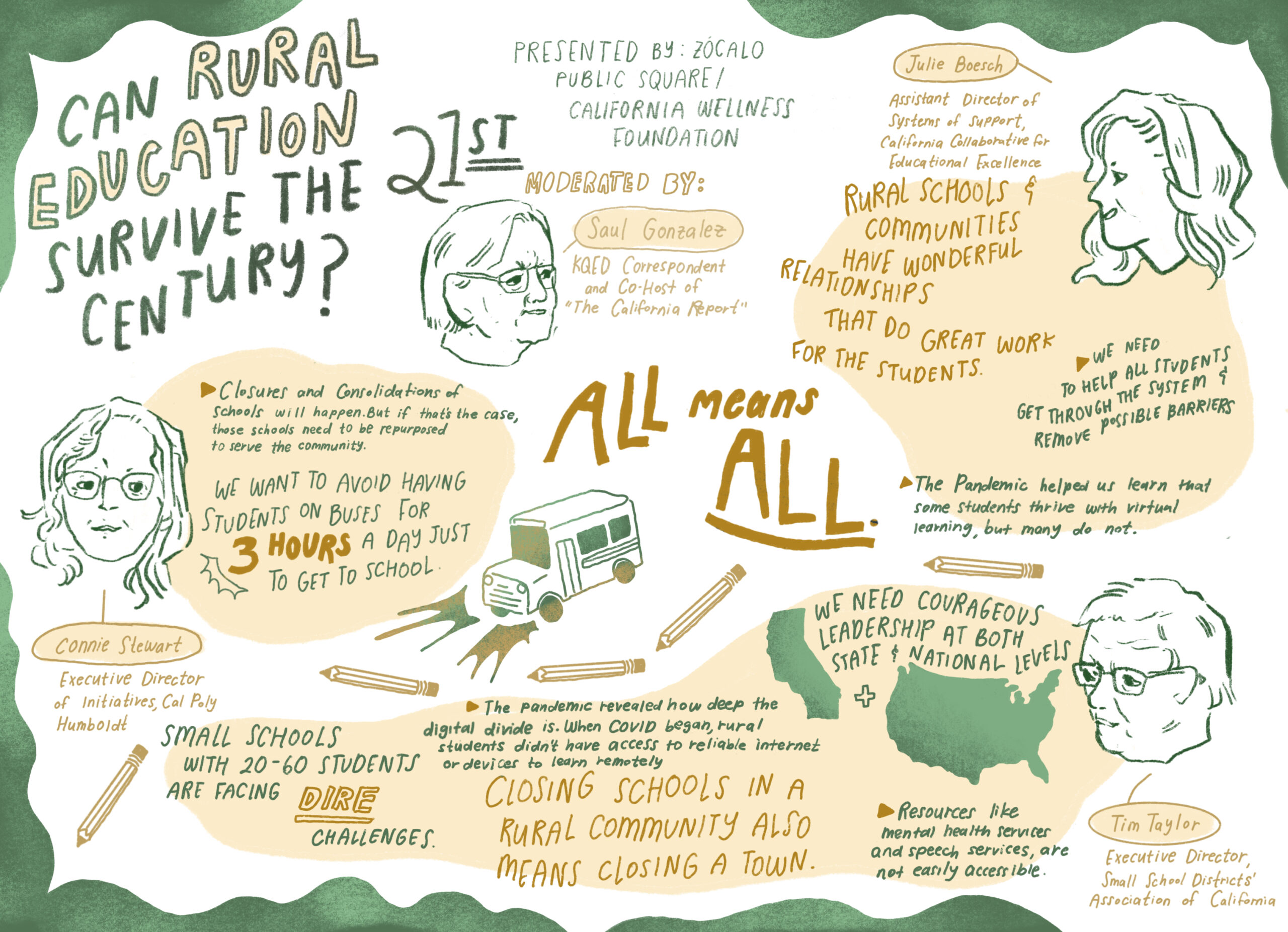

From left to right: Saul Gonzalez, Julie Boesch, Connie Stewart, and Tim Taylor.

When it came to the title question of the Zócalo/California Wellness event, “Can Rural Education Survive the 21st Century?,” the panelists were of one mind. Speaking to the live audience in downtown Bakersfield, their answer was a resounding “yes.”

But the discussion focused on a more specific query: How can rural education thrive?

In answering that, three veteran educators from different rural parts of California—Connie Stewart of Cal Poly Humboldt, Julie Boesch of the nonprofit California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, and Tim Taylor of the Small School Districts’ Association—offered several suggestions as they shared the stage at the Bakersfield Music Theatre.

The pandemic was a major topic of conversation, and the event’s moderator, Saul Gonzalez, KQED correspondent and co-host of “The California Report,” started by asking how it changed rural education.

Boesch, former superintendent of Maple Elementary School District in Kern County, called the past few years “a phenomenal learning experience.”

Yes, she said, it was difficult when, say, half of her small staff were out or exposed to COVID. But the “beauty of being small and rural” is that they also had “big opportunities to shift gears” to meet their students’ needs. With fewer than 300 students, she knew every child, and could figure out how to support them personally if they were struggling.

