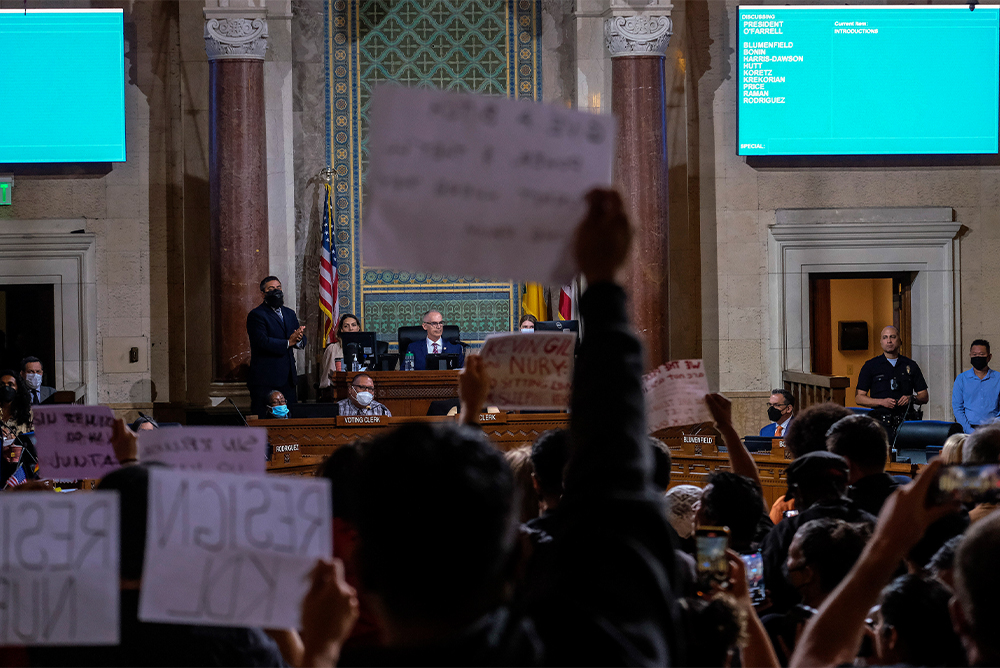

Former Los Angeles city councilmember Michael Woo reflects on the lessons he learned while running for and serving in office, and offers new rules of engagement for a more accountable and responsible city council. Courtesy of AP Newsroom.

Politics is full of high-stakes battles and strategies concocted behind closed doors. But that’s no excuse for the level of venality, toxicity, self-aggrandizement, condescension, hubris, and racism exposed in the leaked recording on redistricting that recently shook the Los Angeles City Council.

Nothing about the conversation—in which councilmembers Gilbert Cedillo and Kevin de León listened quietly as then-council president Nury Martinez spewed hate—was blatantly illegal. But it was shocking. It revealed deep hypocrisy among leaders who, in a public setting, would be the first to claim that they condemn racism and embrace the city’s diversity. It also violated an unwritten rule requiring a minimal level of decency in the way people treat one another.

Cynical observers might opine that decency can’t be expected from politicians. But treating others with respect (in private and in public) isn’t asking too much. As I learned during my own career on the council, basic decency is a requirement for getting things done in the public sphere. And today, new realities dictate new approaches to doing this unpredictable, messy, sometimes delicate, and wholly essential work.

Embracing diversity has been a constant in L.A.’s public discourse for the last 50 years, ever since Tom Bradley beat back incumbent mayor Sam Yorty’s efforts to use Bradley’s race as a divisive tactic in the 1973 mayoral race. Bradley was L.A.’s Black mayor, but he was never the mayor only for Black people. His rise to power represented a turning point in the city’s tortured race relations because it demonstrated that the people of Los Angeles were ready to transcend the politics of racial division—moving from “me” to “we.”

I came of age politically during the Bradley era. Growing up in the cities of L.A. and Monterey Park, I never experienced much in the way of overt anti-Asian bias except for the occasional unintentionally condescending comment about my lack of a foreign accent. (I’m a native Angeleno.) I became a candidate for the first time in 1981, running for L.A. City Council in a district where students at the local school, Hollywood High, spoke more than 40 languages and dialects.

I thought my background as the son of an immigrant would be seen as a plus. Instead, I observed my opponent, an incumbent councilwoman, use my ethnic identity to raise suspicions about my ability to represent a diverse constituency. I learned the bitter lesson that race can be a devastatingly divisive political weapon—even among liberal, sophisticated voters in a big city—especially when racial fears are linked to a receding majority’s economic insecurity.

