From left to right: Torie Bosch, Nonny de la Peña, Charlton McIlwain, and Ethan Zuckerman.

Will ChatGPT change the world? The new artificial intelligence chatbot, which has inspired both fear and awe with its power to do everything from write jokes and term papers to perhaps even make Google obsolete, would not be the first piece of computer code to fundamentally alter the way we live. It won’t be the last, either.

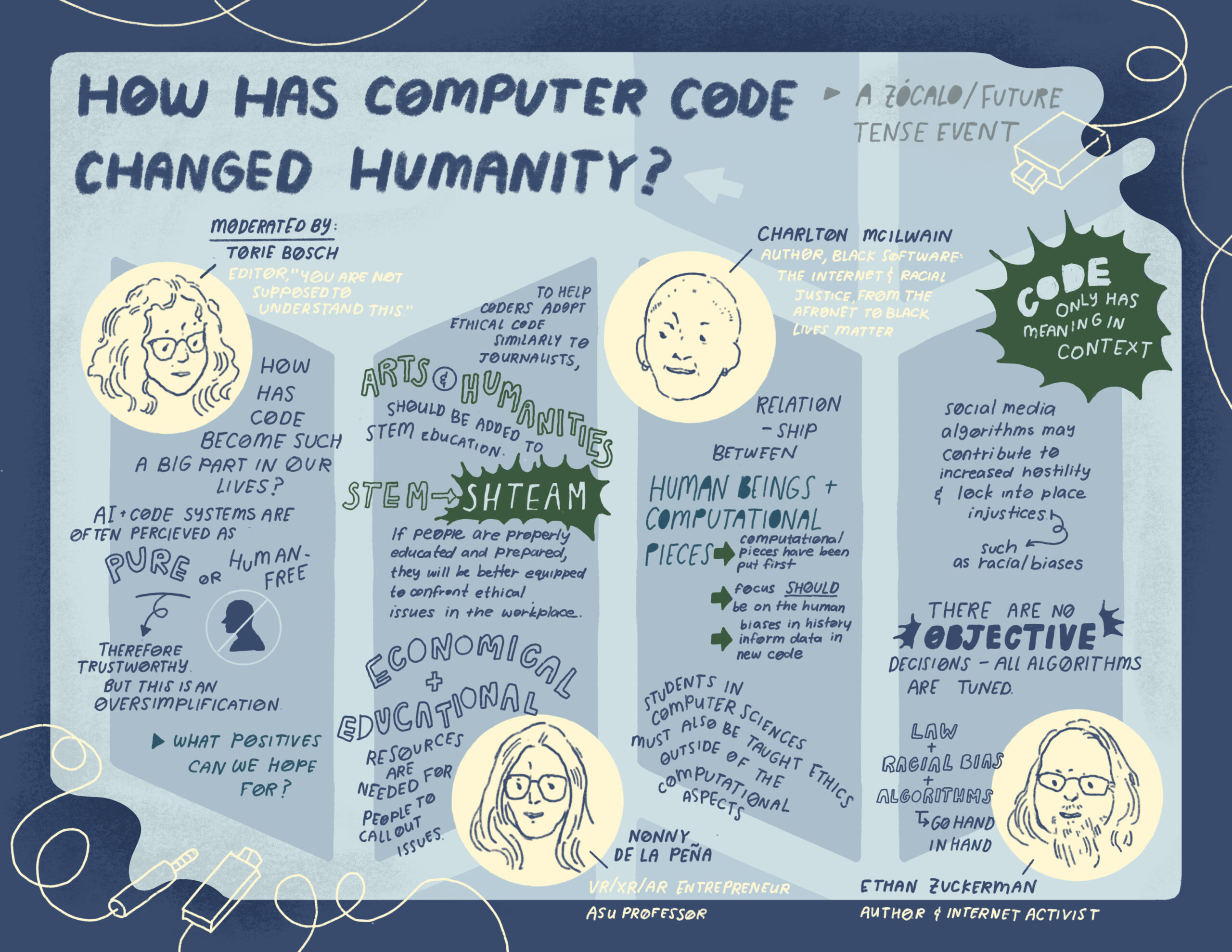

But even as we wring our hands over all the ways AI might replace humans, we tend to forget or ignore what Torie Bosch, editor of the new book “You Are Not Expected to Understand This”: How 26 Lines of Code Changed the World, called “the very human decision-making that goes into code.” Bosch, who is also editor of Future Tense (a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University), was moderating a Zócalo/Future Tense event that, like the book, was designed to help even those of us who know nothing about building software understand how the actual writing of code affects our lives and our world.

