Tim Birkhead, one of the world’s leading bird biologists, shares why being open to learning from people outside of academia’s ivory tower—in this case hobbyist birdkeepers—can lead to “unexpected and exciting results.” Photo by T.R. Birkhead.

Birdkeepers are almost universally scorned by anyone else interested in birds. Biologists and birdwatchers alike are generally opposed to the idea of birds being kept in captivity. But during a lifetime of admiring and studying birds, birdkeepers have helped me push the field forward and taught me something along the way: Sometimes seemingly irreconcilable worlds can collide, with wonderful results.

Some estimates suggest that during the 19th century, every second household in Britain raised “cage birds.” In an era before radio, TV, or social media, the creatures provided company, entertainment, and occasionally education. The European goldfinch was the most popular: easily tamed, beautifully colored, and with a tinkling, spirit-raising song.

In the 1950s, when I was growing up in northern England, many people—usually men—still kept birds. They bred and raised their birds, as well as entered them in competitions and exhibited them at shows in hopes of winning awards.

For someone keen to get close to birds, as I was as a kid, it was natural to want to keep birds, too. My father encouraged me by building an aviary in the garden. Looking after my birds made me generate a tremendous sense of empathy for them. When they successfully nested and reared their chicks, I was a proud parent. I felt the same about wild birds—a sense of wanting to care for them—especially during the pesticide era of the late 1960s, when many died from DDT exposure. I became obsessed. I studied zoology as an undergraduate, and then undertook a doctorate on birds at Oxford.

By the 1970s, when I did my Ph.D., most people who still kept birds in Britain were working class. Among the wealthier set concerned with conservation, including some of the people with whom I studied, keeping birds in confinement was considered unethical.

At the time, my field of study was undergoing a revolution. We were beginning to look at behavior through an evolutionary lens, and to ask new questions. Why, for example, did some animals pair monogamously while others were promiscuous? With this new approach, formerly inexplicable behaviors and anatomical features started to make sense.

My work focused on bird reproduction, a subject of interest for evolutionary biologists, but also for birdkeepers. When a group of the hobbyists invited me to make a visit and tell them about my research, I willingly agreed.

The meeting was in a pub in a deprived, and to me scary, part of town. Everyone ignored me until they had consumed a couple pints of beer. We then walked upstairs, where my talk was to take place. There was no introduction—just a long pause followed an irritated voice from back shouting, “Well, go on then!”

I started talking, but the atmosphere was like ice, with everyone leaning back on their chairs as though to keep as far away from me as possible. I’d never felt such hostility. After 30 minutes there was a break for more beer and sausage rolls. I decided to abandon my planned talk. In the second half of the meeting, I instead focused on one aspect of my research, a topic known as “sperm competition” in birds.

Zoology’s new evolutionary approach had also transformed our thinking about sexual selection. Before, for example, biologists had assumed that female animals were sexually monogamous. When they observed a bird copulating promiscuously, they considered it an aberration of no biological significance. But with our new evolutionary spectacles, we saw that such behavior might increase an individual’s success — it would enable it to leave more descendants and more copies of its genes.

And it wasn’t just promiscuity that enhanced an individual’s breeding success. Other traits also increased a male’s chances of fertilizing a female’s eggs—including the size of his testes. Bigger testes mean more sperm, and more sperm mean more lottery tickets in the competition to fertilize a female’s eggs after she has mated with more than one male.

My audience knew all about promiscuity, of course—but not in birds. Now they listened in amazement, leaning forward, eager to discover the seedier side of avian life. The questions came thick and fast at the end of the talk. With a huge sense of relief, I realized I’d made a connection.

Then, as I prepared to leave the meeting, a man came up to me. He told me that he bred bullfinches. He thought their biology might differ from the birds I had discussed in my talk.