“In a small district like mine, I know everything going on,” said Boesch, who recently became the assistant director of services at California Collaborative.

Boesch said Maple was fortunate to get Chromebooks within a week of COVID, speeding the transition to distance learning. But this change wasn’t easy for many rural school districts, whose students ended up offline for quite some time.

Taylor, executive director of the Small School Districts’ Association, which represents and assists districts of fewer than 5,000 students, said when “March 13, 2020”—the day when schools were shutdown statewide by COVID—hit, it “exposed the whole digital divide issue.” “Our institution worked with the Department of Education to figure out how many kids didn’t have a device—let alone internet, let alone a hot spot,” he said. The answer was “hundreds of thousands.”

Stewart, executive director of initiatives at Humboldt, the newest Cal Poly campus, called the pandemic a necessary wakeup call. One of the changes it spurred was California’s recent $6 billion investment to expand broadband infrastructure. “The nice thing about COVID was it was all hands on deck—and it brought to light some of the issues around technology.”

“I’m very hopeful in the near future,” she continued, in a decade or so, “we’ll solve the digital divide.”

But equity issues run far beyond broadband for rural schools. Panelists agreed that, though one in four students in the United States today attends a rural school, state and federal lawmakers are not spending one-fourth of their time thinking about these kids, much less visiting their schools.

“Rural doesn’t go to Sacramento enough, and Sacramento doesn’t go out to rural,” Stewart said.

Boesch recalled how, when she first arrived at the Maple district eight years ago, the rains were so bad that there was water coming through the walls. It took years of lobbying officials outside the district, and the building of bipartisan support in the legislature, to fix the issue.

“I put 40,000 miles on my car advocating for my communities. That’s what it takes,” Boesch said.

More attention is required because the challenges in rural districts are different, panelists said. And getting more attention requires behaving more like urban school districts that go to the media, and to court, to make sure their needs are addressed.

“We need to follow the blueprint of urban schools to tell their story for what their children are up against,” said Taylor. “We don’t do that. And we don’t litigate.”

Panelists say rural schools have to get creative to provide services. Boesch shared how she was able to afford a school psychologist by splitting their salary with a consortium of other rural schools. That required negotiating a memorandum of understanding between each school, and finding an employee who was willing to serve everyone.

Rural schools don’t just lack supportive services; they also lack access to courses that help students prepare for colleges, such as AP classes.

But schools can compensate. “I came here to talk about solutions,” said Stewart, who encouraged high schoolers to dual enroll in community college in their areas. “Wouldn’t it be fabulous if every high school student graduated with some units at a community college? Wouldn’t it be fabulous if they all graduated with a head start?”

Students should also be encouraged to try a trade in high school, so they get to do “something they love” and learn about future job prospects.

What if there aren’t enough kids to run a school, asked Gonzalez, the moderator. When does it make sense to consider a closure or consolidation?

Students’ needs, not financial ease or consolidation plans, must come first, Boesch argued. “We have to serve all children,” no matter where they are, she said. If schools are closed permanently and the only choice left for students is to bus three hours to the nearest school district or solely virtual learning that’s putting barriers in place for their education when “it’s incumbent on us to remove barriers,” she said.

Stewart agreed, arguing for great care in such decisions. “We have to be smart about how we consolidate schools,” she said. If schools must be closed, then the next question becomes what we do with them so they’re still a benefit to the community. There are other educational needs that can be served, she said, citing successful second lives as community centers and bilingual centers.

Gonzales asked the panelists if they think there’s “a cultural bias against rural education.”

Yes, they said, but the nature of the bias may be changing. That’s because it’s no longer inevitable that people will move to urban environments. The pandemic saw people leave urban environments.

Climate change, Stewart added, is also shifting the conversation. She cited her employer—and its transition from being California State University Humboldt to Cal Poly Humboldt, with the resulting emphasis on science, technology, and the green economy— as proof of that. As a Cal Poly, Humboldt can encourage students to come not just to study but also to make lives and careers for themselves in rural Northern California.

But making space for people in rural parts of the state will only be a successful strategy if new arrivals can afford to live there.

Once upon a time, educators who moved to rural school districts were able to afford to buy their house on their salary. Now, housing prices having risen so rapidly that that’s no longer the reality for many, panelists said.

“The American dream is slipping from people in education, and we have to address that as Californians,” said Stewart. That’s why, she said, her organization is working to invest in workforce housing “so we can try to keep teachers” in the communities they serve.

Near the event’s end, Gonzalez asked the panelists to talk about the joys of small-town education. We’ve talked about the hardships, he said, but “what rocks about it?”

All the panelists spoke up at once.

It’s great to be well-known in your community, said Boesch: “We’ve seen generations of families go through school.”

It’s the ability and freedom to innovate, said Stewart: “All of us have wonderful stories of how we can quickly make change and that’s the beauty of being able to work at a rural school.”

And it’s the intimacy, said Taylor: “The school is the town. You’re part of this incredible loving, warm safe environment.”

Send A Letter To the Editors