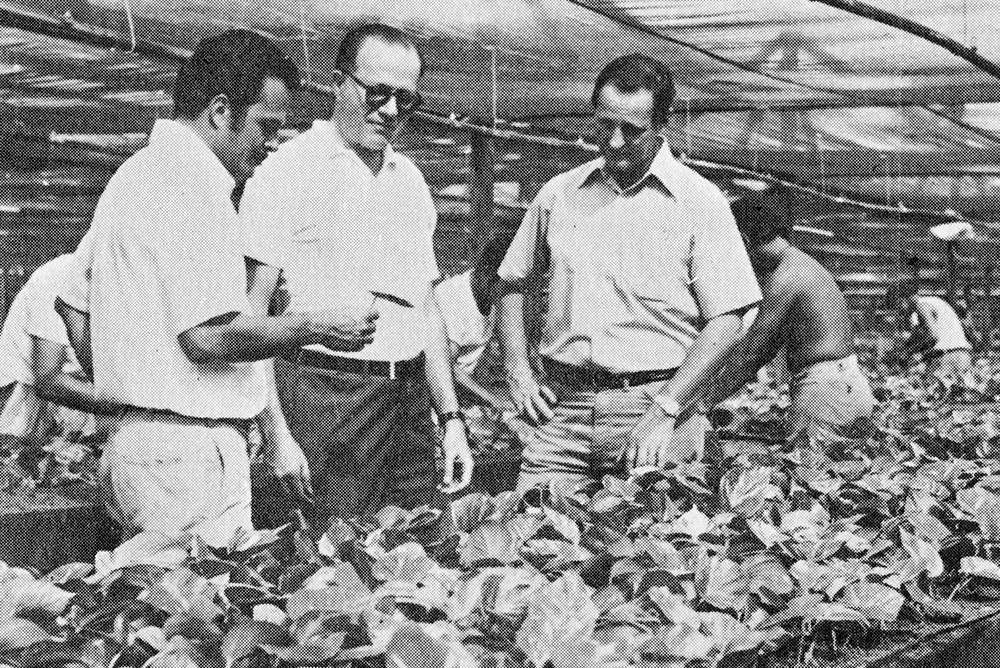

CEO Eli Black (middle) allied United Fruit with good causes, believing it would be good for business. The strategy worked, for a time. Historian Matt Garcia explains. Courtesy of author.

After the latest banking crisis, an old question has resurfaced: What should corporate executives care about, people or profits?

Hard-right Republicans contend that it was “woke” investment strategies of liberal executives—who cared about the “ESG” (Environmental, Social, and Governance) credentials of target companies—that led to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. Their position harkens to a 1970 doctrine of Chicago School economist Milton Friedman, who chastised proponents of “social responsibility” in corporate management for “preaching pure and unadulterated socialism.” He famously advised CEOs to scrap high-minded attempts to improve the world through business and return to their primary goal of increasing profits for their shareholders.

A worthy target for Friedman might have included the enigmatic businessman, Eli M. Black.

In that same year, 1970, Black, a former rabbi, became the new “banana king” when he acquired the hemisphere’s most notorious food company, United Fruit, known as “el pulpo” (the octopus) for its invasive business practices across Latin America.

Black saw value in United Fruit’s famous brand, “Chiquita,” and embraced the opportunity to associate it with good causes, including the humane treatment of farm workers. As he wrote soon after acquiring United Fruit, “Socially conscious programs, designed to improve the quality of living of employees, are indeed the legitimate concern of business.” United Fruit’s business included Inter Harvest, which produced lettuce in California, where Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers had just scored a significant victory by signing contracts with grape growers after five years of protest.

Black’s first act as CEO signaled a rejection of Friedman’s doctrine. At Inter Harvest, he went against fellow growers and the advice of his executive team by signing contracts with the United Farm Workers. Black chose this course to avoid a boycott of his “Chiquita” bananas but also to work with Chavez, whom he regarded as a potential business partner. Both men believed that a conscientious public, now aware of the exploitation of farm workers, would choose Chiquita brand lettuce carrying the union’s black eagle label over competitors that did not. In time, the CEO came to see Chavez as a friend. Black invited the labor leader to private Passover seders at his home in Westport, Connecticut, and business conferences at Harvard University.