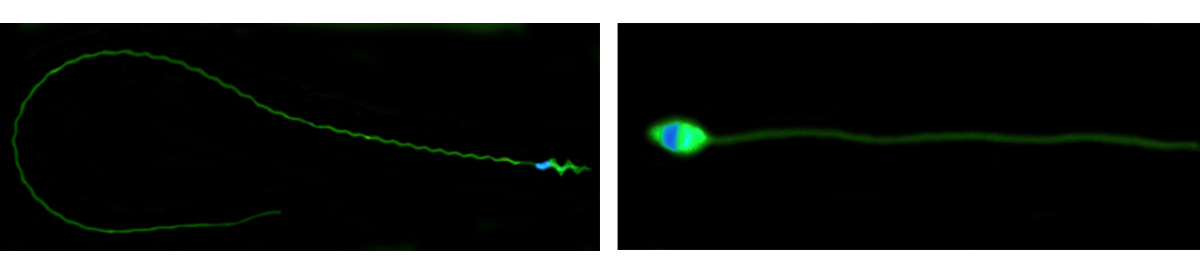

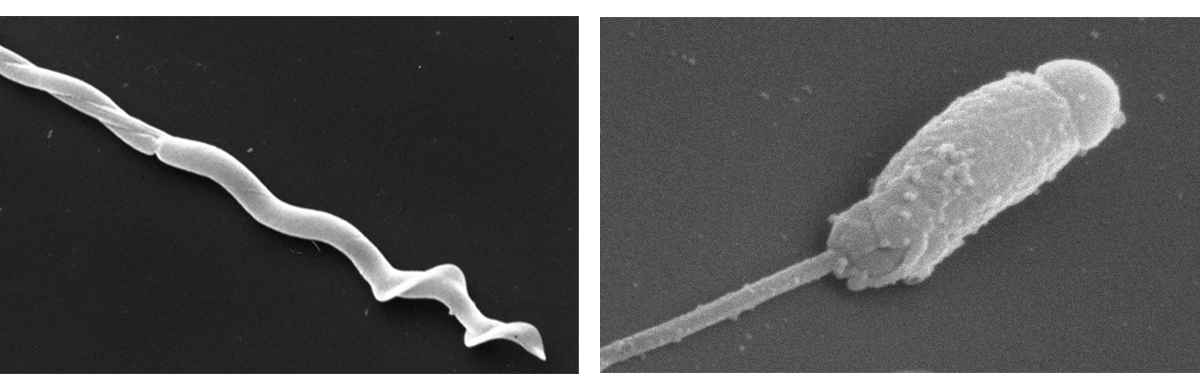

Note the differences of sperm morphology—the size and shape of sperm—with the greenfinch sperm (left) and the bullfinch sperm (right).

The males of many small birds, such as robins and finches, have a structure called a cloacal protuberance during the breeding season, which houses the male’s sperm store. Species whose males have large testes also have large cloacal protuberances.

The bullfinch, he said, had no cloacal protuberance. I was taken aback. I had examined dozens of species and never found one with no cloacal protuberance at all. No one else had reported such a finding, either. How could this birdkeeper had noticed something no scientific ornithologist had seen?

I visited the birdkeeper and left with the body of a male bullfinch that had recently died, which the man had kept in his freezer. I took the bird to the university, thawed it out, and dissected it. To my amazement, the bird’s testes were tiny, despite the bird being in prime breeding condition. And sure enough, it had no cloacal protuberance.

With a bit more dissection, I found the bullfinch’s sperm. To my astonishment, they were smaller and simpler than those of any other finch I had ever examined. I began to feel like I had struck gold.

A close-up view of a house sparrow sperm with a helical head (left) and a bullfinch sperm head with a round shape (right).

My bullfinch dissection suggested that male birds’ reproductive organs adapt depending on the likelihood that their partner will be unfaithful. There was already plenty of evidence for male adaptation associated with high risks of female promiscuity—large testes in randier species—but here was evidence it could work the other way too. If a female wasn’t going to play the field, a male didn’t need to waste energy growing bigger testes or producing more sperm.

There was one more discovery from the dissected bullfinch: its sperm was an unusual mix of good and bad: some were perfectly formed, but many had broken tails, deformed heads, or two tails, and were incapable of fertilizing an egg. Why so many hopeless sperm? I conjectured that “quality control” was another thing the monogamous male bullfinch could do without.

With the help of birdkeepers, I began to test my hypotheses. I examined large numbers of male finches during the breeding season, checking the size of their cloacal protuberance and examining their sperm (conveniently shed when the bird pooped, and therefore easily and harmlessly collected).

As I looked at a range of other bird species, a clear pattern emerged: The quality of the sperm a male bird produced correlated with the amount of competition he faced. The bullfinch was humbly endowed—with tiny testes, tiny sperm, and a high proportion of badly made sperm—because he was strictly monogamous. But more promiscuous species like the dunnock—a common bird in English gardens whose females sometimes keep two husbands—were the opposite. The males have huge testes, a very large protuberance, and produce super sleek, high-quality spermatozoa.

All of this discovery came out of one casual conversation outside academia’s ivory tower. The bird breeders helped me obtain samples that would have otherwise been very difficult to get, and by involving them in our evolutionary research, their horizons were broadened too.

People engage with birds in many different ways. We underestimate the knowledge bird breeders have, simply because they are not part of mainstream birding culture. Intellectual snobbery is the enemy of discovery. Being open to the ideas of others, especially amateurs, can, as I discovered, lead to unexpected and exciting results.

Send A Letter To the Editors