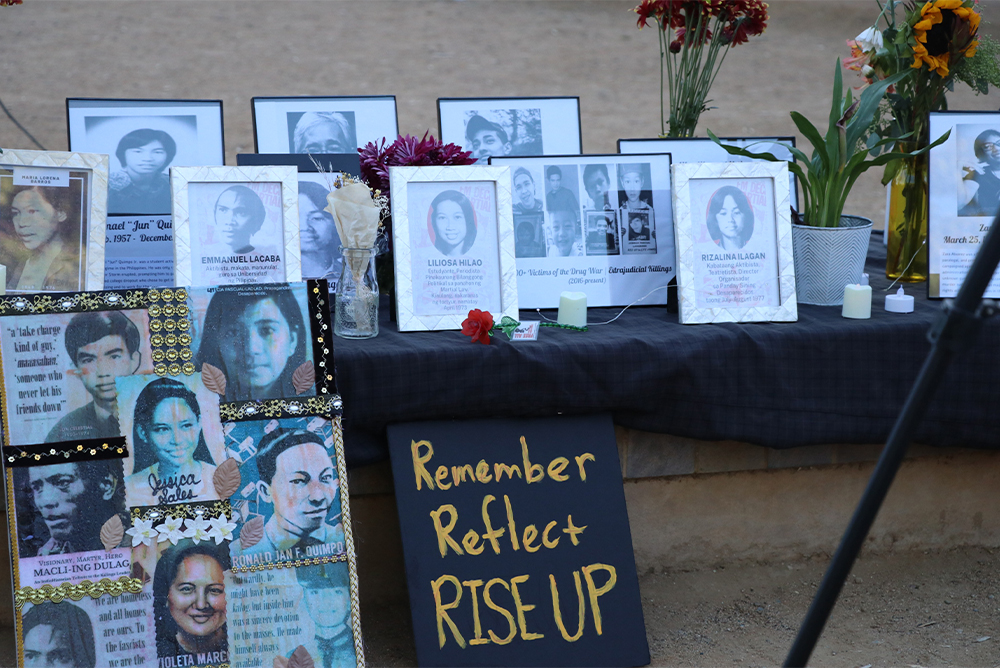

L.A.-based activists Valmina May and Joy Sales reflect on the bloody history of martial law in the Philippines, and their fight against the false narratives that have supported President Bongbong Marcos Jr.’s rise to power. Above: an altar dedicated to those who died opposing martial law, displayed at a rally at L.A.’s Unidad Park. Photo by Raine Gonzales.

The numbers—70,000 detained, 35,000 tortured, 3,200 killed—represent the victims of President Ferdinand E. Marcos Sr.’s era of martial law, from 1972 to 1986. They serve as a reminder of one of the darkest periods in the Philippines’ history.

That darkness is enveloping the nation and its diaspora once again. In May 2022, 38 years after his family was exiled from the Philippines in the People Power Revolution, Bongbong Marcos Jr. was elected to a six-year presidential term alongside vice president Sara Duterte, daughter of former president and authoritarian Rodrigo Duterte.

Marcos and Duterte supporters romanticize martial law as a “golden age,” but many Filipinos—including diasporic Filipino Americans like us—question or outright reject this distortion of history. This past year’s developments in the Philippines urge Filipinos and non-Filipinos alike to preserve and reinforce our historical memories of dictatorship. Indeed, the fight to preserve our historical memory goes hand in hand with the fight against fascism. Many Filipino activists reference the popular aphorism, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Only through a transnational movement of truth-based remembering and community organizing can we confront the present-day threat of the Marcos-Duterte administration.

When Marcos Sr. rose to power democratically in 1965, he posed as a populist—but made unpopular decisions. He supported the U.S. war in Vietnam, which allowed for the increased use of U.S. military bases in the Philippines; he devalued the peso relative to the U.S. dollar, increasing prices of basic goods and services for working Filipinos; and he violently put down student protesters who opposed his plans to run for a third term.

In 1972, under a questionable interpretation of the Philippine Constitution (ratified when the Philippines was still a U.S. colony), Marcos declared martial law to bypass the two-term presidential limit. Alongside the growing communist movement, opposition grew from multiple sectors of Philippine society exercising their right to political dissent: workers and peasants, youth and students, women, and Indigenous peoples.

