The postcard selection on Vis, Croatia’s most remote island, was not terribly appealing. I considered a card adorned with a photograph of boats in the old harbor. Surely, I thought, the photograph I had taken the previous night of the pink sunset over the harbor in Komiža was more beautiful than the seemingly hastily composed postcard image of the same scene.

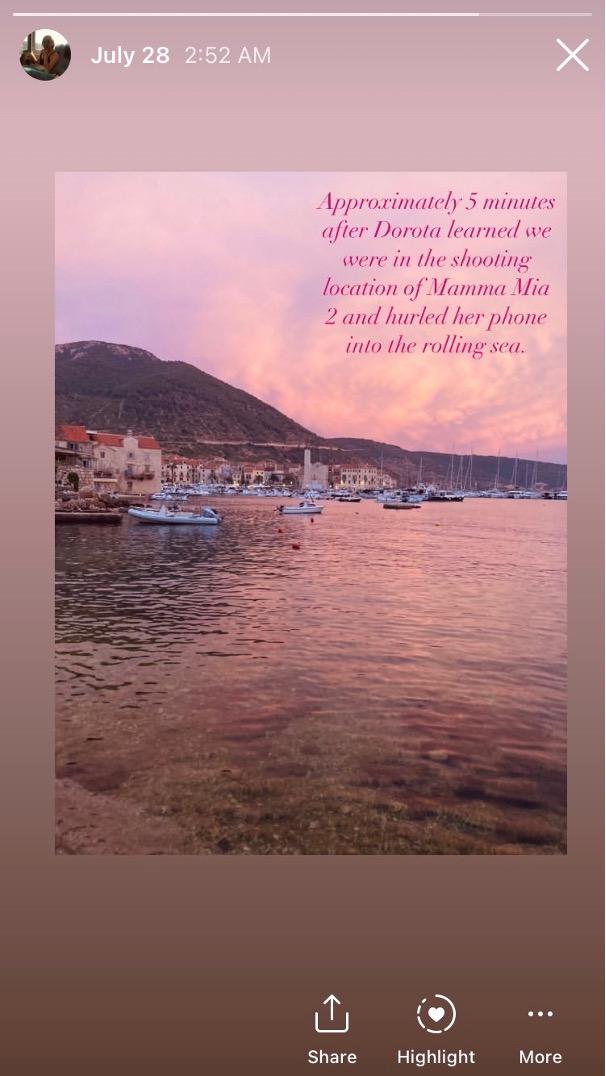

Later, I posted my pink sunset to Instagram Stories with a humorous caption. The act fulfilled the historic function of the postcard—to swiftly and cheaply share an illustrated message.

Seen by over 100 people over the next 24 hours, the story represented the efficiency of current communication technology, as well as its transformation. While a postcard usually travels to one specially selected destination, my Instagram traveled around the globe to be shared, but not saved, both by people I hardly knew and my dearest friends.

Still, before I left the island, I dutifully slid two postcards I’d purchased—one of the aforementioned harbor and the other a vintage photograph of the town square—into the mailbox at the bus station. I can’t say this was an efficient way to deliver my messages: It took about a month for the postcards to reach their recipients. In the interim, I called, visited, and sent dozens of texts. But I sent them to express gratitude and love in a slower, indeed snail-like, mode of communication.

Postcards were an instant sensation when they first appeared in the late 1860s. By the year 1900, 90 million postcards were in circulation in Russia; 1 billion traveled through German post offices in 1903. Historian Lydia Pyne posits that they served as a precursor to today’s fast and free forms of communication, setting the expectation that one should be able to send a message with speed for little money.

This success surprised early critics. Unlike the letter, the postcard did not conceal its message from prying eyes with an envelope. Its fusion of text and image, however, was a hit with consumers. The postcard became the souvenir par excellence of the 19th and 20th centuries, coinciding with the rise of leisure tourism. Addressing you directly and personally, the postcard brought faraway places into your home and allowed you to hold them in your hands.

