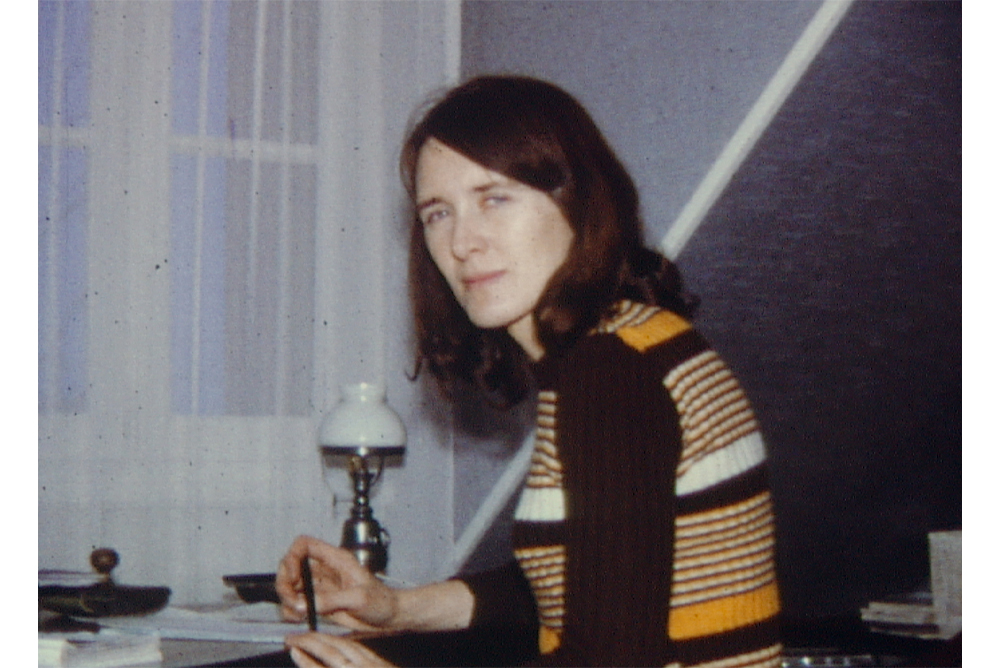

Writer Tom White considers Nobel laureate Annie Ernaux, her book The Years, her film The Super 8 Years, and her singular take on memory—personal and collective. Still from “The Super 8 Years” (2022). Courtesy of Kino Lorber.

Memory is an imperfect reflector of lived experience. We look back through a series of lenses, and our focal mechanisms shift with the light. Personal memory is shape-shifted by history—what is reported on, ruminated on, analyzed, assessed. It’s shaped by who we meet, what we see, and who we choose to see—and who chooses to see, or not see, us. Memory refracts experiences, processes and purees them.

What does the tension between memory and history—both personal and shared, the “I” and the “we”—teach us about both remembering and documenting our time spent? How do we view and engage with the past? Are memory and experience and memory and context intertwined? And how might we reconcile these?

Annie Ernaux, the France-based 2022 Nobel laureate for literature, earned fame and renown as a writer who is deeply entrenched in the power of memory—as a repository of lived experiences, as a cistern of hope and hearth, as an existential paradigm. When announcing the honor last fall, the Nobel Committee cited “the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory.” Her masterpiece The Years, from 2008, recounts her own history and that of post-World War II France, and explores how the two narratives intertwined and diverged.

The Super 8 Years, an essay film she made with her son David Ernaux-Briot, premiered at the New York Film Festival days before she was anointed the 2022 Nobel laureate. The Super 8 Years spans the 1970s and early 1980s and might be construed as a cinematic investigation into that period through home movies. The Years covers those decades within its exploration from 1941 to 2006.

Watching The Super 8 Years in tandem with The Years gave me a deeper insight into both works—and into Ernaux’s sensibility. Ernaux’s two works together, by overlaying images on her literary self-examinations, allow her to construct both a remembrance of things past and a reconstruction and reconsideration of their remembrance, resulting in, to this reader/viewer, a diptych-esque response to Proust’s masterpiece.