I lost that first council race. But I came back four years later and defeated the same opponent, winning decisively with 58% of the final vote. I had learned a crucial lesson about the necessity of building multi-interest coalitions in a diverse city. Support from Asian Americans had provided me with a potent political base. But if I wanted to win in a diverse district, I had to reach far beyond the 10% of the population (and only 5% of the electorate) comprised of Asian Americans. I studied the intricacies of U.S.-Israel relations, spoke Armenian phonetically for a cable TV commercial, and learned why owners and patrons of gay bars in Silver Lake felt they were being harassed by LAPD officers.

It’s difficult to legislate decency—to require a minimal level of respect for other groups or individuals—because decency depends on having shared values that tell us how to act toward others, and that predict how others will act toward us. I learned, the hard way, that decency can’t be written into the legal verbiage of an ordinance or a charter amendment.

But I also learned to listen respectfully, and to talk respectfully, and I became comfortable crossing conventional boundaries. It served me well during my council years, when I sometimes became an unexpected messenger, speaking out on behalf of Central American political refugees seeking sanctuary, Latino street vendors trying to earn a living, and African Americans demanding justice and accountability in the face of police misconduct. During a very uncomfortable period when the city’s elected leaders were struggling to respond to the LAPD’s brutal beating of Rodney King, an unarmed African American motorist, I became the first voice in City Hall to publicly call for the resignation of the chief of police.

The fact that I was neither Black nor white made a difference because it meant that police misconduct was more than a Black versus white issue. It sent the message that doing the right thing was more than a matter of which tribe was in control or had the power to dictate the outcome.

Today, the rules of engagement I learned over decades in politics are in a state of flux. New rules apply.

First, the rise of micro voice recorders in mobile phones and watches, and instant dissemination of information through 24-hour TV news and social media, mean that the old boundaries between public and private no longer exist. A politician shouldn’t say or write anything, even in a private meeting or an email message to trusted associates, that they wouldn’t want to see splashed across the front of a newspaper, creeping across the bottom of a television screen, or retweeted.

The end of privacy comes at a cost. But it also may be the best guarantor of accountability, especially in an environment such as City Hall, where insiders tend to cover for each other and maintain a code of silence.

A second new rule applies to “bystanders” such as Cedillo and de León, who listened quietly to their colleague’s racist remarks. For those in the political arena, silence in the face of crude, demeaning, racist words is equivalent to concurrence. If someone says something deeply objectionable in your presence, even in a private meeting, you must express your disapproval, walk out, or otherwise end the discussion—immediately. This may be difficult, especially when it means confronting an ally in a position of power. But the current uproar shows that failure to object will be condemned later.

Los Angeles also needs to develop a new set of “ethics for ethnics,” rules of engagement for interactions between the emerging Latino majority and everybody else: African Americans (who maintain a substantial power base despite their declining population); Asian Americans (still underrepresented despite being the fastest-growing ethnic group in California); Jews; Armenians; other Middle Easterners; and whites, who retain a large share of power, influence, and resources.

Latinos make up nearly 50% of the city’s population but until last month held only four seats on the council. Their leaders today must define their obligations to themselves and to other groups. As they work to achieve better representation, what is appropriate for Latinos to acquire or aspire to as a political bloc? How do they address diversity among themselves? What is their obligation to other ethnic groups who are not as numerous but have real unmet needs? Can the city survive if the brutal, old school, winner-take-all, “grab-as-much-as-you-can-for-yourself-while-you-have-the-power” approach to leadership exemplified in the redistricting discussion prevails?

Arturo Vargas, longtime CEO of the National Association of Latino Elected Officials, recently called on Latinos to recruit a more diverse range of candidates for public office, going beyond the Mexican American and Cuban American core. This could go a long way toward addressing the intra-Latino rivalries (embodied in Nury Martinez’s crass comments about the stature and skin color of Oaxacans) that indigenous communities view as the default ploy of Mexican Americans striving to maintain their power.

But diversity in and of itself is not a solution. An underlying question remains about the quality of political leadership in Los Angeles: Does public office attract the best members of a community to seek leadership—and if not, how can we change that?

Perhaps aspiring leaders need better training, mentoring, and apprenticeships, or a wider range of career and life experience paths, to prepare themselves for the grueling demands of leadership roles. We also might consider whether there could be better ways to choose our leaders, so that those among us who actually believe in the fundamental values of our community can rise to the top.

Send A Letter To the Editors