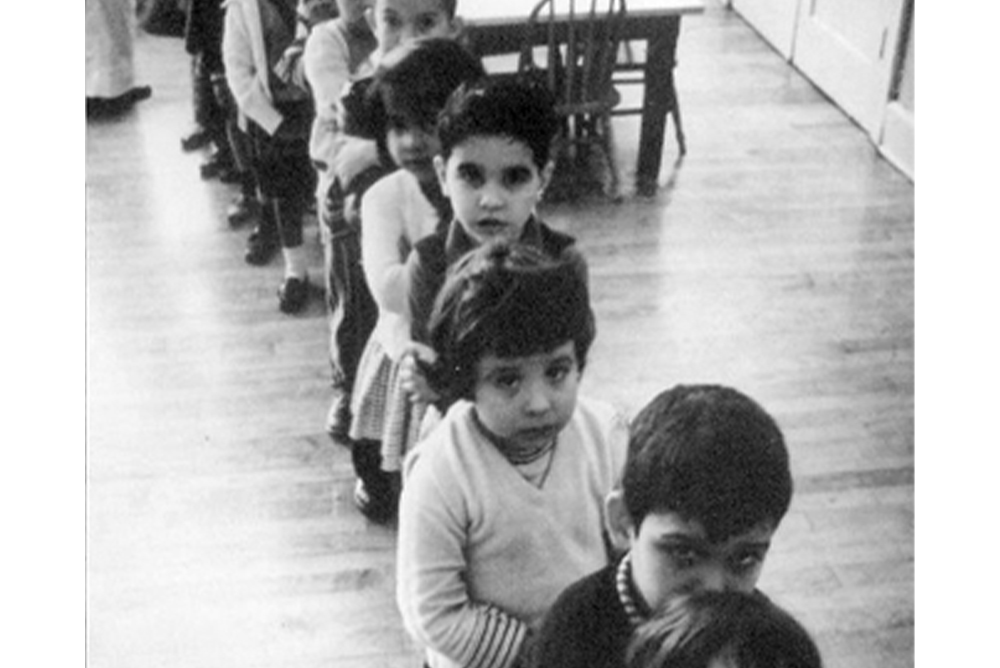

During the 1960s, over 14,000 Cuban children were resettled in the United States. Historian John A. Gronbeck-Tedesco recounts America’s forgotten history of welcoming child migrants. Image of Cuban children lining up to emigrate. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

When Fidel Castro took over Cuba in 1959, 13-year-old José Azel joined the ranks of the underground opposition engaging in acts of sabotage. When Castro closed the country’s schools, José’s father became worried. So he sent his teenage boy on a brief trip to West Palm Beach in June 1961 on a cargo ship full of seminarians. It was the last time they saw each other.

From 2021 to June 2023, U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported just over 400,000 “encounters” with unaccompanied children. The quality of care for these kids has been dubious at best and abusive at worst. Today’s numbers may be unprecedented, but this group is not—in fact, they are part of a long tradition of young people finding refuge in the U.S. without their parents.

In the early 1960s, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare created the Unaccompanied Cuban Children’s Program to care for thousands of minors fleeing their country after its 1959 revolution. Colloquially, it was known as Operation Pedro Pan—a reference to the tale about the boy who could fly. Like today, in the 1960s a vocal contingent of naysayers balked at the newcomers: Some feared that there could be communists in the unvetted masses, while others asked why taxpayers should shoulder their financial weight. Yet drowning out these doubtful voices was a larger willingness to accept the children and to affirm the country’s tradition of sanctuary and freedom in doing so.

The more than 14,000 Cuban minors who arrived to the U.S. between 1959 and 1962—then the largest group of unaccompanied children in U.S. history—were among the 250,000 Cubans who trekked across the Florida Straits during that period. In contrast to today’s migrants, the Cubans were cast as refugees and symbols of anticommunist heroism. President John F. Kennedy reminded the country that welcoming refugees was a Cold War imperative. In a letter to Congress, Kennedy heralded the U.S. as “a refuge for the oppressed” with a “long humanitarian tradition of helping those who are forced to flee to maintain their lives as individual, self-sufficient human beings in freedom, self-respect, dignity, and health.”