The Years is a reconciliation with the history of France as Ernaux lived it, observed it, and processed it—from her point of entry during World War II through the waning days of colonialism; from the presidential administration of Charles de Gaulle to that of Jacques Chirac; during teetering toward and away from socialism; amid persistent undercurrents of classism and racism.

Ernaux is ambivalent about herself; she refers to herself as “we,” rather than “I,” sublimating a part of herself and blending in with the collective. Hers is a foot soldier’s view of history, and a quest to find one’s role and assert one’s place within it.

The Years approaches memory as a fluid force. In a section that takes us to 1953 and 1954, for example, Ernaux lists:

-the great train strike of the summer of ’53

-the fall of Dien Bien Phu

-Stalin’s death announced on the radio, one cold morning, in March, just before children left for school

and juxtaposes these moments in world history with her own childhood memories, some idyllic:

-the Tour de France passing through her town

-embroidering a napkin ring

some bittersweet:

-reading the summaries of films she will not see and books she will not read

and some harrowing:

-The scene between her parents … when her father tried to kill her mother, dragging her to the cellar … where they kept the sickle planted.

In a way, The Years and Ernaux’s writing of it are acts of alchemy—making the past present and the present past, morphing them together with an artist’s light, illuminating the crevices, brightening the corners. It is not that she’s completely oblivious to the world as it turns; it’s that she is a work in progress—observing and engaging that parallel evolution, while reckoning her own. They are mirror and window.

It makes sense, then, that The Super 8 Years picks up so deftly where the book leaves off. Ernaux and Ernaux-Briot stitched the film together using home movies chronicling family life: vacations, and the mundanities of middle class and middle age in 1970s and 1980s France. The movies are grainy, and they are silent.

Ernaux adds the music, environmental effects, and narration—again, using “she/her” and “we/us,” as if the Annie she beholds on celluloid is a doppelganger, filmed against her will. Philippe, her then-husband, documented the family’s domestic life and its attendant milestones such as birthday parties and holiday gatherings, as well as vacations to Morocco, pre-Pinochet Chile, Albania, Egypt, Spain, and the Soviet Union, among others. Fifty years later, Ernaux, as narrator, assesses her engagement with those places in Cold War history in the past—both as vacation destinations and as validations of her progressive leanings—and from her present perspective, where she questions her place in a postcolonial, vastly changed landscape.

Philippe operates the camera at all times. He is the scenarist, auteur, director, producer, cinematographer. Annie is the unwitting protagonist—mildly annoyed, always self-conscious. It’s an engagement that perhaps betrays the fragile state of their marriage. He would later leave the footage with her, and take the camera with him.

When one engages the home movies as sui generis, Annie is the subject, frozen in a moment in time when she was vulnerable to Philippe’s camera. Her truth lingered beyond the frame. But fortified by her discerning narration 50 years later, The Super 8 Years is a reclamation process—a sort of rescue by interrogation and recontextualization. Ernaux the narrator and future Nobel laureate considers her cinematic self, whose career as an eventual literary icon is in its nascent stages, as defined by a patriarchal apparatus. On film, she is a homemaker, wife, and mother, navigating her way through the trappings of womanhood.

These are images of an irretrievable past, of a context that no longer exists, within a disintegrating marriage. As in The Years, Ernaux is probing memories, of her narrative and of “our” broader history.

Ernaux’s memory of her experiences, these chapters in her life, do not always match what she beholds in the footage. The act of remembering and remembrance is an act of editing and subconscious omission, brought to fruition in film. It is also an affirmation of self. Ernaux has in the end reconciled history and memory, collectively and individually. She, as “we,” is the author, the writer, the scribe, the narrator/filmmaker. She, as “she,” in the photos and footage, is preserved in a past moment, yet beckoning the future self for a dialogue. “She” is past and everlasting, unrevivable, yet resurrected.

As the artist, Ernaux is an alchemist, a preservationist, a reanimator of a world that is just memory and history. She may not have answers to what the footage provides, to what the past beckons, but she has questions—for herself, for history, for us. And she leaves it up to us—the sum total of our personal narratives, our fictionalization of them, our collective history and our relations to and reconciliation with the filmed, written, and recorded records.

Send A Letter To the Editors