his efforts as Polish Resistance fighter during World War II. “The play,” writes Justine Jablonska, “is a powerful reminder of Karski’s principles—truth and valor in the face of forces more powerful than you.” Photo by Rich Hein.

A man leaps into the air. The theater audience gasps, then relaxes as he safely lands. Jan Karski—scholar, diplomat, World War II Polish Resistance fighter, and the messenger who brought news of the then-secret Holocaust to the world when there was still time to stop it—has just escaped from Gestapo custody into the literal arms of Polish Resistance fighters, who will nurse him back to health.

The actor playing Karski, David Strathairn, tells the audience in Karski’s melodious Eastern European accent that after the escape, the Gestapo rounded up 100 Poles in retaliation. And executed 32 of them.

“Thirty-two lives for his one,” the play’s co-author, Clark Young, told me—describing the scene as a “profound moment of failure and trauma” for the protagonist.

The burden of Karski’s mission was tremendous, Young and co-author Derek Goldman highlight in their one-man play Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski, which opens off-Broadway this month. The show debuted in Washington, D.C. in the fall of 2019 and played at the Chicago Shakespeare Theater in the fall of 2021, which is when I saw it.

The play is a powerful reminder of Karski’s principles—truth and valor in the face of forces more powerful than you. The playwrights have shared Karski’s life and work with students at Georgetown University, where the real-life Jan Karski taught international relations. They and inclusive pedagogy specialist Ijeoma Njaka have been teaching a course focusing on the play since 2020.

During the play, the character of Jan Karski lands safely after jumping from a third-floor window to escape Gestapo custody. Photo by Rich Hein.

“It’s the kind of thing that truly inspires students, to see there is value even when you ‘fail,’” Young said. And Karski’s “failure” was truly profound: When world leaders did not act upon the proof of the Holocaust Karski delivered, millions died.

Like Karski, I was born in Łódź, Poland, and I also ended up in America, as he did after the war. When two childhood friends invite me to see Remember This in Chicago I initially balk. I struggle with the Polish part of my identity, distressed by developments in my homeland. But I revere Karski, so I go. And I am deeply grateful. Words and truth and witness—always an indelible part of my core—are so important, particularly today.

Jan Karski was born in 1914, and trained as a soldier and diplomat. He joined the fledgling Polish Resistance at the onset of World War II, after Poland was attacked by both Germany and Russia. Karski worked as a courier, delivering messages about clandestine German and Russian operations to the Polish government-in-exile in London. In late 1940, he was captured by the Gestapo and tortured for three days. He feared he would reveal secrets and tried to kill himself. The Gestapo took him to an army hospital, where he recovered from his suicide attempt and then escaped, a pivotal scene in the play.

Remember This opens in early World War II, when Germans established the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw, forcing one-third of the city’s population into a section comprising just over two percent of its area. Leaders of the Jewish Underground arranged for Karski to enter the ghetto so he could report what was happening to the Polish government-in-exile, as well as to British and U.S. officials. He and Jewish and Polish Resistance fighters believed that if they told the world—if the Powers That Be realized what was happening—they might stop it.

Karski visited the ghetto twice in 1942 and saw the horrors we today know all too well: starvation and death and decay. Disguised as a camp guard, he later entered a transit camp from which thousands of Polish Jews were transported to Belzec death camp.

In 1943, Karski traveled to London and Washington to meet with Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Karski was told Churchill was too busy; he was passed off to the British foreign secretary. Karski met with FDR—who addressed him as “young man” and inquired about the fate of Poland’s horses, but did not ask a single question about Karski’s horrifying news about German Nazi death camps.

“You will tell your leaders that we shall win this war,” FDR told Karski. “The United States will not abandon your country.” But as we know, as Karski and the Jewish and Polish leaders would come to know, as the millions slaughtered would come to know, FDR and Churchill did not act to stop the Holocaust.

After his meeting with FDR, Karski stayed in the U.S. He published a memoir in early 1944, and earned his PhD from Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service eight years later.

He taught at the university for 40 years, but did not speak publicly about his war activities for decades, until Claude Lanzmann interviewed him for the Holocaust documentary Shoah in 1985. In his first appearance in the film, Karski is silent for a few beats, breathing deeply. “Now, I go back,” he says. But he cannot. He breaks down and walks off screen. The trauma that still haunts him is painfully clear. Then he returns, and speaks.

In the documentary, Karski details his work with Szmul Zygielbojm, a Polish Jewish leader who figures prominently in the play. In a poignant scene, Karski reads a letter from Zygielbojm, written after the Warsaw Ghetto has been destroyed and most of Zygielbojm’s family has perished. Zygielbojm is anguished but still believes something can be done. “The responsibility for the crime of the murder of the whole Jewish nationality in Poland rests first of all on those who are carrying it out, but indirectly it falls also upon the whole of humanity, on the peoples of the Allied nations and on their governments, who up to this day have not taken any real steps to halt this crime,” the letter—a suicide note, it turns out—reads.

Zygielbojm hopes his final act of protest will finally spur action. But it does not.

A photo of the real-life Jan Karski on screen while the actor David Strathairn as Jan Karski stand on stage. Photo by Rich Hein.

That’s something that the Georgetown students passionately debate, Georgetown’s Njaka told me: What does it mean to tell, speak, live the truth in the face of such monumental opposition? They also discuss witnessing trauma that isn’t one’s own, especially relevant in many students’ passion for racial and social justice, she said.

It’s relevant to me too, and is why the plays affects me so.

Karski died in 2000. A decade later, I arrived in D.C. to attend journalism school and then went to work as a content director at the Polish embassy—where Karski had stayed when he came to warn FDR. I felt his presence everywhere: in the embassy’s hallways; in the robin’s-egg-blue main room where we held events and where he sits during the interviews I viewed on YouTube. On the anniversary of his death one hot July afternoon, I accompanied embassy officials to lay a wreath at his grave, on a sloping hillside in Mount Olivet Cemetery. The stone is stark, with just his and his wife’s names, and dates of birth and death. I also visited his memorial bench at Georgetown University—where Njaka held some of her classes on Karski this past fall.

When I watch Remember This, it is my first time in a theater since the pandemic began, and I am spellbound. I scribble notes in my program. I also weep—for Karski and his courage; for the Resistance fighters who helped him over and over again; and for today’s Poland: this small country that matters so much to me and my fellow Poles, but probably not to many others. I think about how one of the greatest sins against humanity was perpetrated on our soil and how terrible that legacy is. I think about the trauma that is so deep within those of us whose families were killed, and in those of us whose families survived.

Today’s Poland has veered away from Karski’s message of unity, humanity, and hope, embracing antisemitism and nationalism, declaring that the LGBTQ+ community is “an ideology worse than communism,” and enacting oppressive anti-choice laws.

Maybe this is why the current Polish government’s cruelty feels especially atrocious to me: You know better, I think. You know what it means when you define and vilify one part of a population as Other. You know what it means when people who can help, don’t.

At the end of the play, Karski says—about all he’s seen, all he’s witnessed: “It haunts me. And I want it to be so.”

I too was, and am, haunted. And I too want it to be so.

Send A Letter To the Editors