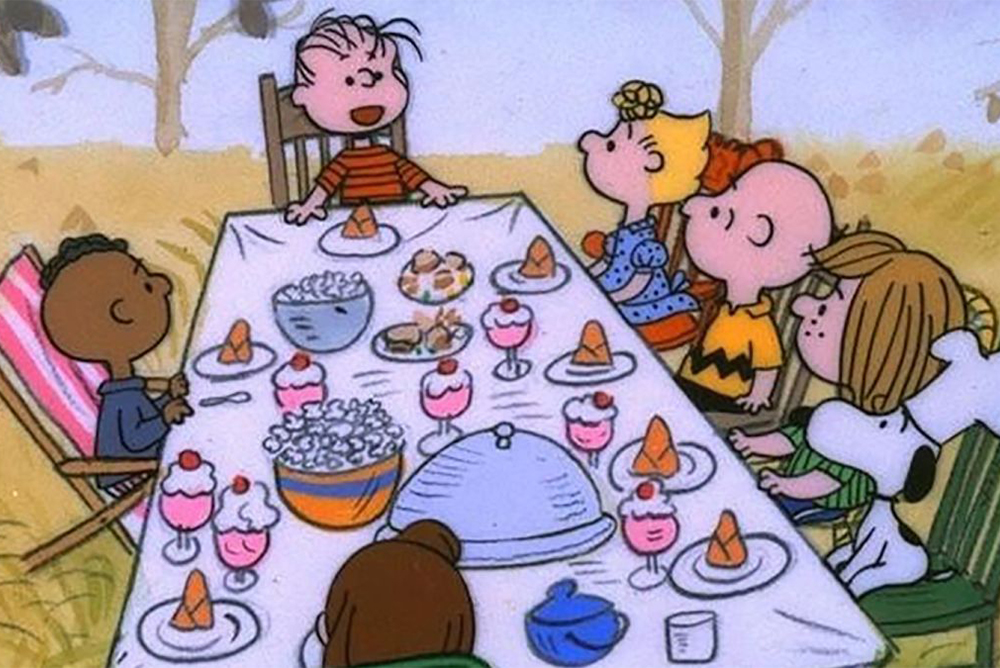

This November, give thanks (and raise a glass) to friendship. Courtesy of Warner Home Video.

Across the United States, group chats are blowing up. Who’s bringing dessert? A side dish? A casserole? The wine? More wine?

The discourse isn’t necessarily anchored to the fourth Thursday in November, and the people texting share neither DNA (nor deep-rooted emotional baggage). Rather, such pressing questions revolve around an unofficial holiday nominally in the Thanksgiving orbit that’s slowly formed its own customs and significance over the last decade or so to become a standalone celebration in its own right. The result, Friendsgiving, has become one of my favorite events on the calendar year.

Sometimes traced to November 1994, when the TV show Friends aired its first Thanksgiving episode, the concept was floating around for some time before the word “Friendsgiving” appeared in print circa 2007. The fledgling tradition received a boost four years later after Baileys Irish Cream used it in an ad campaign, and each November since, it has grown more popular, breaking through the American lexicon by the mid 2010s. (Merriam-Webster officially added the term to the dictionary in January 2020.)

But what if instead of thinking about Friendsgiving as a recent phenomenon, we considered it a welcome return to a time when our culture centered around friendship?

In classical philosophy, friendship was considered to be the summum bonum, or highest good.

That’s because the ancient Greeks and Romans viewed the relationship as a glue that held civic life together, uniting private and public spheres. As Aristotle once wrote: “Friendship or love is the bond which holds states together, and that legislators set more store by it than by justice; for concord is apparently akin to friendship and it is concord that they especially seek to promote.”

America’s founders also understood friendship in this light.

“Inspired by the Aristotelian concept of friendship as collective tissue, early Americans understood male friendships as crucial to the nation-building project and its creation of worthy republican citizens encouraging empathy between citizens in a society that no longer cohered through shared loyalty to a monarch,” as American literary scholar Michael Kalisch argues in The Politics of Male Friendship in Contemporary American Fiction.

Indeed, Kalisch contends that while the republic’s separation from Britain is often framed as a refusal of paternal authority, male friendship offered an “alternative metaphor of civic association in the nascent independent nation,” one that united it with France’s cry across the ocean for liberté, égalité, fraternité. Both revolutions, Kalisch posits, were “galvanized by the egalitarian promise of friendship”—even though, as he points out, such a promise only extended to white men.

But if ideas of friendship and love were long seen as interchangeable, friendship’s decline in the American civic space coincided with the separation of these spheres. In Perfecting Friendship, Dartmouth gender and literary scholar Ivy Schweitzer observes that by the late 1800s “the distinctions between friends and family, love and friendship gradually became clearer” and that, in turn, “friendship as the privileged site of sympathetic attachment became increasingly feminized, privatized, and removed from the public sphere of republican and democratic politics.”

In the 20th century, friendship remained on society’s periphery, Schweitzer continues, as “Western culture developed an obsession with individual selfhood and sexual desire.” So dramatic was the drop-off, she notes, that by the 1990s the American literary critic Wayne C. Booth confessed, while reading about Aristotelian friendship, “to be puzzled by the modern neglect of what had been ‘one of the major philosophical topics, the subject of thousands of books and tens of thousands of essays.’”

But the understanding of friendship as a civic model wasn’t abandoned wholesale during this period: Marginalized communities, in particular, continued to advance older notions of friendship, recognizing the ways in which it provided a powerful alternative mode of intentional community and organizing. In Feminism for the Americas, UCLA historian Katherine M. Marino shows how friendship was embraced as a model of social democracy during the rise of a global movement for women’s rights. Leaders like Panamanian feminist Clara González, Marino writes, understood that friendship corresponded “to the real needs of modern life, which is essentially a life of relationships, of interdependence, of solidarity, of mutual aid, of social action and of love.” The concept of the “chosen family,” first articulated in 1991 by anthropologist Kath Weston in Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship, illuminated the ways that queer and transgender individuals, too, had pushed the notion of friendship to encompass deep, deliberate bonds that existed outside of legal or genetic ties.

The rise of Friendsgiving from an ad hoc replacement for being far away from home on the holidays into a ritual all its own suggests we’re seeing a larger, mainstream push to celebrate and honor these non-familial social relationships. And I hope its popularity is an indication of broader willingness to reconsider the role that friendship can play in our society.

So, if you’re participating in a Friendsgiving of your own this year, consider if you’re advancing a model of friendship that the ancients might recognize. And maybe save a toast for Cicero and his treatise How to Be a Friend or Laelius de Amicitia, and cheers to the benevolentia (mutual kindness), consensio (consensus), caritas (devotion), and fidelitas (loyalty) that you’re cultivating together.

Send A Letter To the Editors