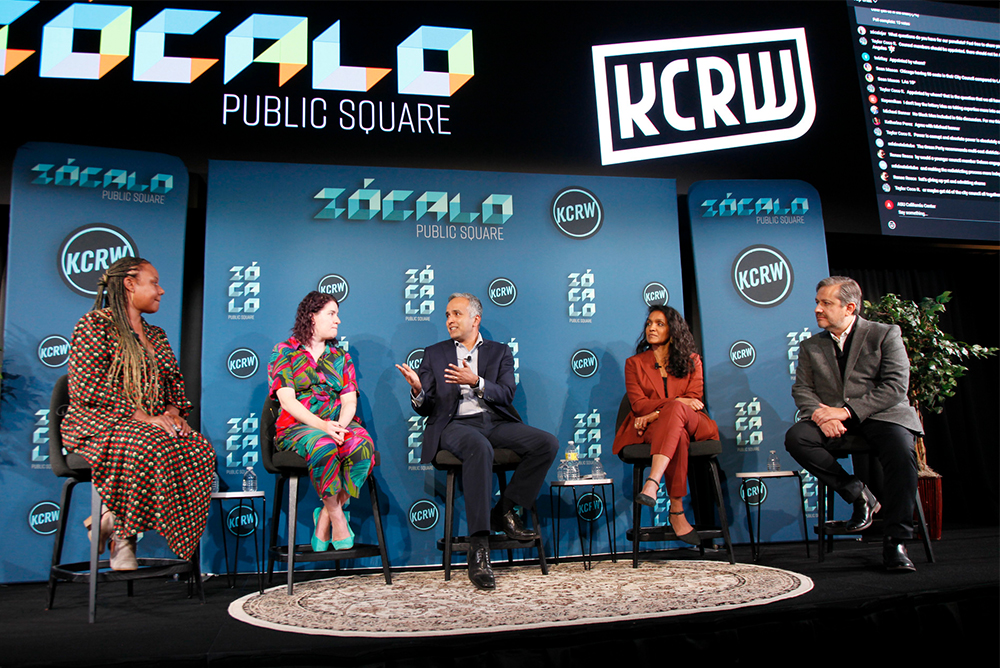

From left to right: Janaya Williams, Leonora Camner, Karthick Ramakrishnan, Nithya Raman, and Miguel Santana.

“Do we even need a city council?” That was the provocative title question posed at last night’s Zócalo/KCRW event at the Herald Examiner Building in downtown Los Angeles.

To get at the answer, a panel of democracy experts and L.A. political insiders discussed the history and future of L.A.’s embattled city council—and why, in this moment of pain and division, there’s a real opportunity to demand change in the way the city is run.

Moderator Janaya Williams, KCRW’s host of All Things Considered, started off the conversation by addressing the elephant (or, as she put it, the “two slightly racist elephants who will not stand down and resign”) in the room: councilmembers Kevin de León and Gilbert Cedillo. The legislators have ignored calls to step down following a leak of their conversation with the now-former council president Nury Martinez, where they were captured on tape using racist, crude, and homophobic language while conspiring to expand their political power.

“I was appalled at the remarks that I heard, embarrassed for the body that I serve on, and sad for Los Angeles,” said L.A. city councilmember Nithya Raman, who called on Cedillo and de León to step down before the scandal encourages “more pain and more division to form in the city.”

The leaked recording, she said, was all about power. But not, as her colleagues alleged, about consolidating Latino power; this was about consolidating their own, personal grip on L.A. “The more we focus on that, and the more we talk about how we can change processes in the city so that we don’t have a repeat of that kind of divisive conversation again, I think that to me is the way forward.”

Weingart Foundation president and CEO Miguel Santana agreed with Raman. This was a conversation about hoarding power, he said, something that he called “an L.A. tradition.”

“It wasn’t unique—it’s happened generation after generation, and in many ways, the city was founded on those principles,” he said. That’s because Los Angeles matured at a time when redlining—the systemic discriminatory practice of denying housing loan applications and other services based on race or ethnicity—was “the law of the land,” which meant that the majority of the city couldn’t buy property. Systems of governance at the time echoed this—“it was all about maintaining the privilege of some at the expense of others.”

Santana finds himself invigorated by the ways that Angelenos are reckoning with this reality in real-time today.

“It is very powerful to see all of Los Angeles react the way Los Angeles has,” he said. “To see the public testimony—20% of it being done in Spanish—to see folks say this isn’t the Los Angeles that I know, that I love, that I want us to be. And demanding that we do something dramatically different.”

But what should our new vision for Los Angeles be?

Public Access Democracy director Leonora Camner argued that we can’t just elect our way out of this situation. “Power is corrupting, even for people who have the best intentions.”

Instead, she suggests we think about the best ways to make a more democratic system. “There are a lot of exciting opportunities for us to do more experimentation and try out more innovative forms of government that really get to the heart of the problem,” she argued.

For instance, Camner said, we can think about using democratic lotteries that engage a representative cross-section of the community. “They elevate expertise more because people impartially listen to expert opinion when deliberating, without the worry of re-election,” she said.

This is something we already do with juries, and there’s a reason for that: “If you were on criminal trial and your fate was on the line, you’d never want that to be a political process,” she said. You’d want the process to be guided by facts and experts.

Why is it, California 100 executive director Karthick Ramakrishnan asked, that you can see innovation everywhere in California, but “not in the realm of democracy?” We can do so much more, he argued. He cited innovations from around the world, like Japan’s intergenerational simulations, in which half of the participants represent citizens in, say, the year 2050, and the other half represent citizens in the present moment. The groups have to come together and make decisions that serve both parties.

Whether solutions are old or new, we need to look at them with fresh eyes and determine what kind of political system we want, he argued. “What are the things we want to optimize for and encourage? What are the harms we want to minimize?”

Raman, too, pointed to existing innovations at the state level, the county level, and across America. “The question is,” said the councilmember, “if there is an idea we can consolidate around and how would you make it happen?” Among other issues, Raman said she’s especially interested in creating a “truly independent” redistribution commission and expanding the size of the city council.

Before the night ended, Williams asked all the panelists what they think L.A. would look like under a truly representative government. Would a city council be part of that picture?

“Maybe we’ll continue to have a city council,” said Camner. “But I hope that we make sure there are more opportunities for Angelenos to directly serve in some of these decision-making roles.”

Ramakrishnan called on Angelenos to “ground ourselves in core values—innovation, resilience, inclusion, and equity. These need to go from slogans to being operationalized.”

Santana pointed to the current urgency: “We need to reimagine it now,” he said. “We need to rely on those who have spent their careers thinking about these issues. We should give ourselves some permission and grace to imagine something different.”

And speaking from her role as a councilmember, Raman said she is heartened by how so many elected officials are now saying, “take away the number of my constituents, reduce the control I have over my district.”

This, she said, is “a revolutionary moment.”

Send A Letter To the Editors