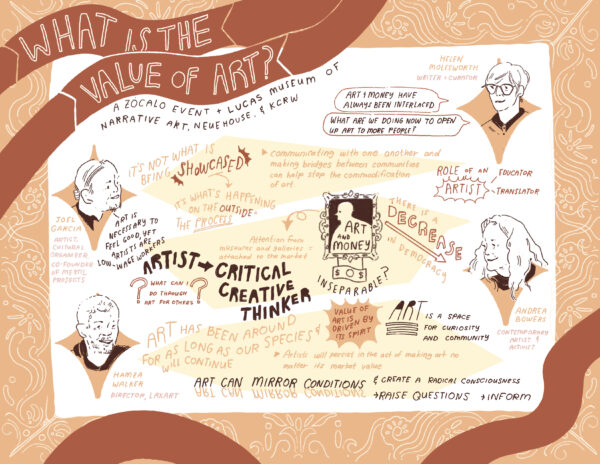

From left to right: Hamza Walker, Joel Garcia, Andrea Bowers, and Helen Molesworth. Photo by Chad Brady.

“L.A. is one of the largest creative economies in the world but artists here are low-wage workers. So do we even value art at all?”

Artist Joel Garcia asked the pointed question at last night’s Zócalo program, “What Is the Value of Art?” Put on in partnership with NeueHouse, KCRW, and Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, the program took place just days before Frieze Los Angeles—a week of art exhibitions, events, and big money—descends upon the city.

The panel spoke to a packed house at the ASU California Center. The conversation, moderated by curator Helen Molesworth, considered the long, entangled history of art and money in the West and what a decommodified art world might look like. They also interrogated the program’s premise—ideas of “value” and “art”—and found within it a space for curiosity and critical thinking.

Molesworth began by asking the panel to describe a formative work of art. For LAXART director Hamza Walker (who filled in at the last moment for his friend, CEO of Lucas Museum of Narrative Art Sandra Jackson-Dumont), it was the album covers that he encountered as a “young punk” in Baltimore. Artist and activist Andrea Bowers mentioned Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” which was on her mind because she recently learned more about the weekly potluck dinners the studio volunteers came to during the making of it. And Garcia, who is also a cultural organizer and co-founder of Meztli Projects, evoked the scene in Purple Rain where the camera pans in the crowd and you see the punks, the goths, and other folks coming together. “I want to be able to do that,” he said.

Hearing these examples, Molesworth observed that the panel was already opening up the traditional meaning of art: “It’s not ‘I went to the museum and saw Rothko and had to bow down.’ It’s being in community with others.”

This, of course, runs counter to the current media obsession with art that’s rooted in its market value. That connection isn’t new; art and money, Molesworth joked, have been in bed together in the West from their “Roman Catholic church marriage” onward. She turned to the panelists: Do you think the field is less tied to institutions and markets than it used to be? “What,” she asked, “is your hope meter at in this long game we’re playing with art? Because art really is a long game.”

“I want to believe it’s as-long-as-the-species-itself game,” Walker said. “We’ll continue to do it as long as we’re around. Market this, that, or the other. Good, bad, fact of life—I’m not bothered by it. It’s there. But it isn’t the end all, be all in any way whatsoever in terms of the gauge of the value.”

It isn’t about what’s being showcased at these art fairs, Garcia agreed, “it’s what’s on the outside of it.” He referenced the ’80s Chicano artist collective Asco who spoke of the unpopular in-between in the kinds of spaces where the “spotlight isn’t on [but] where a lot of the magic happens.”

Molesworth asked Bowers what she thought: “Do you see an increasing democratization of art or a decreasing democratization of art?”

Decreasing, said Bowers. “I see a decrease of democracy in general. I can’t separate art from capitalism. We’re stuck as artists and curators and directors in this f—ed up system.”

But there was a consensus among the panelists: if anyone can help change the current paradigm, it’s artists.

“We can create a new way of seeing things,” said Garcia. “We can create many worlds and where many worlds fit.” That’s why artists can take on the undefined and identify the gaps in systems and open them up in ways that aren’t rooted in white supremacy. Take the toppling of the Junipero Serra statue in Father Serra Park in downtown Los Angeles that Garcia witnessed firsthand. “Someone in policy may be so deep into it, they don’t see these points of intervention that artists can exploit,” he said.

What is it about art, Molesworth asked the panelists, that is so intertwined with justice and equity?

For Walker, what makes art so powerful is that it can mirror conditions, and by doing this, it can produce a “radical consciousness” of those conditions, if people let it. But rather than think about art in terms of solving social justice, he said that he finds it more useful to think about art as a space to ask questions: “Do I go to museums to look at art for solutions? To be honest in most cases, not necessarily,” he said. “I have to ask myself, what, if anything, am I looking for when I go to look at stuff? But there are those experiences that do inform me in terms of critical capacities, in terms of thinking that I don’t get through what I read in the newspaper.”

Art is not in the category of social justice, Bowers agreed; art is a category all its own. But as her passion and subject matter, she is constantly thinking through questions like, “how I can be of service, and what art can do?”

As the conversation came to an end, an audience member shared that when he first read the title of the event, money or commodification didn’t cross his mind. To him, the question was clear: “I thought of the value of art to people and improving society.”

Molesworth observed how, after an hour of conversation, that showed just how open to interpretation the value of art remains. It reminds us, she said, that one of the biggest “values” of art is that it gives us a “critical questioning relationship with those terms.” It’s important, she continued, to recognize that art plants seeds “not only of beauty and love but also of disrepair to break things that need to be broken and repair things that need to be repaired.”

That’s why art is “so valuable to all of us, and so crucial to all of us” she said, bringing the conversation to a close, because “it is so fungible.”

Send A Letter To the Editors