The Children’s Program resettled young people across the nation in group homes and with foster families throughout the country—from Helena, Montana, to San Antonio, Texas, to Dubuque, Iowa—largely paid for by state and federal coffers. At times, parents did not know where their children had been relocated.

The program relied on a vast network of federal and state offices and a long list of nonprofit church groups, child welfare agencies, and Pan American and KLM airlines, which would help procure seats for these children, as well as embassies, parochial schools, and a counterrevolutionary network in both nations. Those without immediate family support in the United States—more than 8,300 children—received care through the Catholic Welfare Bureau and other religious, governmental, and non-governmental organizations.

Some Pedro Pans found respite with Protestant, Jewish, and secular organizations, but the nucleus of the program was the Catholic Church, which assumed responsibility for 7,346 Cuban children. At the program’s helm was Bryan O. Walsh, an Irish priest who’d recently relocated to Miami, and embraced his mission with gusto. Walsh later called his role in Operation Pedro Pan “an opportunity given to me by Divine Providence to combat communism.” He had ample support from the Church, which also opened its doors to Catholic leaders isolated and banished by the Cuban government.

After arriving in the U.S. with a group of Catholic seminarians, José Azel jumped into the world of American adolescence. The transition was connected to the automobile, and he remembers the immense glee he felt registering for a driving permit. Football, rock ‘n’ roll, and an occasional cigarette rounded out the adaptation process for the young man.

Other Pedro Pans tell similar bittersweet stories of their crossings. Mayda Riopedre was a 15-year-old student at American Dominican Academy in Havana when she arrived in Miami. Mayda had lived a privileged and “very American” life in Cuba— she took classes in English and U.S. history, listened to American shows on the radio, took ballet and piano lessons, and had a French tutor.

After spending a month in a transitional shelter, Mayda Riopedre and her sister spent a month at St. Mary’s Home in Dubuque, Iowa, where they went bowling for the first time, before being sent to live with a family in Signal Mountain, Tennessee. She retains some very pleasant memories of her time there, but she also recalls a favorite outdoor spot where she would look at the mountains and cry inconsolably. The sisters and their parents reunited two years later, and today Mayda considers herself “lucky” and will be “forever grateful” for the foster family.

Why did so many parents choose to send their children away? The upheaval of the revolution—including school closures and new revolutionary pedagogy, nationalized property, and rumors that Castro’s government would dispossess parents of their children—was frightening enough to make the decision feel warranted for many Cuban families.

They also believed that the separation—and Castro’s reign—would be brief. But most Pedro Pans did not see their parents for months or even years —and in rare cases, like José Azel’s, ever again.

Now in their 60s and 70s, the former Pedro Pans—many of whom are part of Florida’s large Cuban community—find themselves ensconced in the vitriol surrounding today’s migrant children. Unlike the majority of Pedro Pans, who lived comfortable lives in Cuba, these young people come from locales ravaged by violence and economic scarcity.

And they are receiving a very different welcome. In 2019, 3,000 children were housed at a center in Homestead, Florida, five miles from the Florida City camp that had sheltered hundreds if not thousands of Pedro Pans. Then the Trump administration closed it, which drew criticism from those who argued that the state should provide suitable accommodation for children, as it had done 60 years prior with the Cuban Children’s Program.

More recently, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis bickered with the Miami Archdiocese after he issued an executive order that curtailed the ability of Florida agencies to care for undocumented migrants, including children. Pedro Pans took sides: Some argued in favor of sheltering the minors while others sided with DeSantis and drew differences between today’s young migrants and the Cold War context of their own crossings.

As their hesitancy indicates, today many Americans are reluctant to support similar groups in need. The country took in just 11,411 refugees in the 2021 fiscal year, the lowest number since 1980. UNICEF estimates that a record 43.3 million children live in forced displacement worldwide. Those crossing the U.S. border often remain invisible or banished to the status of a national crisis rather than an opportunity to provide help. But the Pedro Pans, aided by government assistance and everyday American altruism, exemplify what is achievable when we harness our abundant resources and guarantee our healthy tradition of refuge for the world’s most vulnerable populations.

Send A Letter To the Editors