Because martial law outlawed protests, activists organized underground to fight for social and political change. Their demands ranged from the restoration of civil liberties to winning a socialist revolution, but they all wanted to end the Marcos dictatorship, and they worked to end human rights abuses, such as political detention and torture, and to halt economic plunder, some of which came in the form of public works projects that violated Indigenous sovereignty.

Mass arrests, especially in the first years of martial law, caused many activists to flee the country and settle in major cities like Los Angeles. There they met like-minded Filipino Americans who were politicized by the civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, and the labor activism of Filipino farm workers who migrated as U.S. colonial subjects in the 1920s and ’30s.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Filipinos in the U.S. and their allies formed organizations such as the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino, National Committee for the Restoration of Civil Liberties in Philippines, Movement for a Free Philippines, and Friends of the Filipino People. They educated the broader U.S. public on the atrocities of the Marcos dictatorship, lobbied Congress to cut military assistance to Marcos, and raised funds to free political prisoners. Our activism grows out of this tradition.

U.S. presidents Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan supported Marcos; as part of the Mutual Defense Treaty, Marcos helped the U.S. maintain its security interests in Southeast Asia, and in return, Marcos received military aid. But eventually he became too great a liability. In 1986 hundreds of thousands of Filipinos joined the People Power Revolution, flooding the streets of EDSA Boulevard in Manila to protest Marcos’ attempt to steal the election from Corazon Aquino. Outflanked, the Marcoses fled to Hawai‘i via a U.S. Air Force transport plane.

Now, in a blatant act of historical revisionism, President Bongbong Marcos Jr. claims that the Philippines made economic and social progress under his father. But the data shows that Marcos Sr. left the Philippine economy in shambles. Over the years since, through subsequent presidents and large-scale land and agrarian reforms, widespread distrust in government combined with widening class divisions created the perfect conditions for the return of a fascist government via Rodrigo Duterte in 2016.

Duterte took pleasure in using violence to consolidate power. During his presidency, from 2016 to 2022, he urged civilians, law enforcement, and military alike to kill an estimated 30,000 Filipinos as part of a so-called Drug War, which he alarmingly likened to the Holocaust. Victims of the Drug War are still waiting for the Philippine government to cooperate with the International Criminal Court and hold Duterte accountable, while current president Marcos has promised to continue his predecessor’s campaign of terror.

Duterte also declared martial law for 60 days in Muslim-majority Mindanao, a historically resource-rich and war-torn region with the highest rates of poverty in the Philippines and a 400-year history of resisting colonial forces. Philippine presidents continue to receive support from foreign powers for these militaristic ventures. The U.S. gave the Philippines $600 million in military aid during Duterte’s presidency.

Activists at Unidad Park in Los Angeles’ Historic Filipinotown standing in front of the “Gintong Kasaysayan, Gintong Pamana (A Glorious History, A Golden Legacy)” mural by Eliseo Art Silva.

Faced with another era of fascist rule, activists with organizations such as Bayan USA and Malaya Movement USA channel the spirit of People Power. On September 20th (September 21st in the Philippines), we held a rally at L.A.’s Unidad Park in Historic Filipinotown to mark the 50th anniversary of the declaration of martial law—to remember the activists killed under Marcos and Duterte, to decry historical revisionism and Marcos Jr.’s visit to the United Nations that very day, and to encourage more people to join the movement. It is crucial at this time to remember accurately and to speak out against censorship and share fact-based news, since Marcos Jr., following his father’s example, has taken an aggressive stance against press freedom. And it is especially important for Filipinos and our allies in the U.S. to put pressure on the Biden administration to end support of the current Marcos administration through the Philippine Human Rights Act.

The fact that the Filipino masses, with support from progressive media and the U.S. Congress, could oust Marcos Sr. in 1986 suggests that we have the power today to prevent another period of dark and bloody history.

We have seen history repeat itself in a harrowing way with the return of the Marcoses to Malacañang, but we could see it repeat favorably with another mass movement of remembrance that can hold the Marcoses and Dutertes accountable for their crimes. In doing so, we can uplift the history of activism that brought an end to martial law and, drawing on that legacy of people power, build a genuinely democratic Philippines.

Send A Letter To the Editors