Bosch opened the discussion by asking a group of three tech scholars and makers to walk the audience, at the ASU California Center in downtown Los Angeles and watching online, through the process: How does a string of instructions tapped into a keyboard by a programmer—software, a.k.a. code—become ubiquitous in our everyday lives?

“I wrote a piece of code in 1997 that was really designed to solve a problem,” began internet activist Ethan Zuckerman—who contributed an essay to the book, and whose 2013 book Rewire won the Zócalo Book Prize. At the time, he was working at an early web hosting service. “This was the dawn of user-created content, and advertisers were uncomfortable,” said Zuckerman. “Did they want to be associated with random people’s content?”

He wrote code essentially creating the pop-up ad—ensuring that a brand would not appear on the same page as possibly objectionable material. He solved the problem, but eventually realized that he had erred when he hadn’t looked at the assumptions behind it: the belief that the internet—like magazines and broadcast media—had to be supported by advertisements that needed to grab viewer attention and monetize it. “I’ve come to think of [that] as the original sin of the web,” said Zuckerman.

What if he had instead asked if advertising really was the best way to support the internet? What if he and his employer had “looked at the internet as a public service?” Zuckerman wondered. “How often are engineers solving problems but not doing the work of asking, ‘Is this the right problem to solve?’”

Media, culture, and communication scholar Charlton McIlwain, who also contributed an essay to the book, shared a similar story—though in this case “about the intentional consequences of technology.” He recounted the Police Beat Algorithm, a piece of code designed in the mid-1960s to help police figure out where to place patrols in a city. The software was “ostensibly about solving and preventing crime”—but actually solved for “a problem of Black people … a group of people starting to amass power and challenge a system.” (In other words, the software was destined to send more police into low-income, Black and brown communities—and to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.) That algorithm ultimately created today’s global surveillance infrastructure and everything “from facial recognition systems to racial profiling,” McIlwain said.

But code alone doesn’t create problems, noted Bosch—the fact is that coding “reflects and shapes human values.”

Zuckerman said that algorithms for setting bail and prison sentences based on data from the existing criminal justice system “are now locking into code racial biases that have been plaguing our nation for decades.”

This isn’t surprising for a society that puts technology before people, said McIlwain. “Human values, human interest, end up baked into these technological products that we make because that is fundamentally where we live,” he said.

Bosch asked if educational institutions should be stepping in with ethics instruction, and McIlwain and Zuckerman both agreed that computer scientists and engineers need to learn more about the complexity of society before they try to solve its problems.

The third panelist of the evening, augmented/virtual reality entrepreneur Nonny de la Peña, a longtime journalist and founding director of ASU’s Narrative and Emerging Media program, agreed. She argued for adding the arts and humanities to STEM education—turning it into “SHTEAM,” and having coders adopt an ethical code as stringent as the one traditionally used by journalists and newsrooms. “It goes beyond ‘do no harm,’” she said. At an institutional level, she added, every city and county should also build “a technology board, like a water board” to treat tech more like a public utility, that doesn’t discriminate against or redline certain groups.

All three panelists discussed the complexity of putting the onus on programmers themselves to blow the whistle on big tech. McIlwain pointed to the tension between making big money or making the world a better place. Zuckerman said that the tech world needs to help ensure that people who do blow the whistle, like AI researcher Timnit Gebru (who was fired by Google after advocating for diversity and writing a paper on bias in AI), have a safe place to land.

Nonetheless, all three panelists are optimistic about the next generation of programmers, who, McIlwain said, “are not fraught with everything that’s wrong about the world, and who have found folks who are allowing them the space to imagine, to be creative, to give us a blueprint for what could be our future.”

The final question of the audience Q&A session—which also included back-and-forth about accessibility in tech and the possibilities of AI writing code—also addressed young people, and whether they can be taught to resist advertising in order to neutralize algorithms.

De la Peña, the mother of a teenage boy—“who experienced a lot of stuff coming at him from Alex Jones and other things fed at him on YouTube”—said that such education must “be real touch, not tech touch.” In her case, a one-on-one discussion succeeded, but the question remains how schools can address these issues.

McIlwain and Zuckerman both noted that systemic and structural change that goes beyond algorithms and individual choice is more likely to be effective. “It’s not too late,” said Zuckerman.

Send A Letter To the Editors