Black doubled down on his strategy of “social responsibility” in his remaking of United Fruit in Honduras, where the company was the country’s largest employer. There, he collaborated with Oscar Gale Varela, the venerable leader of the banana workers union, SITRATERCO.

Gale had survived corrupt dictators and the manipulation of the Honduran labor movement by the CIA and the AFL-CIO to forge one of the most powerful unions in Latin America. The U.S. State Department privately remarked that Gale’s movement was “five times the size of the armed forces and 10 times more than the total number of university students.” The American government regarded him as “the conscience of the nation” and treated him as such, affording Gale protection whenever he challenged the authority of general Oswaldo López Arellano who had seized the presidency in coups d’etat twice during the 1960s and 1970s.

For Black, Gale kept labor unrest at bay and state corruption in check. Black rewarded Gale and SITRATERCO with the most generous wages and benefits for farm workers in Latin America. He honored Gale’s request to abandon piece-rate compensation for banana workers by adopting a set salary based on a 44-hour work week. Black also made significant investments in the schools and hospitals used by workers, replaced U.S. employees with Hondurans, and added 10 paid vacation days per year.

Skeptical journalists came to Honduras in 1972 to confirm this transformation. Several left convinced, one writing that Black’s new United Fruit “may well be the most socially conscious American company in the hemisphere.” A contented Gale told the New York Times, “The company respects us and we respect the company.”

So, why don’t we remember Black as a paragon of virtue, and his management of United Fruit as a notable counter to Friedman’s doctrine? The easy answer is that Eli Black’s adventures in social responsibility ended tragically.

In California, Cesar Chavez never delivered on his promise to improve the hiring process for farm workers, leading to poor quality and the company’s eventual abandonment of the Chiquita label for California lettuce.

In Honduras, Gale suffered a stroke just as Arellano agreed to honor Gale’s request for peasant land reform in exchange for accepting the dictator’s unconstitutional third term in office. When the oil crisis hit in the fall of 1973, Arellano used his unfettered authority to impose a tariff on bananas. An embattled Black, losing millions of dollars in transport costs, agreed to pay a bribe to Arellano in exchange for reducing the new tax. When the illicit affair became known to rivals within the United Fruit office, Black struggled to maintain his image but to no avail.

On February 3, 1975, he committed suicide by jumping from the 44th floor of the Pan Am (now Met Life) building in midtown Manhattan.

Black’s dramatic end may suggest to some that Milton Friedman had been correct. But, in retrospect, there was little Black could have done to make United Fruit profitable. And, if anything, it was Black’s partial adoption of Friedman’s advice that did him in.

Feeling pressure from dissatisfied shareholders in 1973, Black pursued a legal, but at the time frowned-upon stock buyback scheme—refinancing debt by purchasing existing securities with cash reserves—that temporarily raised the value of United Brands’ shares. The business press that had previously lauded him prior now turned on him, alleging that he deceived the public by creating an illusion of profitability. Forbes called the move a “fiscal fairy tale” and “magic show,” while a noted accounting professor chastised his move as “fiscal masturbation.” Black’s stock buyback halted the abandonment of United Brands by shareholders for a time, but business correspondents and employees questioned whether these funds would have been better spent on modernizing facilities or improving the position of workers.

Sadly, stock buybacks and the never-ending pursuit of higher share values have become the norm on Wall Street since Black’s demise. Black found a loophole in federal law to execute his deal. By 1982, no such trickery was necessary; President Ronald Reagan encouraged the Securities and Exchange Commission to make buybacks legal for all companies. As David Gelles shows in The Man Who Broke Capitalism, former G.E. CEO Jack Welch engaged in the largest stock buyback program in American history, enriching himself and investors, while denying the firm critical funds for research and development, and sacrificing the job security of loyal workers. Ultimately, Welch’s management system–very much in the tradition prescribed by Friedman–eroded the foundation of one of the most respected U.S. companies of the 20th century.

The pursuit of stock value over all other considerations is stealing the future from companies and destroying the foundation of the American capitalist system that many critics of the current bank crisis claim to be defending. Such critics have resisted policies such as an excise tax of 4% on profits from stock buybacks that strive to keep funds invested in research and development and prevent the squirreling away of wealth into bank accounts of people who have done the least to create it.

Ultimately, they ignore what Eli Black, in his best moments, understood: A company’s value is as much a product of its employees’ hard work as the CEO’s business genius.

Send A Letter To the Editors