Because of this, the most obvious association of the postcard has always been travel. But its connection to place isn’t neutral.

Artist Zoe Leonard’s installation You see I am here after all (2008), which displays several thousand vintage postcards of Niagara Falls, opens up a dialogue about what souvenirs, like the postcard, memorialize.

Indeed, standing before Leonard’s monumental work myself, I wondered, what exactly does she suggest is still “here after all”?

Perhaps she is referring to the connections that the medium preserves. Or to the power of a place like Niagara Falls, which asserts its presence, despite being fragmented into an uncountable number of tiny cards and distributed around the globe. At the same time, perhaps the exact opposite holds true: that the mass-produced image of the falls, reproduced again and again on disposable postcards, might be more enduring and unchanging than the falls themselves, so transformed by the touristic landscape that surrounds them.

Postcards, as Leonard’s project suggests, are not only souvenirs of place, but also—and today, mostly—souvenirs of time.

The nature of that time has shifted since the postcard’s invention. The history of the postcard charts a poignant trajectory of the 20th century: embodying the utopic and futuristic promises of its first decades, it transformed into a relic of a slower and seemingly more stable world of connection by its close.

Now, if we encounter old postcards, they provide a window into past networks, connections, and temporalities.

This was what I had in mind when I made my own series of paintings and drawings about postcards in 2016.

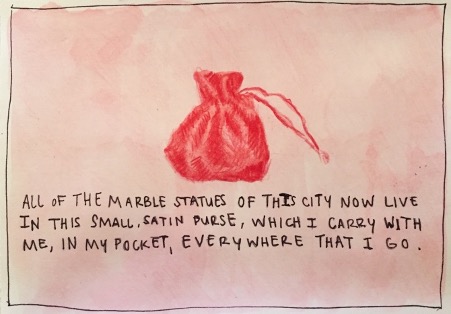

I produced Unsent Postcards in Vienna over the course of a week on blank postcards that I purchased at the art store. I wanted to create souvenirs to preserve my experience of strolling through the city, reflecting on the dissolution of a relationship with increasing lucidity as my thoughts gained clarity against the backdrop of the former Habsburg capital.

It was this intangible process that would be my souvenir, and that I therefore wished to document and give material form. Whereas I typically send postcards to reaffirm relationships, I hoarded these for years. In this way, the unsent postcards represented an ending, as well as the possibility, or threat, of restoring relationships not only to another person but to different versions of events and of the self.

When I explained this project to a friend over drinks in Paris, she worried that it would reek of sentimentality. Postcards are, after all, sticky with nostalgia.

But as cultural theorist Svetlana Boym showed us, there are at least two forms of nostalgia. The type of nostalgia that prioritizes emotional ties over critical thought is what Boym called “restorative nostalgia.” From this perspective, the form of the postcard might reflect a desire to recreate an idealized world that no longer exists (and perhaps never did).

But the postcard can also correspond to “reflective nostalgia,” which focuses on the longing for a time that cannot be resurrected. In contrast to restorative nostalgia, which is at the heart of today’s powerful, nationalist ideologies, reflective nostalgia brings the past into the present in order to critically engage with the relationship between the two.

At least initially, my postcards considered a personal catastrophe. Ultimately, however, Unsent Postcards helped me to consider the potential power and shortcomings of nostalgic gestures, particularly in moments of crisis. Because just as restorative nostalgia can trap us, reflective nostalgia can also provide an antidote to the claustrophobia of conventional, unrelenting, and irreversible linear time by allowing us to travel into alternative temporalities.

The ways we imagine and long for the past shape possibilities for the future. That’s why engaging with this seemingly obsolete technology might encourage us to look beyond a narrative of newness to the unrealized possibilities in the past. It might likewise allow us to examine and expose the uncritical longing for an idealized past that pervades our political world today.

The beauty of the postcard is that it invites us to ruminate on those alternative possibilities, share them, and hold them in our hands—all for little more than the price of a postage stamp.

Send A Letter To the Editors